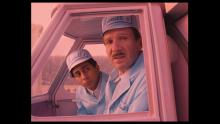

These notes on Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. The Grand Budapest Hotel will screen in the second part of our Thank You, David Bordwell series on Friday, August 30 at 7 p.m. in our regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. The screening will be followed by David Bordwell's video essay discussing Wes Anderson's visual style.

By Josh Martin

“There are still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity,” muses lobby boy-turned-reclusive hotel proprietor Zero Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham) in the final moments of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Spoken with the “imperceptible air of sadness” that the film’s novelist narrator identifies early in the picture, Zero offers one final remark: “He was one of them.” That faint glimmer in question is Monsieur Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes), the meticulously mannered, quick-witted, and often hysterically profane concierge of the film’s titular establishment. Gustave is many things – a poet, a philanderer, a precise and dutiful manager – but above all, he is a man of decency and honor. At this stage of the film, Zero’s tribute to his friend and mentor is also a lament, a mourning of the loss of a man whose principles and dignity, much like the “enchanted old ruin” he managed, left him at odds with an increasingly violent and desolate age. “His world had vanished long before he ever entered it,” Zero opines, “but he sustained the illusion with a marvelous grace.” Imbued with that indefatigable grace by Fiennes, Gustave H. is the melancholy center of gravity in Anderson’s crown jewel, a film that remains an indelible creation.

Like many of Anderson’s recent works, which experiment with storytelling structures such as the stage-play-within-a-fictional-TV-show-within-a-film of last year’s Asteroid City, or the anthology of newspaper articles recalled by their scribes in 2021’s The French Dispatch, The Grand Budapest Hotel employs a complicated narrative approach matched by its play with aspect ratios, colors, and other elements of form. The film opens with a young girl visiting a memorial site for an author (Tom Wilkinson), whom we are told is one of the literary gems of the fictional European land of Zubrowka. The girl is carrying a copy of one of the author’s best-known works: The Grand Budapest Hotel. Here, Anderson cuts to the author of the novel in question, who remembers his time in the 1960s as a young man (now played by Jude Law) at the Grand Budapest. It was during this stay that he learned the tale of Mr. Moustafa, who regaled him with the loopy account of how he acquired this property in the 1930s – the story that eventually became the author’s novel. Anderson presents these layers of storytelling and artifice with an impressive clarity throughout, with the metafictional structure unfolding smoothly for the viewer.

The plot of The Grand Budapest Hotel itself is zippy, matched by the rhythmic, playful tempo of Alexandre Desplat’s Oscar-winning score. Anderson revels in his tale’s twists and extreme convolutions – knotty phrases such as “the second copy of the second will” come to make perfect sense in a world divorced from any kind of realism. This sense of play extends to the film’s engagement with various genres, defying a simple classification in favor of a knowing smorgasbord of popular forms. The bildungsroman, the murder mystery, the war film, prison break pictures, even a set piece that echoes slasher movies – all are present in Anderson’s metamorphic work. Yet even as it evolves and shifts beneath the viewer’s feet, the film orbits around Fiennes, whose first collaboration with Anderson (he would later reteam to play a panoply of roles in the director’s 2023 Roald Dahl shorts) brings the scrupulous clerk to life with specificity and vividness. The British thespian demonstrates an instinctual feel for the director’s rat-a-tat dialogue, exemplifying Gustave’s prim-and-proper formality and his deliciously combative sense of superiority (“You wouldn’t know chiaroscuro from chicken giblets”).

Yet in an interview with The Daily Beast, Fiennes describes Gustave as “quite alone,” with his cheeky performance of dutiful service acting as a “persona” to veil his more turbulent emotions. More than just a superlative comic turn, Fiennes imbues in Gustave a tenuous balance between the humorous and the melancholic – a balance that is essential to an understanding of the film’s broader milieu. Despite its tinkering with genre and heightened environments, The Grand Budapest Hotel is a film principally concerned with the looming clouds of war – with the violence and prejudice that emerged at the twilight of one age and the dawn of another, pointedly addressing Zero’s status as an immigrant and the xenophobic sentiments that arose around this fictionalized portrait of World War II.

Such tonal clashes and thematic concerns can be traced back to the source material. In the closing credits, Anderson acknowledges the inspiration of Stefan Zweig, the Austrian author of novels such as Letter from an Unknown Woman who left Europe in the 1930s amid rising antisemitism and fascism. During an interview with Anderson, Zweig biographer George Prochnik describes the film’s “fairy tale dimension” signified by the blend of a “confectionary” style and “black” humor as matching the tenor of Zweig’s own writings. Indeed, The Grand Budapest Hotel is such a feast of candy-colored pastel palettes that one is almost startled by the slow incursion of depravity into its narrative. Hints of unexpected discordance are visible early – Anderson loves sudden non sequiturs and digressions – but as the film progresses, the onslaught of decapitations, dead cats, and severed fingers further disturb the frothy mood.

Anderson is a filmmaker often reduced to a set of recognizable aesthetic idiosyncrasies: symmetrical frames employing what David Bordwell describes as “planimetric style,” visual incongruity, mannered dialogue. As such, the director is often accused of being emotionally distant and socio-politically opaque, a formalist hamstrung by that dastardly label of “style over substance.” Though this contention deserves further scrutiny, The Grand Budapest Hotel is a particularly strong refutation, with Anderson’s style and his themes operating harmoniously in tandem. The affectations and lovingly controlled frames – arranged with as much rigor and purpose as Monsieur Gustave’s hotel – serve as counterpoints to Grand Budapest’s more morose sensibilities, with characters whose stylized mannerisms fail to fully obscure lives marred by tragedy.

An emphasis on Grand Budapest’s solemnity and sociopolitical reflections could, perhaps, dampen an audience’s interest, lest they be subjected to a moody and downbeat experience. However, the pleasures of the film’s form and narrative are so immediate and immense – so evidently delectable for the spectator – that those depths of theme and feeling slowly creep up as the film continues, growing in profundity and capaciousness with each return to Anderson’s world. A decade after its initial critical and financial success, The Grand Budapest Hotel remains beloved in part because it is something of a magic trick, fusing its competing tones, genres, and emotional registers with, to return to Zero’s words, the kind of “marvelous grace” that even Monsieur Gustave would envy.