Listen below to an episode of 70 Movies We Saw in the 70s, featuring co-hosts Ben Reiser (of UW Cinematheque and Wisconsin Film Festival) and Scott Lucas (renowned musician and member of Local H) discuss the marvelous hillbilly horror Race with the Devil. Then see the movie in a new 4K DCP on Friday, July 19, 7 p.m., in the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Free admission!

RACE WITH THE DEVIL on 70 Movies

RACE WITH THE DEVIL: A Trip Gone Bad

These notes on Race with the Devil were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A new 4K DCP of Race with the Devil will screen in our "Action Vehicles" series on Friday, July 19 at 7 p.m. in our regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave.

By Josh Martin

In Susan A. Compo’s biography of Warren Oates, the iconic star of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), she recalls a bizarre story from the production of Race with the Devil, Jack Starrett’s 1975 genre-bender. With Oates and co-star Peter Fonda eager to appear in “a sure-fire moneymaker,” the former agreed to lead the project — tacking on the additional request of having producers furnish him a new RV. Preparing to shoot the film in the Texas winter, Oates loaded up the vehicle with friends, including pal Harry Dean Stanton, for a series of drives through the southwestern United States. During these drives, Oates and his companions took heavy doses of psychedelic drugs. Soon, they reported experiencing close encounters with extraterrestrial life — encounters witnessed only by those under the influence. In Compo’s account, Oates associate Dean Jones recalls that “they all saw a UFO'' on the drive to San Antonio, though Bob Watkins, another friend, acknowledged that they “were hallucinating to some extent.” This countercultural debauchery may seem irrelevant to the eventual production of a major motion picture, but it is in these conditions — an anxious, drug-addled state, blending genuine fear of the unknown and jovial absurdity — that the equally paranoid and unusual Race with the Devil came to exist.

Starrett’s film features an elevator pitch that practically jumps off the page. Four years after Fonda and Oates first appeared together in The Hired Hand (1971), the former’s directorial debut, the duo reunited for a road movie-turned-horror picture about two motorcyclists who stumble upon Satanic rituals deep in the heart of Texas. If this concept seems ripe for campy thrills and witchy kitsch, the tone that the filmmakers strive for proves more sinister, a mood that is immediately evident from the opening credits. As the camera tilts up on the dividing lane of a dark, empty highway, storm clouds gather ahead, clustered around a lone tree as discordant music sets the atmosphere of unease. The clouds change in color to a bright, blood red, with the space eventually abstracted, enveloping the spectator in this frightening universe.

Despite the early preview of a menacing mood, Race with the Devil more accurately simulates the steady deterioration of a bad trip. Fonda and Oates star as Roger and Frank, respectively, two friends and speed enthusiasts who are taking their first much-needed vacation in a long time: a January jaunt to Aspen for some winter skiing. Roger and Frank are joined by their wives, Alice (Loretta Swit) and Kelly (Lara Parker), as they pack into Roger’s brand spanking-new $36,000 motorhome, equipped with all manner of bells and whistles. The RV enables the kind of independence and solitude that the men are looking for, with Roger exclaiming, “We don’t need anything from anybody! We are self-contained, babe.” But more crucially, the road trip gives Roger and Frank an opportunity to relax, to bond with one another, sharing sentimental remarks over drinks and racing their bikes in the Texas desert. Seemingly in an attempt to push the opening credits sequence out of our minds, the film plays up the tranquility of this escape – the sense of calm that washes over our lead characters.

Stopped for the night in an empty valley, Roger and Frank’s boozy soiree is rudely interrupted when a tree is lit on fire several hundred feet from them. Their interest piqued, the buddies look through a pair of binoculars to see a strange ritual, featuring men chanting and wearing bizarre robes. The tone of the film does not immediately shift, with Starrett teasing the potential for comedic hijinks in this peculiar discovery. Yet as the ritual continues, the film initiates an accelerated editing rhythm, with the montage becoming more pronounced in tandem with the demonic chanting. But this is no hallucination: the frenzied cutting culminates in the sacrificial murder of a young woman, an act of violence that sends Roger and Frank into a full-blown freakout. Spotted by the cult, they find themselves on the run, the good vibes of their vacation thwarted.

Race with the Devil plays on the fears of the post-countercultural moment, on a diffuse sense of paranoia directed at the dark side of peace, drugs, and free love. The sheriff, when informed of the ritual murder, grumbles that a “bunch of hippies moved into the area… stuffed garbage up their nose and into their arm,” thus making the town an uglier place. Though Fonda’s Frank is skeptical that the murder is “hippie”-related, the film draws on this constellation of interrelated cultural pressure points, engulfing post-Manson mania, ritual violence, and Satanic panic.

Equally essential to this concoction of mid-1970s anxiety is a fear of rurality, of what horrors may lurk deep within the forgotten, neglected corners of America’s vast landscape. Race with the Devil concocts a disturbing ambience around the denizens of these small Texas towns, transmitting the unshakable feeling that everyone is in on the plot, out to punish the city folks for their invasion on this territory. Compo notes that the screenplay, written by Lee Frost and Wes Bishop, was “inspired” by John Boorman’s 1971 classic Deliverance, another tale of friends who get a little more than they bargained for with some nefarious locals on their vacation. And while the slasher is not a sub-genre in play here, Race similarly recalls Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), particularly in the dusty spaces and open Texas fields where our horror takes place.

Amid this swirl of influences and cultural concerns, the film had a somewhat tumultuous production, which Compo’s book carefully recounts. Co-screenwriter Frost was the original director, but 20th Century Fox became weary of the unpredictable Oates, Fonda, and Bishop’s frequent changes to the dialogue, eventually placing Starrett in the director’s chair as a steadying force. After this change, production settled into a groove, resulting in a profitable endeavor. In one famed anecdote, producer Paul Maslansky solicited the work of “Satanists and black magic experts” as extras, providing a purported verisimilitude to the far-fetched picture.

While writing on Race with the Devil often draws comparisons to Rosemary’s Baby (Polanski, 1968) and The Exorcist (Friedkin, 1973), the particularities of the cult’s Satanic plot here are functionally irrelevant. What Starrett’s film instead offers is a feeling of suspicion — an uncertainty that builds to a surreal sense of entrapment and terror. In this manner, one feels a stronger kinship between Race with the Devil and the uneasy vibes of films like The Wicker Man (Hardy, 1974) or Messiah of Evil (Huyck and Katz, 1973), especially as Starrett’s picture reaches its climax. Though Maslansky believed that the ending “sucked” and co-star Lara Parker lamented its “meanness,” the unsparing, slow-motion conclusion is the perfect validation of the film’s paranoid logic, with all the distressing incidents and unresolved threads coalescing into a nightmarish series of images. Race with the Devil may have its fun — in its intense chase sequences and its buddy film rhythms — but a feeling of inescapable doom lingers once the credits roll.

Cinematalk Podcast: VAGABOND, with Kelley Conway

Winner of the top prize at the 1985 Venice Film Festival, Agnès Varda's Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi) begins with the discovery of the lifeless, frozen body of the young hitch-hiker Mona (Bonnaire). Through flashbacks recounted by individuals who crossed paths with her (portrayed predominantly by amateur actors), Varda constructs a fragmented depiction of this mysterious woman, crafting a mosaic-like portrayal that the director playfully referred to as “Rashomona.” Bonnaire’s multi-faceted turn won her several awards, including France’s Cesar, and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association prize for Best Actress. Vagabond screens on 35mm film as part of our series tribute to David Bordwell at the Cinematheque on Wednesday, July 10. On this episode of Cinematalk, Ben Reiser sits down with Professor Kelley Conway, a noted Varda scholar, to discuss the making-of and legacy of Vagabond.

VANISHING POINT: The Last American Hero

This essay on Vanishing Point is by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A new 4K DCP of Vanishing Point will be screened on Friday, July 12 in the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free. Copies of Vanishing Point Forever by Robert M. Rubin will be on sale before and after the screening. To learn more about the book and the movie, listen to a new episode of our Cinematalk Podcast featuring special guest Robert M. Rubin!

By Josh Martin

Kowalski (Barry Newman), the enigmatic protagonist of Richard C. Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971), is a man of few words. He is stoic and direct, always acting on impulse and instinct. This ethos of simplicity is even reflected in his mononymous title: in a deleted scene with a hitchhiker played by European film star Charlotte Rampling, Kowalski insists that this moniker is his “first, last, and only” name. Suffice to say that Kowalski, who finds himself in an interstate chase with highway patrol officers as he drives from Colorado to California, spends little time explaining the psychological motivations of his actions. Instead, he leaves the mythologizing to Super Soul (Cleavon Little), a blind disc jockey whose program becomes a sort of Greek chorus for the film, narrating Kowalski’s travels by following a police scanner. Through his radio show, the garrulous Super Soul molds the impenetrable Kowalski into a folk legend, a stand-in for the mood of America. Super Soul becomes the voice of Vanishing Point, anointing Kowalski as “the last American hero, to whom speed means freedom of the soul.” “The question is not when he’s gonna stop,” Super Soul wonders aloud, but “who is gonna stop him?”

If this seems rather philosophical for a car chase movie, it all functions harmoniously within Vanishing Point, which is described by cultural critic John Beck “as the apotheosis of the Vietnam-era exploitation/arthouse existentialist road movies produced in the wake of Easy Rider.” Sarafian, who rose in the ranks from industrial films to Hollywood alongside maverick director Robert Altman, indulges in the experimental spirit of the times. Inflected by Michelangelo Antonoini and other European arthouse masters, the film tinkers with temporality, narrative, and ambitious feats of montage, complicating its own straight-forward conceit. With a script written by Cuban novelist Guillermo Infante Cabrera (under the pseudonym Guillermo Cain), the film strives to probe the notion of the American spirit – to shape a portrait of the independent outsider whose resistance to conformity makes him a national icon and source of identification.

Yet far from a singularly intellectual exercise, Vanishing Point uses its sense of formal play to up the ante on its muscular thrills, balancing its competing aims as a State of the Union address and a super-sized stunt showcase. It is this tension – between the melancholic and the thrilling, the thoughtful mood and the high-octane jolts of action – that makes Vanishing Point so distinct. The plot, of course, is simple: late on a Friday night, Kowalski is assigned to deliver a Dodge Challenger to San Francisco. An amphetamine user and a compulsive risk-taker, Kowalski meets his drug dealer prior to the drive and makes a bet that he can complete the drive by 3 PM on Saturday. Such a feat, of course, would require Kowalski to drive extraordinarily fast.

And drive fast he does. In a quote from an interview with Turner Classic Movies that circulated widely upon Sarafian’s passing in 2013, the late director emphasizes his aim to “physicalize speed,” to make this experience palpable for the spectator throughout Vanishing Point. In the film’s initial chase sequence – which commences when Kowalski is spotted speeding by patrol officers – Sarafian initiates a bombardment of aggressive formal techniques. As Kowalski zips through this windy terrain, the camera presents hazy close-ups of the Challenger that soon shift out of focus, drifting into a blur of indistinguishable movement. The scene proceeds almost as a premonition of the style that would later develop in music videos, with electrifying editing rhythms and an underlying soundtrack of sonically aggressive rock music. If “[physicalizing] speed” was the principal goal, this exhilarating exercise is a testament to a job well done.

In the passages between these sensorial vehicular thrills, Vanishing Point emerges as a character study – of a character who refuses to be studied. Despite Kowalski’s reticence to speak and the overall narrative minimalism, the film continually discloses brief glimpses of exposition through elliptical editing, interrupting the flow of action to chronicle his life’s story. Throughout these fragments, the viewer sees the defining moments of Kowalski’s life: a near-fatal crash during a stock car race, his intervention as a cop during the sexual assault of a young woman by a fellow officer, and the death of his lover in a surfing accident. Later, the cops will discover Kowalski’s war history, adding another traumatic experience onto his growing record. With a life immersed in tragedy, Kowalski takes shape as a man more at home weaving through the verdant green trees and dusty desert landscapes of western America than continuing onward in traditional society. Though the film will pivot to a more literal death drive as its speedy journey progresses, Vanishing Point’s signature images of this outsider indulge in stunning natural scenery, prioritizing extreme long shots of Kowalski’s Challenger as a dot on the horizon, a blip on the expansive landscape around him.

In a rite of passage for every future cult classic, initial reviews in the mainstream press were far from kind. The New York Times’ Roger Greenspun derisively framed it as a film that asks the question, “why not make a dumb movie that is nothing but an automobile chase?” Yet half a century later, Vanishing Point remains a cultural touchstone – and an object of great interest to film directors and historians. Recently, Robert M. Rubin published Vanishing Point Forever (FilmDesk Books, 2024), a mammoth, 500-page volume that assembles production documents, marketing materials, and essays from critics such as J. Hoberman, all serving as proof of the idiosyncratic film’s enduring popularity.

The legacy of Vanishing Point extends to a widely discussed association with the work of Quentin Tarantino, who references the film in his 2007 exploitation homage Death Proof. As Tarantino’s quintessentially loquacious characters chat at a Tennessee diner, New Zealand daredevil and stuntwoman Zoe (Zoe Bell) professes her desire to drive a 1970 white Dodge Challenger, with her friend instantly exclaiming “Kowalski!” in return. When another character expresses their unfamiliarity with Vanishing Point, Zoe responds incredulously: “It’s just one of the best American movies ever made!” If it’s not one of the best American movies ever made, it certainly is one of the most American, channeling the spirit of the era and the sublime pleasure of its scenery to craft a portrait of the last American hero, “that last beautiful free soul on the planet.”

Cinematalk Podcast: VANISHING POINT With Robert M. Rubin

On a new episode of the official UW Cinematheque podcast, Director of Programming Jim Healy talks with Robert M. Rubin, author of Vanishing Point Forever, a gorgeous new volume from Film Desk Books. Rubin discusses the enduring legacy of Vanishing Point (1971), director Richard Sarafian’s existential car chase classic. Rubin also talks about the essential contributions of author Guillermo Cabrera Infante, who was credited with Vanishing Point’s screenplay using the pseudonym Guillermo Cain, and the star qualities of the Dodge Challenger R/T! Vanishing Point screens for free in a new 4K DCP on Friday, July 12 and copies of Vanishing Point Forever will be available for sale before and after the screening!

New Cinematalk Episode!

On an all-new episode of our Cinematalk podcast, Cinematheque programmers Jim Healy & Ben Reiser discuss the free screenings on offer during June and July!

THE SMALL BACK ROOM: Life During Wartime

The following notes on The Small Back Room were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A newly restored 4K DCP of The Small Back Room will screen on Friday, July 5, 7 p.m., in the Cinematheque's regular venue 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is Free.

By Josh Martin

In the London war offices depicted in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Small Black Room (1949), an assortment of background signs provide a grim insistence on nightly wartime rules: “Don’t forget the blackout!” Set in 1943 at the height of the Second World War, the anxious, gloomy atmosphere engendered by the mandated preventative blackout enhances the viewer’s experience of this cinematic nocturne. As the preeminent mid-century British filmmakers, Powell and Pressburger (known collectively as The Archers) are still best known today for their elaborate use of Technicolor. Whether in service of the lavish, fantastical ballet of The Red Shoes (1948), the feverish desires of Black Narcissus (1947), or even the floral gardens of A Matter of Life and Death (1944), the legacy of the Archers is inseparable from their probing of cinematic color’s emotional and affective possibilities. However, the Archers were no strangers to the affordances of black-and-white, demonstrated by collaborations such as I Know Where I’m Going (1945) and The Small Back Room, a film that draws on moody shadows and expressionistic style to craft a tale of British despondence, resilience, and redemption.

Based on a 1943 novel by Nigel Balchin, Powell and Pressburger’s film introduces viewers to a cramped, chaotic space in the London offices of the British army, where a compendium of misfit scientists experiment with the latest in weapons technology to serve in the fight against the Germans. Operating like a disorganized, miniature Los Alamos, the “back room boys” attempt to marry their knowledge of statistics with the “feel” of weaponry as experienced by the everyday soldiers. Sammy Rice (played by David Farrar, a favorite of the Archers) is a specialist in munitions and bombs working out of this back room, but he is struggling with a disability: the loss of his foot in action. Left in endless, excruciating pain, Sammy alternates between popping pills and failing to stay away from any whiskey he can get his hands on, doing whatever it takes to mitigate the misery of his prosthetic foot. Despite the support of his love interest, war office assistant Susan (Kathleen Byron, another member of the Archers’ stock company), Sammy spends most of his time stuck in a cycle of discontent and snarky self-loathing, cynically lamenting his lot. However, Sammy finds a chance at a purpose when approached by Captain Dick Stuart (Michael Gough), who informs him of the existence of a dangerous new German bomb that the military has thus far struggled to successfully disable.

The Small Back Room arrived at a transition point in the career of the Archers. As described by Powell in his autobiography, A Life in Movies, a rift had formed between the filmmakers and J. Arthur Rank. The superproducer, who shepherded many of the Archers’ most notable triumphs of the 1940s, was profoundly unhappy with the prospects of The Red Shoes. As the Archers grew more frustrated with Rank and his lack of confidence, the independent filmmakers were also being wooed by Alexander Korda, the head of British Lion Productions. Powell approached Korda with the idea of adapting The Small Back Room, which, from his vantage point, “had a great suspense sequence” at its climax and an “ideal” role for Black Narcissus star Farrar. Korda, unfamiliar with the book, agreed to buy the rights if Powell and Pressburger were interested in adapting it for the screen. Rank ultimately decided, along with his associate John Davis, to dump The Red Shoes into theaters with little fanfare and no premiere. This decision sparked, in Powell’s words, the conclusion of “one of the greatest partnerships in the history of British films.” The Archers agreed to a five picture deal with Korda, the first of which would be The Small Back Room.

Powell and Pressburger were familiar with dramatizing British perspectives on World War II. The catastrophic conflict – and the decades leading up to it, as presented in 1943’s epic The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – had been a central subject for the directors throughout the 1940s. Far from a retread, The Small Back Room offers a distinct approach that expands on the Archers’ previous explorations of World War II-era Britain, placing an emphasis on the London home front – on the bureaucratic politics and behind-the-scenes machinations that shaped the war effort. This national portrait works in careful conjunction with the film’s more penetrating character study of Sammy Rice, whose endurance and recovery from his shattering, alcoholic despair mirrors Britain’s own comeback and ultimate victory in the war.

Though triumph is on the horizon by the film’s end, our subject matter is stark – and starkly reflected by the non-naturalistic shadows and sinister ambience of the film’s black-and-white world. Powell admitted to incorporating his love of the great German expressionist films into The Small Back Room, and we see the fruits of this influence in the surfeit of canted angles, in the cavernous, twisted spaces inside the war office – all united by the low visibility and limited illumination provided by cinematographer Chris Challis’ black-and-white compositions. Most prominently, such influence is visible in the noteworthy sequence criticized upon release by Britain’s Monthly Film Bulletin as a “lapse… into surrealistic camerawork.” One must forgive the Bulletin for its own “lapse” of judgment, as the scene in question is one of the most astonishing in the Archers’ filmography.

Resembling the Salvador Dalí-designed interlude in Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) or, perhaps more aptly, the drunken dreams of grandeur by Emil Jannings’ lowly porter in F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924), Powell and Pressburger present an assortment of nightmarish sounds and images that represent the inner turmoil of Sammy, now at his lowest point in the film. As a clock ticks loudly in the soundscape, the camera lingers on Sammy’s gaze, fixated on a whiskey bottle. The clock grows louder, with the film alternating between images of the clock’s inner workings and striking close-ups of a pained look on Sammy’s face. Eventually, the scene itself morphs into an abstract and distorted space, inundating Sammy and the spectator with strange visual reminders of his addictions, failings, and overwhelming fears. The whiskey bottle grows larger, the alarm clock becomes louder, and our tortured protagonist finds himself one step closer to his breaking point.

This commitment to formal innovation is evident throughout The Small Back Room, from the exchange of intimate close-ups on Farrar and Byron’s expressive faces to the meticulous tension of the climactic bomb disposal, a quiet exercise in stillness and unease. Down on his luck and in dire pain, facing a high likelihood of death, Sammy still approaches the bomb hoping for some insight that could help beat the Germans. “Are you sure you can manage?” the captain asks. With a typically British stiff upper lip, Sammy can only chuckle and smile, responding: “Suppose I’ll have to.” In a resurgent moment for the Archers in contemporary film culture, highlighted by the North American tour of the British Film Institute’s “Cinema Unbound” retrospective and the forthcoming release of the Martin Scorsese-produced Powell/Pressburger documentary Made in England, The Small Back Room is a prime candidate for rediscovery and further appreciation. Among their many canonized classics, the film remains a key chapter in their oeuvre, a visually accomplished character study that doubles as an essential work of postwar British self-mythologizing.

The Clockwork Precision of SPEED, 30 Years Later

The following notes on Speed were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A 35mm print of Speed from the Wisconsin Center for Film & Theater Research will be screened on Wednesday, July 3, at 7 p.m., in our series tribute to the late David Bordwell. Admission is free

By Josh Martin

“Speed (1994) exemplifies the fairly well-crafted action picture. You can say it has three acts (bomb on elevator/on bus/on subway train), or Thompson’s four parts (with a midpoint stakes raiser, the death of an innocent bus passenger, proving that the bomber is willing to kill everyone). The running motifs do causal work. The bomber is watching a televised football game featuring the Arizona Wildcats, and in phone conversation with Jack, the cop on the lethal bus, he refers to Annie, the woman driving, as a ‘wildcat.’ Only later will Jack realize that the bomber can see Annie’s Arizona sweater, so there must be a video camera aboard. The ‘pop quiz’ line answered by Jack’s flippant ‘Shoot the hostage’ at the film’s start recurs at the end, but now Annie is the hostage, and Jack cannot follow his own maxim. Both motifs tie into a broader arc of Jack’s character. At the beginning he’s valiant but impetuous, and his mentor, Harry, warns him that he’s going to have to learn to think if he’s to survive. The bomber mocks Jack for the same reason: ‘Do not attempt to grow a brain.’ But when Jack concludes that the bomber is monitoring the bus, he devises a way to send looped video footage to the bomber while the passengers escape. At the Climax, Jack can use his recklessness strategically: with the subway train hurtling out of control, he realizes that he must accelerate. In the course of his adventure, Jack’s boldness gets tempered by wiliness and prudence. This is not a moral education worthy of Henry James, but it’s enough to bind the suspense and stunts into a reasonably well-contoured whole” (David Bordwell).

Bordwell’s analysis of Jan de Bont’s action classic Speed (1994) emerges in the context of a broader look at modern action cinema in his 2006 book, The Way Hollywood Tells It. Rejecting a cynical reading of action films in which “spectacle overrides narrative,” Bordwell instead sketches a vision of the genre contingent on “all the standard equipment of goals, conflicts, foreshadowing, restricted omniscience, motifs, rising action, and closure.” “Far from being a noisy free-for-all,” Bordwell writes, “the industry’s ideal action movie is as formally strict as a minuet.” De Bont’s film thus serves as an exemplar of how such “equipment” works in the modern action genre, producing a form that blends extravagant thrills with key narrational work.

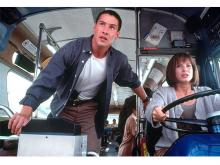

What strikes the viewer about Speed, both from Bordwell’s assessment and one’s own engagement with the picture, is its impressive economy in fulfilling these classical norms. Here we have a film that rarely slows down, instead providing character depth and narrative information through action, often by employing clear and cogent cinematic grammar. The rather simple scenario is nonetheless handled with skill, intricacy, and precision, operating in tandem with a rapid pace and sense of energetic urgency. The film follows Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves, in prime form), a hotshot LAPD bomb squad member who recently succeeded in thwarting an elevator bombing by an aggrieved terrorist (an amped-up Dennis Hopper). As an act of revenge, Hopper’s bomber rigs a Santa Monica city bus to explode if his monetary demands are not met. If the bus accelerates over 50 miles per hour, the bomb will be activated. If the bus subsequently slows below this 50 mph threshold, it will explode. If the LAPD tries to remove the passengers from the bus, it will explode. These are the conditions in which Jack must save the lives of the ordinary Angelenos who happen to board this doomed vehicle.

One of Speed’s many strengths is its casual evocation of the day-to-day lives of the bus riders, succinctly crafting dynamic characters who exemplify the diversity of the city in microcosm. The nervous Helen (Beth Grant), who will later panic in the face of this dangerous endeavor, mentions that she started riding the bus due to stress: “I just couldn’t handle the freeways anymore. I got so tense.” Self-proclaimed “yokel” Stephens (Alan Ruck) is the quintessential LA tourist, confused by the airport and the city’s insufficient networks of transportation. Annie, played by Sandra Bullock in her breakout role, receives an especially snappy characterization. Aside from some small essential details – her revoked license, and her attendance at the University of Arizona – the film is ultimately uninterested in an elaborate backstory that would bog down the pace. The viewer meets her in a moment of high stress: chasing down the city bus, coffee in one hand, cigarette in the other. From the smirking reaction of bus driver Sam (Hawthorne James), this is part of Annie’s everyday routine – it’s just another day on the LA bus lines.

Of course, such expertly staged metropolitan mundanity only carries any weight in contrast to the intensity of Speed, a picture that deliberately heightens its pace – and its performances – to match the playfully choreographed chaos. Dennis Hopper, eight years after David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), brings a similar villainous ferocity to his role as the bomber, whose boisterous bellowing and unpredictable fury provide a sublime foil to the stoic Jack Traven. Reeves, ice cold off his widely criticized performance in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1993), is a natural fit as the sharp, cool-as-a-cucumber Traven, further honing the action star persona he began crafting as early as Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break (1991). Paired with the nascent everywoman charisma of Bullock, our three leads make for a formidable trio, helping to smoothly execute the narrative norms and beats that Bordwell emphasizes.

Far from just a showcase for its stars’ well-honed personalities, Speed is also one of the definitive Los Angeles movies, a city symphony that presents obstacles and details only possible in the smog-covered city of Angels. “LA is one large place,” Stephens quips at one point, and the film eagerly makes use of this sprawling landscape. Los Angeles is built upon a complex network of freeways, a web that enables high-speed pursuits and the omnipresent threat of stultifying traffic jams. De Bont, who served as the cinematographer for fellow LA actioner Die Hard (1988) before making his directorial debut here, uses the idiosyncrasies of the city to the fullest, exploiting the narrative challenges presented by construction hazards, the inescapable visibility of hovering local news cameras, and the threat of ravenous reporters. By the time Jack and Annie send a subway car crashing onto Hollywood Boulevard, landing in front of delighted tourists at the Chinese Theatre, the film’s portrait of everyday LA slyly gives way to an ending only possible in the movies. Hooray for Hollywood, indeed.

In a decade that produced a surplus of high-octane action filmmaking – from the continued reign of Die Hard’s John McTiernan to the emergence of Michael Bay’s signature mayhem – Speed remains a high point of the era. In the introduction to The Way Hollywood Tells It, Bordwell offers a defense of his study of classical norms, conventions, and “ordinary” films, writing that the interrogation of these norms allows us to “better appreciate skill, daring, and emotional power on those rare occasions when we meet them.” On its thirtieth anniversary, de Bont’s picture remains one such occasion: a beacon of classical Hollywood craftsmanship and its enduring ability to thrill the spectator.

DAYS OF HEAVEN: Magic Hour (and a Half)

The following notes on Days of Heaven were written by Will Quade, PhD Candidate in the department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A new 4K DCP of Days of Heaven screens on Friday, May 3, at the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue. Admission is Free!

By Will Quade

French composer Camille Saint-Saëns’ spine-tingling classical piece “Aquarium” hovers like a ghost over the drama within Terrence Malick’s revered second feature Days of Heaven. The music is first placed over the film’s opening credits, where documentary photographs of people working, living, and playing in the 1910s dissolve into each other before Malick ends on one final image: a lone preteen girl, Linda (Linda Manz) – huddled over, knees scrunched to her chest – staring right at the viewer. It is this girl, and Manz’s remarkably vivid voiceover, who will anchor us throughout the film’s dreamy narrative.

The mix of overpowering music, small human drama, and rigorous historical grounding that made Days of Heaven an instantly formidable American film are, by now, part and parcel of what we know as the overall Malick style. While his first film, Badlands (1973), still utilized the trademark pastoral photography he would only become more renowned for, that movie’s conventional lovers-on-the-run premise seems shockingly clear in comparison to Days of Heaven’s almost anti-narrative ethos. Even during the film’s opening few minutes, one can’t help but ask themselves certain questions: where did this strange style come from? Who is responsible for this non-stop barrage of jaw-dropping images? What drove this filmmaker to tell this story this way?

Often discussed in almost cryptid-like terms, the notoriously private Malick was not originally a filmmaker. Graduating summa cum laude at Harvard in 1965, he became a Rhodes scholar in philosophy with a specialization in the works of Martin Heidegger. While never finishing his degree, his translation of Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons was published by Northwestern University Press in 1969. A philosopher by trade, Malick’s attention was drawn to cinema. After receiving an MFA from the brand-new AFI Conservatory, he found steady work in the industry as a writer and the success of Badlands made Paramount anxious to work with him on a bigger project. What followed was the script for Days of Heaven. But what was originally a smaller, more manageable film about an impoverished con-artist couple trying to marry into the enormous wealth of a dying farmer soon snowballed into a tumultuous production process that rivaled other New Hollywood classics like Sorcerer, Apocalypse Now, and Heaven’s Gate.

Taking place in the Texas Panhandle but shot primarily in Canada, one of Days of Heaven’s most striking aspects is its use of “magic hour” photography to capture footage of the 15-20 mins of golden daylight remaining just before dawn or right after dusk. While this footage is clearly integral to the film’s dazzling imagery, the pain-staking process of shooting this resulted in a near-mutiny from the crew on set. As production languished, cinematographer Nestor Almendros was slowly becoming blind and eventually had to leave the project to lens another one, resulting in director of photography Haskell Wexler finishing what he started. The script was tossed mid-shoot to allow for maximum improvisation. This meant daily call sheets and shooting schedules were constantly changing, angering the crew further. The film ended up taking two full years to edit as Malick switched creative directions and enlisted Manz to provide a backbone of voiceover narration, effectively making her the central protagonist.

All the tumult in the years-long journey of making Days of Heaven still managed to yield instant accolades. Malick won the Best Director award at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival and from the National Society of Film Critics, and Ennio Morricone was nominated for an Academy Award and won a BAFTA Award for his score. Almendros won an Oscar for his cinematography but—true to the film’s acrimonious production—Wexler crusaded for a co-credit (and Oscar statuette) for his work after replacing him. The entire ordeal exhausted Malick. He retreated from Hollywood, dropped out of all public life, and moved to France. The mystique around Malick himself continued to grow in his absence, seemingly encouraged by Days of Heaven’s hazy and tender tone. The sensitivity of the film’s approach and its towering photography turned the director into a somewhat-deified “missing poet” of American cinema. While Malick did appear 20 years later in 1998 with his World War II epic The Thin Red Line and has continued to make films into his eighties, the elements that make him the director he is today are all present in the conception, production, and reception of Days of Heaven.

Malick has continued to craft productions that remain vague, discombobulate crews, disappoint actors, and make little money. The reception of his films from critics has only become more divided as his works have drifted closer to legitimately experimental film in his late career. But Days of Heaven remains his unimpeachable early career achievement if for no other reason than it serves as something of an origin story for one of the most iconic directors in the history of Hollywood cinema. However, its overall quality goes beyond just the craft and reputation of Malick himself.

Manz’s magnetic performance and perceptive voiceover showcase another dazzling light demanding the viewer’s attention along with its awe-inspiring vistas. As the character Linda matures over the course of the film, we feel Manz the actor doing the same. Her questioning, timeless descriptions reflect the philosophical interests of Malick, especially his interest in the sublime quality of nature. In the end, the young girl in the black-and-white photograph from the opening credits seems to be recounting to us her own days of heaven; not ones without hardship and strife, but still representative of a time that encompassed the most resplendent memories of her young life. The gob-smacking beauty of Linda’s story is both wondrous and terrifying, giving and damning. Watching Days of Heaven recalls critic Fernando F. Croce’s praise of Malick’s 2005 feature The New World: “It makes you view the world with virgin eyes again.”

Message from The Visitor: THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH

The following notes on The Man Who Fell to Earth were written by Max Kaplan, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A 35mm print of The Man Who Fell to Earth will be the final screening in our Cinematic Messages from Our Planet series at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, April 28 at 2 p.m. The Chazen is located at 750 University Avenue. Admission is free.

By Max Kaplan

For a man who went by many names as a musical artist, David Bowie assumed many more throughout his cinematic career. While his film credits notably spawned fantastical creations such as Jareth, The Goblin King in Labyrinth (1986) and the vampire cellist John Blaylock in The Hunger (1983), Bowie also stepped into other uniforms (and dimensions) as Major Jack Celliers in Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (1983) and the enigmatic Agent Phillip Jeffries in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992). Meanwhile, Hollywood’s fascination with Bowie’s star power led to him being cast in larger-than-life historical roles, such as Pontius Pilate in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Andy Warhol in Basquiat (1996), and Nikola Tesla in The Prestige (2006). Yet much of Bowie’s brilliance could be attributed to his capacity to juggle such eclectic roles alongside his already highly conceptual persona as a pop auteur. As Katherine Reed notes, “For many entertainers, such malleability of not only character but self would be seen as a liability. Bowie sought to capitalize upon it.” The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) marked Bowie’s foray into feature film stardom. Even more so than his filmic roles of the 80s and beyond, his appearance in Nicolas Roeg’s arthouse sci-fi classic felt strategically aligned with the otherworldly persona he’d spent the better half of a decade cultivating. Depending on how one looks at it, The Man Who Fell to Earth could even be regarded as the one true “David Bowie film.”

In 1976—and in typically cryptic Bowie fashion—Bowie proclaimed that he had “been making films on records for years now.” Before ‘high concept’ became a Hollywood buzzword, David Bowie was churning out conceptual, cinematic rock albums like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), Aladdin Sane (1973), and Diamond Dogs (1974). With 1975’s Young Americans, Bowie ditched his British glam rock roots for the American soul idiom, trading the sci-fi gimmick for cocaine-fueled American hedonism—foretelling a critical dichotomy at play throughout The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie, in fact, began work on a soundtrack for the film, originally intended as his follow-up to Young Americans, but the album fell through due to reports of drug-induced fatigue and contractual disputes. What remained from the aborted sessions were several breakthroughs that would inflect Bowie’s later sonic endeavors: namely, an interest in creating atmospheric “mood music” as well as a first inkling of collaborating with the wizard of atmospherics himself, Brian Eno. But these artistic breakthroughs would not find full bloom until Bowie’s legendarily drugged-out recording sessions in Berlin.

Like Bowie, director Nicolas Roeg was an Englishman with a cosmopolitan impulse. Roeg began his career as a cinematographer, working second unit on films like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) before graduating to director of photography for Roger Corman’s Masque of the Red Death (1964). Following his leap to directing with the East London crime drama Performance (1970)—which starred Mick Jagger—Roeg traveled to Australia and Venice, respectively, to shoot Walkabout (1971) and Don’t Look Now (1973). With his first filmed-in-America production, Roeg was seduced by the vastness of the western landscape that many New Hollywood auteurs (Malick, Altman, Bogdanovich, and others) had mined for cinematic gold. Yet for as many hallmarks of the New Hollywood style that Roeg conjures, The Man Who Fell to Earth feels more in tune with the alien perspective of an international production, feasting on the absurdity of American society from a position of other-worldly alterity.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is science fiction in name and scope, but in both sound and vision, it bears the idiosyncratic artistic trademarks of its times. Doing double duty on the soundtrack is John Phillips, of The Mamas & the Papas fame, and Stomu Yamashta, the Japanese experimental percussionist who previously created the eerie, pastoral soundscapes for Robert Altman’s Images (1972). In relieving soundtrack duty from Bowie himself, Phillips’ tunes run across the board, from the Bonnie & Clyde-esque “Bluegrass Breakdown” to the loungey jazz of “Alberto” to the space funk of “Windows.” Yamashta’s contributions inhabit the more abstract spaces of the film’s soundscape from the Western shrubland all the way to the barren terrain of Thomas Jerome Newton’s home planet, adding surreal textures to the protagonist’s disorientation. Visually, Tony Richmond’s cinematography captures the glimmering palette of boundless wealth, amusement, and alienation that subsume Newton entirely, making The Man Who Fell to Earth a film so thoroughly packed with iconic audiovisual moments. For a film that is often associated with its leading man, The Man Who Fell to Earth is an all-hands-on-deck offering of 70s auteur cinema in all its indulgent, off-kilter creativity.

Returning to Bowie, near the film’s end, we catch a brief glimpse of Bryce passing by Bowie’s Young Americans on display at a record store. However, as we soon learn, the album that attracts Bryce’s attention turns out to be a mysterious record called The Visitor, which appears to have been recorded by Newton himself. While Bowie’s music is conspicuously absent from the soundtrack, it has since become clear that the film bore a significant impact on Bowie’s musical trajectory. Fans will notice that his next two albums—Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977)—use stills from the film on their covers. Both albums now stand among Bowie’s most critically acclaimed and beloved by fans. Beyond that, Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy, beginning with 1977’s Low, ultimately allowed Bowie to not only work with Eno, but also to produce the atmospheric mood music that he had conceptualized during the production of The Man Who Fell to Earth. But what really makes the film the ‘most Bowie’ in terms of his film roles lies in the character of Thomas Newton, who subsequently became subsumed in what Lisa Perrott calls the ‘loose continuity’ of Bowie’s iconography. Joining the ranks of Major Tom, Ziggy Stardust, Halloween Jack, The Thin White Duke, Pierrot and other Bowie characters that recur throughout his transmedial oeuvre, the specter of Newton leaves a hauntological trace throughout Bowie’s subsequent work, notably being referenced in later music videos for “Little Wonder” and “No Plan.”

Around the film’s midway point, Newton tells a baffled Bryce that yes, in fact, “there have always been visitors.” Following Bowie’s untimely death in 2016, admirers and critics alike have sought meaning in his otherworldly artistic vision, looking to his music, painting, stage, and film careers for glimpses of the man behind the many guises. The Man Who Fell to Earth offers no clear-cut answers, but through it, we can relish a cinematic vision that solidified Bowie’s multifaceted star persona and inspired a whole generation of visitors to explore new audiovisual realms.