The following notes on Raging Bull were written by Garrett Strpko, PhD student in the department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A restored 4K DCP of Raging Bull will screen on Saturday, December 9 at 7 p.m. in the Cinematheque's regular screening venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Garret Strpko

Raging Bull is often remembered today as the swan song of the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s. Noted film critic Peter Biskind invokes it as a sort of bookend in the title of his definitive written history on the period, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Indeed, the film is a prime example of the type of actor-driven project that is difficult to imagine getting produced in quite the same way today. “Although Raging Bull was later selected in a Premiere magazine poll as the best movie of the ‘80s,” Biskind writes, “it was very much a movie of the ‘70s.” While his peers of the “movie brat” generation such as George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were busy helming the kind of high-concept, high-budget, and high-return films which define the industry still to this day, Scorsese once again turned to a personal, upsetting, and moving portrait of damaged and damaging American masculinity.

Scorsese, however, was not the originator of the project now discussed as one of his greatest. Raging Bull is based on the memoir of Jake LaMotta, a boxer active in the 1940s and 50s known for his ability to withstand beatings and take punches to wear out his opponents. Robert De Niro read LaMotta’s memoir while filming The Godfather: Part II and developed a strong interest in the character. He immediately pursued translating the book to film. De Niro first approached Scorsese about directing the film on the set of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), although it took some time before he came to share De Niro’s enthusiasm. He initially passed on the film on the grounds that he had little interest in boxing, let alone sports in general. As Biskind puts it, “Besides, LaMotta wasn’t much of a boxer. His singular talent lay in his ability to absorb punishment.” Eventually, however, De Niro brought the project to producer Irwin Winkler, who, riding high on the recent success of the boxing film Rocky (1976), agreed to produce the film if Scorsese could be attached to direct.

This did little to pique his interest. Scorsese was undergoing one of the darkest personal and professional periods of his life. His most recent film New York, New York (1977), a tribute to classical Hollywood musicals starring Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli, was received poorly both among critics and at the box office—his first major failure. To cope, he dove deeper into his increasingly debilitating drug habit. Creatively frustrated and personally dissatisfied, Scorsese put off working on the film, handing it off to frequent collaborator Mardik Martin, a co-writer on Mean Streets (1973) and New York, New York, to develop a first draft of the screenplay. Scorsese and De Niro struggled with Martin’s initial script. Both sought to bring in a more personal angle on La Motta’s story, and so enlisted another collaborator, Paul Schrader, screenwriter of Taxi Driver (1976), to perform some significant rewrites.

Schrader’s reworking of the script found the angle that De Niro and Scorsese were looking for. Rather than focusing solely on Jake’s story, Schrader’s rewrite oriented the story around the relationship Jake and his brother/manager Joey. Drawing on his own troubled relationship with his brother and sometime-collaborator Leonard, Schrader imbues the film not only with a personal factor, but with a sense of the gloomy edginess for which he is known (indeed, the filmmakers speculated that the film as written in Schrader’s rewrite would be rated X).

Meanwhile, Scorsese’s health only continued to decline. In Fall 1978, after returning from the Telluride Film Festival, he was rushed to the hospital hemorrhaging and severely underweight, with a potent mix of prescription and recreational drugs coursing through his veins. A doctor informed him he was in danger of dying any moment. With intense treatment and the support of his close friends, including De Niro, he finally came back around with a full sense of purpose for Raging Bull. Scorsese now saw that LaMotta’s story, like his own, was one of self-destruction, its effects on oneself and the people one loves. Scorsese emerged from his near-death experience determined and reinvigorated. He had finally found the personal angle that would make the film meaningful for him to make.

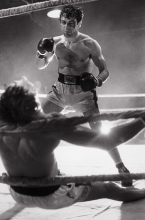

Raging Bull began shooting in 1979. The filmmakers cast two relative newcomers in career-making roles: Cathy Moriarty, in her film debut, as Jake’s wife Vickie and eventual Scorsese mainstay Joe Pesci as his brother Joey. Typical of his method style of acting, De Niro prepared for the lead role by immersing himself in the boxing world, even participating in three fights in New York, with the real-life Jake LaMotta serving as his trainer. For the bookend scenes set in the 1960s, De Niro gained nearly seventy pounds to play LaMotta in his period as a washed-up nightclub performer. Shot by cinematographer Michael Chapman and edited by Scorsese’s longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker, the film’s boxing sequences remain some of the most impactful and commented-upon of Scorsese’s career, including the surreal and now-iconic fight against Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes). His distinctive approach to camera movement, editing, and sound design communicates the impact of each jab, hook, and uppercut. Easily the most striking stylistic feature of the film, however, is its arresting use of black and white photography, a creative choice which Scorsese made, among other reasons, to give the film a ‘tabloid’ feel.

The film was released by United Artists in late 1980. It was initially met with low box-office returns and mixed reviews, but it performed well at the 53rd Academy Awards, where it was nominated for eight Oscars and won two, Best Editing and Best Actor for Robert De Niro. The actor’s intense and uncompromising interest in the character of Jake LaMotta paid off with prestige. Furthermore, the film is regarded by many as the finest of Scorsese’s career. A remarkable and devastating portrait of a self-hating narcissist led by a tour de force performance, Raging Bull is a fitting end to a stylistically, narratively, and thematically daring period in American film history.