This essay on Vanishing Point is by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A new 4K DCP of Vanishing Point will be screened on Friday, July 12 in the Cinematheque’s regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free. Copies of Vanishing Point Forever by Robert M. Rubin will be on sale before and after the screening. To learn more about the book and the movie, listen to a new episode of our Cinematalk Podcast featuring special guest Robert M. Rubin!

By Josh Martin

Kowalski (Barry Newman), the enigmatic protagonist of Richard C. Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971), is a man of few words. He is stoic and direct, always acting on impulse and instinct. This ethos of simplicity is even reflected in his mononymous title: in a deleted scene with a hitchhiker played by European film star Charlotte Rampling, Kowalski insists that this moniker is his “first, last, and only” name. Suffice to say that Kowalski, who finds himself in an interstate chase with highway patrol officers as he drives from Colorado to California, spends little time explaining the psychological motivations of his actions. Instead, he leaves the mythologizing to Super Soul (Cleavon Little), a blind disc jockey whose program becomes a sort of Greek chorus for the film, narrating Kowalski’s travels by following a police scanner. Through his radio show, the garrulous Super Soul molds the impenetrable Kowalski into a folk legend, a stand-in for the mood of America. Super Soul becomes the voice of Vanishing Point, anointing Kowalski as “the last American hero, to whom speed means freedom of the soul.” “The question is not when he’s gonna stop,” Super Soul wonders aloud, but “who is gonna stop him?”

If this seems rather philosophical for a car chase movie, it all functions harmoniously within Vanishing Point, which is described by cultural critic John Beck “as the apotheosis of the Vietnam-era exploitation/arthouse existentialist road movies produced in the wake of Easy Rider.” Sarafian, who rose in the ranks from industrial films to Hollywood alongside maverick director Robert Altman, indulges in the experimental spirit of the times. Inflected by Michelangelo Antonoini and other European arthouse masters, the film tinkers with temporality, narrative, and ambitious feats of montage, complicating its own straight-forward conceit. With a script written by Cuban novelist Guillermo Infante Cabrera (under the pseudonym Guillermo Cain), the film strives to probe the notion of the American spirit – to shape a portrait of the independent outsider whose resistance to conformity makes him a national icon and source of identification.

Yet far from a singularly intellectual exercise, Vanishing Point uses its sense of formal play to up the ante on its muscular thrills, balancing its competing aims as a State of the Union address and a super-sized stunt showcase. It is this tension – between the melancholic and the thrilling, the thoughtful mood and the high-octane jolts of action – that makes Vanishing Point so distinct. The plot, of course, is simple: late on a Friday night, Kowalski is assigned to deliver a Dodge Challenger to San Francisco. An amphetamine user and a compulsive risk-taker, Kowalski meets his drug dealer prior to the drive and makes a bet that he can complete the drive by 3 PM on Saturday. Such a feat, of course, would require Kowalski to drive extraordinarily fast.

And drive fast he does. In a quote from an interview with Turner Classic Movies that circulated widely upon Sarafian’s passing in 2013, the late director emphasizes his aim to “physicalize speed,” to make this experience palpable for the spectator throughout Vanishing Point. In the film’s initial chase sequence – which commences when Kowalski is spotted speeding by patrol officers – Sarafian initiates a bombardment of aggressive formal techniques. As Kowalski zips through this windy terrain, the camera presents hazy close-ups of the Challenger that soon shift out of focus, drifting into a blur of indistinguishable movement. The scene proceeds almost as a premonition of the style that would later develop in music videos, with electrifying editing rhythms and an underlying soundtrack of sonically aggressive rock music. If “[physicalizing] speed” was the principal goal, this exhilarating exercise is a testament to a job well done.

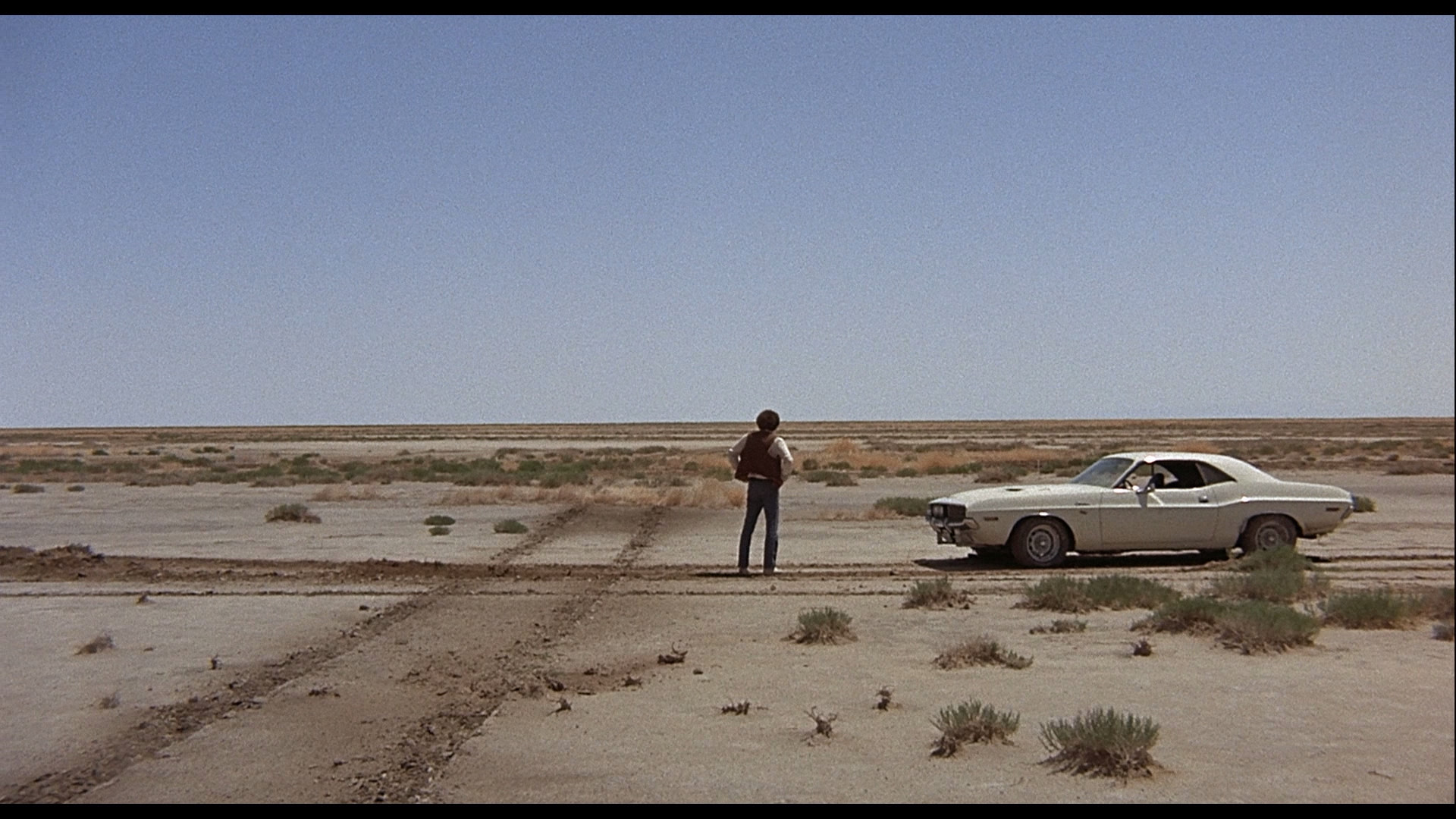

In the passages between these sensorial vehicular thrills, Vanishing Point emerges as a character study – of a character who refuses to be studied. Despite Kowalski’s reticence to speak and the overall narrative minimalism, the film continually discloses brief glimpses of exposition through elliptical editing, interrupting the flow of action to chronicle his life’s story. Throughout these fragments, the viewer sees the defining moments of Kowalski’s life: a near-fatal crash during a stock car race, his intervention as a cop during the sexual assault of a young woman by a fellow officer, and the death of his lover in a surfing accident. Later, the cops will discover Kowalski’s war history, adding another traumatic experience onto his growing record. With a life immersed in tragedy, Kowalski takes shape as a man more at home weaving through the verdant green trees and dusty desert landscapes of western America than continuing onward in traditional society. Though the film will pivot to a more literal death drive as its speedy journey progresses, Vanishing Point’s signature images of this outsider indulge in stunning natural scenery, prioritizing extreme long shots of Kowalski’s Challenger as a dot on the horizon, a blip on the expansive landscape around him.

In a rite of passage for every future cult classic, initial reviews in the mainstream press were far from kind. The New York Times’ Roger Greenspun derisively framed it as a film that asks the question, “why not make a dumb movie that is nothing but an automobile chase?” Yet half a century later, Vanishing Point remains a cultural touchstone – and an object of great interest to film directors and historians. Recently, Robert M. Rubin published Vanishing Point Forever (FilmDesk Books, 2024), a mammoth, 500-page volume that assembles production documents, marketing materials, and essays from critics such as J. Hoberman, all serving as proof of the idiosyncratic film’s enduring popularity.

The legacy of Vanishing Point extends to a widely discussed association with the work of Quentin Tarantino, who references the film in his 2007 exploitation homage Death Proof. As Tarantino’s quintessentially loquacious characters chat at a Tennessee diner, New Zealand daredevil and stuntwoman Zoe (Zoe Bell) professes her desire to drive a 1970 white Dodge Challenger, with her friend instantly exclaiming “Kowalski!” in return. When another character expresses their unfamiliarity with Vanishing Point, Zoe responds incredulously: “It’s just one of the best American movies ever made!” If it’s not one of the best American movies ever made, it certainly is one of the most American, channeling the spirit of the era and the sublime pleasure of its scenery to craft a portrait of the last American hero, “that last beautiful free soul on the planet.”