The Clockwork Precision of SPEED, 30 Years Later

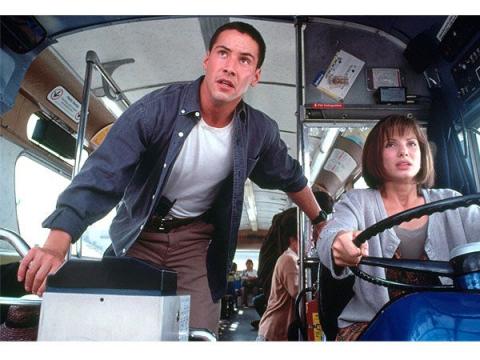

Keanu Reeves & Sandra Bullock in SPEED

The following notes on Speed were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A 35mm print of Speed from the Wisconsin Center for Film & Theater Research will be screened on Wednesday, July 3, at 7 p.m., in our series tribute to the late David Bordwell. Admission is free

By Josh Martin

“Speed (1994) exemplifies the fairly well-crafted action picture. You can say it has three acts (bomb on elevator/on bus/on subway train), or Thompson’s four parts (with a midpoint stakes raiser, the death of an innocent bus passenger, proving that the bomber is willing to kill everyone). The running motifs do causal work. The bomber is watching a televised football game featuring the Arizona Wildcats, and in phone conversation with Jack, the cop on the lethal bus, he refers to Annie, the woman driving, as a ‘wildcat.’ Only later will Jack realize that the bomber can see Annie’s Arizona sweater, so there must be a video camera aboard. The ‘pop quiz’ line answered by Jack’s flippant ‘Shoot the hostage’ at the film’s start recurs at the end, but now Annie is the hostage, and Jack cannot follow his own maxim. Both motifs tie into a broader arc of Jack’s character. At the beginning he’s valiant but impetuous, and his mentor, Harry, warns him that he’s going to have to learn to think if he’s to survive. The bomber mocks Jack for the same reason: ‘Do not attempt to grow a brain.’ But when Jack concludes that the bomber is monitoring the bus, he devises a way to send looped video footage to the bomber while the passengers escape. At the Climax, Jack can use his recklessness strategically: with the subway train hurtling out of control, he realizes that he must accelerate. In the course of his adventure, Jack’s boldness gets tempered by wiliness and prudence. This is not a moral education worthy of Henry James, but it’s enough to bind the suspense and stunts into a reasonably well-contoured whole” (David Bordwell).

Bordwell’s analysis of Jan de Bont’s action classic Speed (1994) emerges in the context of a broader look at modern action cinema in his 2006 book, The Way Hollywood Tells It. Rejecting a cynical reading of action films in which “spectacle overrides narrative,” Bordwell instead sketches a vision of the genre contingent on “all the standard equipment of goals, conflicts, foreshadowing, restricted omniscience, motifs, rising action, and closure.” “Far from being a noisy free-for-all,” Bordwell writes, “the industry’s ideal action movie is as formally strict as a minuet.” De Bont’s film thus serves as an exemplar of how such “equipment” works in the modern action genre, producing a form that blends extravagant thrills with key narrational work.

What strikes the viewer about Speed, both from Bordwell’s assessment and one’s own engagement with the picture, is its impressive economy in fulfilling these classical norms. Here we have a film that rarely slows down, instead providing character depth and narrative information through action, often by employing clear and cogent cinematic grammar. The rather simple scenario is nonetheless handled with skill, intricacy, and precision, operating in tandem with a rapid pace and sense of energetic urgency. The film follows Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves, in prime form), a hotshot LAPD bomb squad member who recently succeeded in thwarting an elevator bombing by an aggrieved terrorist (an amped-up Dennis Hopper). As an act of revenge, Hopper’s bomber rigs a Santa Monica city bus to explode if his monetary demands are not met. If the bus accelerates over 50 miles per hour, the bomb will be activated. If the bus subsequently slows below this 50 mph threshold, it will explode. If the LAPD tries to remove the passengers from the bus, it will explode. These are the conditions in which Jack must save the lives of the ordinary Angelenos who happen to board this doomed vehicle.

One of Speed’s many strengths is its casual evocation of the day-to-day lives of the bus riders, succinctly crafting dynamic characters who exemplify the diversity of the city in microcosm. The nervous Helen (Beth Grant), who will later panic in the face of this dangerous endeavor, mentions that she started riding the bus due to stress: “I just couldn’t handle the freeways anymore. I got so tense.” Self-proclaimed “yokel” Stephens (Alan Ruck) is the quintessential LA tourist, confused by the airport and the city’s insufficient networks of transportation. Annie, played by Sandra Bullock in her breakout role, receives an especially snappy characterization. Aside from some small essential details – her revoked license, and her attendance at the University of Arizona – the film is ultimately uninterested in an elaborate backstory that would bog down the pace. The viewer meets her in a moment of high stress: chasing down the city bus, coffee in one hand, cigarette in the other. From the smirking reaction of bus driver Sam (Hawthorne James), this is part of Annie’s everyday routine – it’s just another day on the LA bus lines.

Of course, such expertly staged metropolitan mundanity only carries any weight in contrast to the intensity of Speed, a picture that deliberately heightens its pace – and its performances – to match the playfully choreographed chaos. Dennis Hopper, eight years after David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), brings a similar villainous ferocity to his role as the bomber, whose boisterous bellowing and unpredictable fury provide a sublime foil to the stoic Jack Traven. Reeves, ice cold off his widely criticized performance in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1993), is a natural fit as the sharp, cool-as-a-cucumber Traven, further honing the action star persona he began crafting as early as Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break (1991). Paired with the nascent everywoman charisma of Bullock, our three leads make for a formidable trio, helping to smoothly execute the narrative norms and beats that Bordwell emphasizes.

Far from just a showcase for its stars’ well-honed personalities, Speed is also one of the definitive Los Angeles movies, a city symphony that presents obstacles and details only possible in the smog-covered city of Angels. “LA is one large place,” Stephens quips at one point, and the film eagerly makes use of this sprawling landscape. Los Angeles is built upon a complex network of freeways, a web that enables high-speed pursuits and the omnipresent threat of stultifying traffic jams. De Bont, who served as the cinematographer for fellow LA actioner Die Hard (1988) before making his directorial debut here, uses the idiosyncrasies of the city to the fullest, exploiting the narrative challenges presented by construction hazards, the inescapable visibility of hovering local news cameras, and the threat of ravenous reporters. By the time Jack and Annie send a subway car crashing onto Hollywood Boulevard, landing in front of delighted tourists at the Chinese Theatre, the film’s portrait of everyday LA slyly gives way to an ending only possible in the movies. Hooray for Hollywood, indeed.

In a decade that produced a surplus of high-octane action filmmaking – from the continued reign of Die Hard’s John McTiernan to the emergence of Michael Bay’s signature mayhem – Speed remains a high point of the era. In the introduction to The Way Hollywood Tells It, Bordwell offers a defense of his study of classical norms, conventions, and “ordinary” films, writing that the interrogation of these norms allows us to “better appreciate skill, daring, and emotional power on those rare occasions when we meet them.” On its thirtieth anniversary, de Bont’s picture remains one such occasion: a beacon of classical Hollywood craftsmanship and its enduring ability to thrill the spectator.