Godard's PHONY WARS: A Cinematic Palimpsest

TRAILER OF A FILM THAT WILL NEVER EXIST: PHONY WARS

The following notes on Jean-Luc Godard's Trailer of a Film That Will Never Exist: “Phony Wars” were written by Pate Duncan, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. Godard's final work, Phony Wars will be screened at 7 p.m. in the Cinematheque on Saturday, March 30, just prior to a 7:30 p.m. screening of Godard's Alphaville, showing in a new 4K DCP restoration. The screenings will be held in the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is Free!

By Pate Duncan

In his 1985 book Narration in the Fiction Film, the late film scholar David Bordwell described French iconoclast Jean-Luc Godard as having a “palimpsest” style. For Bordwell, Godard seemed to overwrite norms, conventions, and stylistic parameters on top of each other at different moments in the film’s production the way you or I might write out a grocery list on top of a receipt. It seems fitting, then, that Godard’s final film, Trailer of a Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars, released posthumously in 2023, is composed entirely of a series of static collages and palimpsests. The title itself pulls us in two directions, opening and foreclosing possibilities: it is both an anticipatory suggestion of what might be and an assurance of what will never come. Godard, famous in his early career for the prominent placement of consumerist French and American advertisements in his mise-en-scène, gives us one final advertisement—produced by French couturier Yves Saint Laurent, no less—with no accompanying product to buy.

Phony Wars is the last work in a diverse corpus of films, the likes of which we will never see again in cinema. Cinephiles will certainly recall Godard’s early period of films during the 1960s, a set of stylish, cool works like Breathless (1960), Vivre sa vie (1962), and Alphaville (1965) that boast formal experimentation over the material of Hollywood genre filmmaking and 1960s French consumer culture. In line with his status as a member of the left-wing French intelligentsia and interested in Marxism and semiotics, Godard’s works gave way to more political films like La Chinoise (1967), Weekend (1967), and Le Gai savoir (1969) before Godard moved into his Maoist period. During this more militant time, Godard partnered with Jean-Pierre Gorin to organize the filmmaking collective Dziga Vertov Group, named after the pseudonymous Soviet filmmaker and theorist. The most famous collaboration between Godard and Gorin is Tout va bien (1972), a Jane Fonda and Yves Montand vehicle that pulls equally from Jerry Lewis’s The Ladies Man (1960) and Bertolt Brecht’s separation of elements to show the events surrounding a strike in a dollhouse-like abattoir.

Godard’s films become increasingly puzzling after the mid-1970s, perhaps in an attempt to stand out from the younger crop of arthouse auteurs coming up around the same time. Films like Numéro Deux (1975), Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), Prénom Carmen (1983), Hail Mary (1985), and King Lear (1985) see Godard jettison the radical polemics in the film’s material while moving ever forward with his project of parametric film style. This period stretches the viewer’s capacity for narrative comprehension and remains esoteric in comparison to his ‘60s works (though these films are no less enjoyable than their more populist counterparts, at least amongst connoisseurs of Godard). In the 90s, we see the beginning of an era that might be described as late-period Godard, an era that includes the eclectic Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998), the fitful Film Socialisme (2010), the dizzying 3D Goodbye to Language (2014), and the revolutionary and hyper-saturated The Image Book (2018). The Godard of this period remained ruthlessly critical of the contemporary cultural and geopolitical order, impishly experimental in his film style, off-beat in his sense of humor, and iconoclastic to the last breath. These works alternatingly fascinate and frustrate even the most dyed-in-wool Godard fans, both Letterboxd hobbyists and tenured academics alike.

Late Godard is likely to confound viewers longing for the yé-yé needle drops, unexpected dance sequences, red-white-yellow-blue pop colors, and self-consciously cartoonish French sensibility of his ‘60s films. That is to Godard’s credit: unlike his peers of a certain prestige, Godard neither tried to return to his early appeal nor phoned these films in. Even minor works feel like something you’ve never seen before, challenge your viewing skills and patience in equal measure, and evince a deep love for what cinema can do at its extremes.

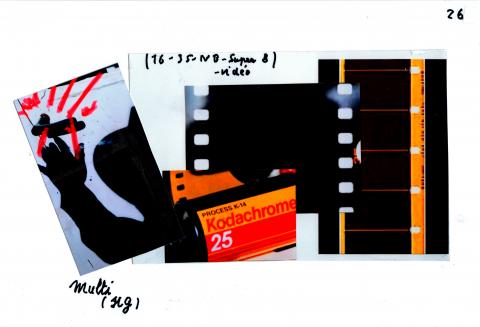

Phony Wars is the only of Godard’s films to be late style in both senses of the word: besides coming far into an illustrious career, it is his only posthumous release. We get a series of disparate still images, including an early image of red paint, tactile with impasto, scrawled over black. One is reminded of Godard’s famous quip that the excessive blood in his cinema is not blood, but red, that Godard’s excessive formal concerns should point us towards the graphic qualities of his works and not always or only to the real-life material they defamiliarize. It makes sense that Godard’s final moving images (in line with the fixations of his late style) are a series of photographs ordered in succession. We see mannered cursive handwriting spelling out quotes, witticisms, aphorisms, and even individual words struck through or covered over, often offset or accompanied by images of all stripes. We see paintings with artificially increased contrasts, Godard’s iPhone selfies, pictures of strangers and faces in such poor definition as to become uncanny. Fragments of sound are affixed to these curated collages, a few stingers of foreboding strings here, a few lines of speech there. Godard’s militant concerns rupture throughout, anchoring his aesthetic flights in a materialist sense of history. Under a repeat of the blood-red paint, we hear a politically prescient and timely line towards the end of the film: “Why Sarajevo? Because of Palestine, because I live in Tel Aviv. I want to see a place where reconciliation seems possible.” The extent to which Godard’s style or politics cohere into anything unified here is dubious, but to seek such coherence is to miss the point entirely: Godard, favoring process over product, prompts us towards politically engaged spectatorial experience, not a static or complete politics. Ekphrasis or visual description cannot do justice to the simultaneity of Phony Wars, cannot recreate verbally the complex push and pull that Godard’s palimpsestic style creates.

Kristin Thompson’s writing on Godard’s Sauve qui peut (la vie) in her 1988 book Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis refers to a different film and a different context, but her description gives us a certain truism to Godard’s work that brings Phony Wars into a different light: “Few, if any, filmmakers have so resolutely refused to settle into one approach; Godard’s experimentation has continued throughout his career [...] There is no one familiar Godardian landscape, though each of us may have a favorite work; the appearance of a new Godard film consistently holds out the promise of taking us unto unknown country” (288). Phony Wars gives us a number of “unknown countr[ies]” to ponder, be it the film itself as a final formal novelty, the nonexistent film for which it serves as a trailer, or perhaps what Shakespeare called “the dread of something after death/The undiscovered country from whose bourn/No traveler returns.” Whatever unknown Phony Wars conjures, it is undoubtedly a fitting swan song for one of the cinema’s finest artists.