The Ziegfeld of the German Musical Comedy Stage: Erik Charell and CARAVAN

This essay about Erik Charell's Caravan was written by Cinematheque Staff Member Amanda McQueen. A 35mm print of Caravan, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, will screen in the Cinematheque's "35mm Forever!" series at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, September 20, at 2 p.m.

By Amanda McQueen

In September 1934, Fox Film Corporation placed an advertisement in Variety celebrating the "Genius" of director Erik Charell. The full-page ad praised Charell's work on the musical Caravan – scheduled for release by Fox later that month – and claimed that his "Daring Originality [and] soaring imagination are reflected in every scene." "Above All," the ad concluded, Charell's first Hollywood film was something "new and significant that will be studied in every studio . . . and welcomed by a public that has been begging for a newer, truer use of the motion picture." Despite Fox's valiant promotional efforts, however, Caravan was a critical and commercial failure, ending Charell's Hollywood career as soon as it began. Today, it is being rediscovered as a major piece of Hollywood entertainment of the 1930s.

Born Erich Karl Löwenberg, Erik Charell first came to prominence as a professional dancer in Berlin, where he was often compared to Vaslav Najinski. In the 1920s – following a stint touring Europe with his own ballet company – he and his brother took over management of Berlin's Großes Schauspielhaus, and Charell started directing musical revues and operettas. Influenced by what he'd witnessed on a trip to New York, he became interested in blending German operetta with more "exotic" elements – such as jazz and Ziegfeld-style dancing girls –and his revues became famous for pushing the limits of sex, nudity, and homoeroticism on stage. Charell then turned to modernized, jazz adaptations of classic operettas, such as The Mikado and Die lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow), before collaborating with composer Ralph Benatzky on a trilogy of original works. Im weißen Rößl (The White Horse Inn) (1930) became the most successful of these three operettas: Charell himself staged productions of it in London (1931), Paris (1932), and New York (1936); it has been adapted to film multiple times, most recently in 2013; and it continues to be revived to this day.

The popularity of Charell's operettas brought him to the attention of the German film studio Ufa, and he was hired to direct Der Kongreß tanzt (The Congress Dances) (1931), a lavish operetta with music by Werner Richard Heymann and set design by Ernst Stern, who helped define the Expressionist aesthetic. The film became an international hit. The New York Times dubbed Charell the "Ziegfeld of the German musical comedy stage" and Variety, although doubtful that the film's plot would have significant interest for American audiences, nevertheless believed that its impressive visual style would "draw more than passing attention from Hollywood." That attention came in the form of a job offer from Fox, and Charell headed to California.

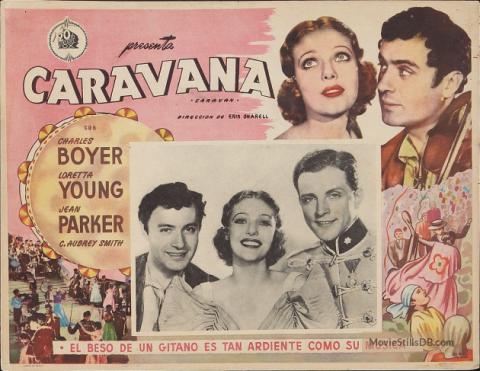

Based on an original story by Hungarian journalist Melchior Lengyel – who also wrote the stories on which Ninotchka (1939) and To Be or Not to Be (1942) were based – Caravan is similar in tone to Ernst Lubitsch's Paramount operettas starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. The plot concerns Countess Wilma (Loretta Young), who, under threat of losing her inheritance, pays the gypsy fiddler Latzi (Charles Boyer) to become her husband. However, complications arise with the romantic interferences of Lieutenant von Tokay (Phillips Holmes) and the gypsy girl Timka (Jean Parker). A French-language version, also directed by Charell, was made at the same time. Boyer, who was better known in France than America – Caravan was his first starring role in a Hollywood picture – again played Latzi, but the rest of the cast was replaced by popular European actors.

Fox saw Caravan as a follow-up to Der Kongreß tanzt, and so also brought over Heymann to write the music – in collaboration with Tin Pan Alley lyricist Gus Kahn – and Stern to handle the art design. Moreover, as part of a larger industry push to bombard the struggling film market with high-quality product, Fox planned Caravan as a "super-special," setting the budget at over $1 million, touting the film's "mass effects involving thousands of people," and promising a "Spectacle of such sheer beauty that nothing ever done on the screen can compare with it." A key part of this spectacle-centered promotion emphasized the unique contributions of Charell as director. In June 1934, for example, Fox advertised that they had secured "Europe's prize long-run producer (his hits run for years!)" and had "backed him to the limit" with all the resources the studio could supply.

But Caravan fell far short of Fox's high expectations. Reviews were almost entirely unfavorable. The New York Times found the musical "an exceptionally tedious enterprise," while Variety thought it "heavy-handed, cumbersome and overloaded with a crazy kaleidoscope of mass production." Audiences seem to have agreed, and Caravan performed poorly at the box office, with many theaters pulling the film after only a few days. The French version didn't fare much better.

In the wake of Caravan’s failure, other Hollywood producers cancelled their projects with Charell. And with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany, Ufa, too, had severed ties with the Jewish director. So Charell returned to the stage, mounting the Broadway production of The White Horse Inn (1936) to much success, and experimenting with a jazz operetta version of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Charell's Swingin' the Dream (1939) featured music by Jimmy van Heusen and Benny Goodman, choreography by Agnes DeMille, and performances by Louis Armstrong, Dorothy Dandridge, Butterfly McQueen, and Count Basie. Unfortunately, it closed after only 13 shows. After the war, Charell returned to Germany and musical theater, but his film work was limited to producing adaptations of two of his operettas: Im weißen Rößl (1952), starring Johannes Heesters, and Feuerwerk (Fireworks) (1954), starring Lilli Palmer and a young Romy Schneider.

Caravan's disappointing performance is perhaps responsible for its near-disappearance over the past 80 years. Yet the musical's recent restoration, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art's nitrate collection, seems to be bringing about a new appreciation for Charell's directorial skill. Indeed, even upon the film's initial release, reviewers admitted that Caravan possessed "photographic charm" and that "Charell is a master at camera supervision." Employing cranes, tracks, and possibly the proto-Steadicam "Velocilator," Charell makes Caravan – in the words of critic R. Emmet Sweeney – a "perpetually moving marvel, pirouetting through the gypsies like a fellow reveler." Also boasting innovative editing, a supporting cast of superb character actors, and, of course, the lovely Loretta Young and the dashing Charles Boyer, Caravan is being hailed as a major cinematic re-discovery.