LA PETITE LISE and DAÏNAH LA MÉTISSE: Experiments at the Dawn of Sound

This essay on Jean Grémillon's La petite Lise (1930) and Daïnah la métisse (1932) was written by Jonah Horwitz, Ph.D candidate in UW Madison's Department of Communication Arts. Both films will screen in 35mm on Saturday, September 19, at 7 p.m. in 4070 Vilas Hall.

By Jonah Horwitz

The two films in Saturday's double feature reveal their director, Jean Grémillon, at his most daring and experimental. It will probably not surprise students of film history, then, that both La petite Lise (1930) and Daïnah la métisse (1932) were miserable commercial failures in their day.

La petite Lise, Grémillon's first sound film, was made after two remarkable silent features, Maldone and Gardiens de phare. Their success led the producer Bernard Natan, who had recently acquired the powerful Pathé studio (renaming it Pathé-Natan), to hire Grémillon. Grémillon collaborated with screenwriter Charles Spaak on two screenplays that the commercially-minded Natan rejected as too experimental. Their third script, La petite Lise ("Little Lisa"), was thus deliberately written as a sordid melodrama to appease Natan. The story could not be simpler: Berthier (Pierre Alcover), a convict in a colonial prison, awaits his release and a reunion with his beloved daughter Lise (Nadia Sibirskaïa, born Germaine Lebas in Brittany). On his return to Paris, he discovers that Lise is living in sin and squalor with a down-and-out musician, André (Julien Bertheau). Lise and André eventually commit a gruesome crime, and Berthier—well, you get the idea.

If La Petite Lise's plot is deliberately elemental, its style is anything but. The film was made in 1930, the first full year of the sound film in France. When historians write of this period of French cinema, they often refer to competing theories or approaches to the newly audio-visual medium. One approach, the film parlant ("talking film"), tended toward adaptations of plays, with a heavy reliance on dialogue directly recorded on set. The alternative approach, the film sonore ("sound film"), utilized post-synchronized sound in order to achieve a more playful, non-naturalistic mix of music, effects, and dialogue. Grémillon was likely more sympathetic to the latter approach. Synchronized dialogue is just one—and far from the most common—sonic element in La petite Lise. More often, we see one thing and hear another—or see something long after we hear it. Sometimes, Grémillon will let the sound from one space play "over" images of another space altogether, leaving the audience to contemplate the meaning of the disjuncture. Grémillon also experiments with the quality of sound—for instance, giving unusual expressive weight to the sound of a door slamming or nearly pulverizing the audience with blasts of industrial noise. Much like Fritz Lang's contemporaneous M, La petite Lise explores the many ways that sound and image might join, part ways, complement, and contrast. That said, Grémillon goes against the grain of the film sonore. While René Clair's effervescent musicals, such as Under the Roofs of Paris and Le Million, delight in their artificiality, Grémillon's outré technique establishes and intensifies an atmosphere of danger, oppression, and entrapment. In contrast to the fleetness of Clair's films—and like many of the films parlants—La petite Lise consists of a few protracted scenes where the weight of every movement, gesture, and spoken line is deeply felt.

This particular mix repelled Bernard Natan. After viewing a cut of Le petite Lise, he is said to have cut off communication with Grémillon and forbade his employees from speaking or working with the director. (In fairness, I should note that many nasty stories circulated about Natan, only some which are likely to be true. For more on this, see David Cairns's 2013 documentary Natan.) The film was dumped into several smaller Paris theaters without the benefit of publicity and sank with little trace. Nevertheless, a few people were paying attention. Henri Langlois, who was to become one of the most influential figures in French film culture, recalled that La petite Lise was the first film to prove to him the artistic potential of the sound film. Langlois programmed the film several times at the Cinémathèque Française, where it was seen by, among others, the future director Léos Carax. Carax includes an excerpt of La petite Lise in Mauvais sang (1986), and the shocking, documentary-style opening of his Lovers on the Bridge (1991) borrows heavily from the no-less-startling first scene of Grémillon's film, made precisely 60 years prior.

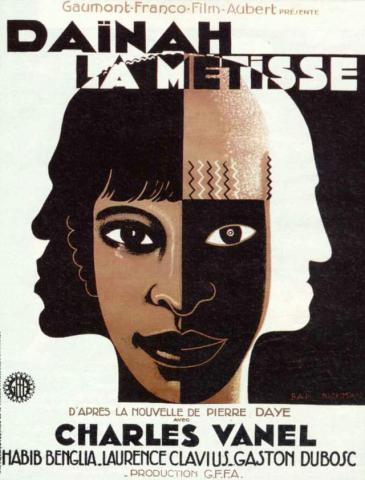

If La Petite Lise took decades to be appreciated, Grémillon's next film, Daïnah la métisse, has been even less fortunate. It deserves the designation film maudit ("cursed film"). Made as a 90-minute feature for the Gaumont studio, it was cut in half by the producers and subsequently disowned by Grémillon. It was almost entirely forgotten until a mid-1980s television screening. (It scarcely rates a mention in a 1984 monograph on Grémillon.) The full version has never been recovered. Film historian Geneviève Sellier calls it a "mutilated masterpiece."

Daïnah continues, to some extent, Lise's experiments with sound, but it arguably makes its most profound impressions through some bizarre images (including a costume ball with masks reminiscent of Ensor); an abundance of associative montage; and an unusual treatment of race, class, and gender. Daïnah, the title character, is a mixed-race woman ("métisse" means "half-breed") traveling with her black husband, a magician (Habib Benglia), aboard a passenger ship. The plot concerns a kind of deadly triangle between Daïnah, her husband, and a white, nearly preverbal ship's engineer (Charles Vanel). The drama transpires among wealthy white passengers—largely grotesques who seem oblivious to the fates of the outsiders in their midst. By today's standards, the film might seem to drape Daïnah and her husband in an excess of exoticism (it's no accident that they are associated with hot American jazz and the occult). But compared to other French films of the time, the agency, nobility, and complexity granted these characters stands out as radical. Sellier reads a feminist consciousness into that complexity. She writes that Daïnah's "flirtatiousness and contradictory behavior reflects a deep malaise: that of a beautiful woman who wishes to live freely, but whom social convention imprisons in the persona of an insufferable, 'loose' woman."

Much of Daïnah la métisse's weirdness is likely attributable to Gaumont's cuts (certainly, the narration is a bit too elliptical for comfort). The rest is no doubt due to Grémillon's audacity. That he should make a film that flaunted both stylistic and ideological convention so soon after the failure of La petite Lise nearly guaranteed that he would have trouble finding work. He spent the next few years in the proverbial wilderness, making a feature in Spain (unreleased in France), a few short films, and eventually several French-language features for the German company UFA. It wasn't until the 1939–41 production of Remorques that he would make another feature for a French company. In fact, Grémillon never found a secure footing in the French film industry. But he left behind some of the most ravishingly strange films made in that country.

A chance for Madison audiences to discover La petite Lise and Daïnah la métisse isn't likely to come around again.

Note: Much of the information included in these notes is taken from Geneviève Sellier's invaluable monograph, Jean Grémillon: Le cinéma est à vous (Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck, 1989).