By Jim Healy, Director of Programming

In a terrific interview with Vulture last month, complete flim-maker John Carpenter (whose action masterpiece, Escape from New York will have a Cinematheque/WUD Film screening next month) answers a question about the Ennio Morriconne score for his 1982 remake of The Thing. Carpenter, who typically composes the music for his films, talks about his preference for minimalist music in movies, as opposed to the "Mickey Mouse-ing" of something like Max Steiner's score for King Kong, where, as Carpenter says:

"The footsteps of King Kong are scored: bom-bom-bom. Mickey Mouse–ing is over-scoring. It's what happens today. Everything is over-scored. Minimalist music, a lot of it from my time — '60s, '70s, and '80s. Tangerine Dream did some. The Exorcist's score is another. They weren't Mickey Mouse scores. By Mickey Mouse, I don't mean dumb, or cartoonish, but everything was musically it: footsteps, everything."

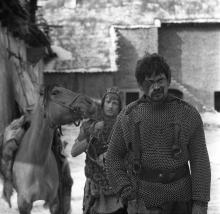

Tangerine Dream, of course, got their first offer to score a Hollywood film from director William Friedkin, who invited the German musicians to score his 1977 existentialist action movie, Sorcerer. Friedkin discovered the trio, then made up of Edgar Froese, Christopher Franke, and Peter Baumann, performing their special brand of electronic music at a concert in an abandoned chruch in Germany's Black Forest. Instead of having the band score the film after it was shot and edited, which is what usually happens, Friedkin sent Tangerine Dream the script. Friedkin had them read it and the band recorded their musical impressions which Friedkin used to establish rhythm when assembling the footage with editor Bud Smith. Despite the fact that Sorcerer was rather famously rejected by audiences and most critics when first released, the score proved highly influential and led to steady work for Tangerine Dream in movies, most notably Michael Mann's Thief, Paul Brickman's Risky Business, Kathryn Bigelow's Near Dark, and the American release version of Ridley Scott's Legend (which, in its international release version, had a very fine, if slightly MIckey Mouse-y score by Jerry Goldsmith).

You can hear Tangerine Dream's Sorcerer score for yourself this Thursday, October 9, when the UW Cinematheque and WUD Film present a new DCP restoration of Friedkin's riveting adventure. For now, here's a little musical prelude:

Friedkin has always been a director who pays close attention to sound design and music is always a big part of that design. The director brought on experimental jazz musician Don Ellis for The French Connection and, in the 80s, hired pop rockers Wang Chung to write songs and a score for To Live and Die in L.A. (Ben Reiser reflects on that movie music here). Before his biggest box-office hit, 1973's The Exorcist wound up with the eclectic, minimalist score mentioned above by John Carpenter, Friedkin commissioned a score from then in-vogue composer Lalo Schifrin, whose body of work then included the theme for Mission: Impossible and the scores for Bullitt, Dirty Harry and another colossol 1973 hit, Enter the Dragon. While Friedkin found Schifrin's music abstract enough when he first heard it played back on piano, the director was not pleased when the score was recorded by a 70-piece orchestra (at the same Warner Bros. facility where Max Steiner recorded his scores in the 30s, 40s and 50s). According to Friedkin, "[The score] was wall-to-wall noise, using every component of this big band, including electric brass...I was in shock. It's not that the music was badly written or played; but it was the opposite of what I wanted."

Friedkin rather notoriously discarded Schifrin's work, effectively destroying their friendship, and replaced the score with pre-existing cues by Anton Webern, Krzysztof Penderecki, and, of course, Mike Oldfield, whose "Tubular Bells" helped launch Richard Branson's Virgin Records because of its inclusion in The Exorcist. Friedkin's move was not unprecedented in Hollywood history: Stanley Kubrick rejected a score by Alex North for 2001: A Space Odyssey in favor of the now famous pre-existing cues by Johann Strauss and Richard Strauss.

While "Mickey Mouse" scoring continues its dominance (consider Hans Zimmer's overdone music for Disney's production of The Lone Ranger as one example), the kind of minimalist scoring preferred by Carpenter and Friedkin in Sorcerer and The Exorcist has its contemporary descendants, like the music Johnny Greenwood has written for Paul Thomas Anderson's most recent films and the Carpenter-esque scores by Kurt Stenzel for Jodorowsky's Dune and Steve Moore for The Guest.

The Exorcist screens tonight, October 8, at 7 p.m. in the Marquee Theater at Union South. The 2000 re-release version, featuring added footage not seen in the original 1973 release, will be shown. A newly restored DCP of Sorcerer screens Thursday, October 9 at 7 p.m. at the Marquee Theater at Union South. Both screenings are co-presented by Cinematheque and WUD Film and both are free and open to the public.