Corruption Under the Rainbow: Fassbinder's LOLA

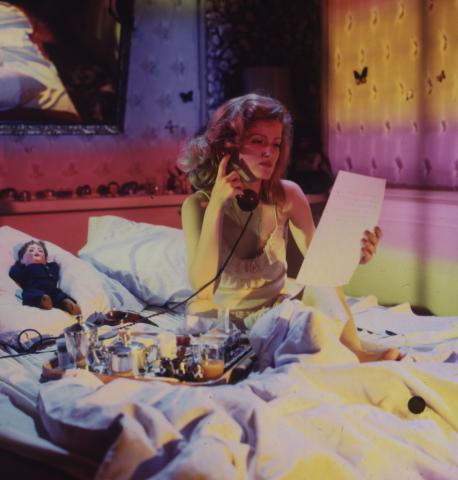

Barbara Sukowa in LOLA

These notes on Fassbinder's Lola (1981) were written by Tim Brayton, PhD candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A 35mm print of Lola will screen in our Sunday Cinematheque at the Chazen Fassbinder series on Sunday, December 9 at 2 p.m. in the Chazen Museum of Art's Auditorium.

By Tim Brayton

The opening credits of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1981 Lola end with a title card displaying in the upper right corner, in bright pink, “Lola BRD 3.” If you’re confused where BRD 1 and BRD 2 went, don’t worry. It was only during the making of this film that Fassbinder realized that this story of economic reconstruction and corruption in post-World War II Germany, centered around a woman embodying the spirit of her age, was a perfect thematic match to his earlier The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979). And so it was that the director decided to make the duo into an after-the-fact trilogy about West Germany (AKA Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or “BRD”) reasserting itself from the rubble of war. Though since Lola took place in 1957, a full decade later than Maria Braun, it made sense to leave room for another story in between them. Thus did Maria Braun end up unofficially serving as BRD 1, with the as-yet unrealized BRD 2, Veronika Voss, coming in 1982 (this last film will be concluding the UW-Cinematheque’s Fassbinder series on Sunday, December 16).

Lola has long been the black sheep of the BRD Trilogy, enjoying neither Maria Braun’s extraordinary financial success nor Veronika Voss’s critical reputation. Even so, there’s quite a lot going on here. The story takes place in Coburg, a city lying almost right on the border separating West and East Germany, and this unstated fact lies at the heart of the film’s drama. In fact, Coburg is something of a lawless frontier town, where all the worst parts of the reconstructing West Germany are allowed to run free: seemingly every public official we’ll ever meet is hopelessly corrupt, and they all congregate at the town nightclub/whorehouse, owned by a happily dissolute property developer named Schuckert (Mario Adorf). This is where we meet Lola (Barbara Sukowa), born Marie-Luise, a star cabaret singer.

Fassbinder chose 1957, and a plot centered around the politics of land development, to make a very pointed comment about what he considered to be the most amoral half-decade in post-war German history – and, of course, to comment about the reliable sordidness of human nature, a pet theme of his. One of the bleaker aspects of Lola is that literally every character we meet is in some way rotten, and somehow the worst of them all is also the most sternly moral. That would be Von Bohm, a refugee from the post-war expulsion of Germans from East Prussia, who has just come to the West to serve as Coburg’s building commissioner. He’s played, magnificently, by Armin Mueller-Stahl, himself a Prussian-born actor, and it’s easy to see in him a wary, unsmiling otherness in the face of all the jolly cosmopolitan hedonism of the rest of the cast. Unlike the other two films in the trilogy, which focus strictly on their leading women, Lola functions as a two-way character study, as Von Bohm inevitably falls in love with Lola. Sukowa and Mueller-Stahl are an exemplary mis-matched set, she bringing the theatricalized sarcasm we expect of a Fassbinder film, he remaining far colder and coiled up with the tension of a predatory animal. Both are wretches in their way, but the film seems to consider that at least Lola, like the rest of the West Germans, is honest in her depravity and greed, and so it finds a way into rooting for her against the priggish commissioner.

Fassbinder's Lola is based, unofficially, on Heinrich Mann’s 1905 novel Professor Unrat, and even more unofficially on that film’s iconic 1930 film adaptation The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola. It’s a far cry from the torrid Hollywood melodramas that had fueled most of Fassbinder’s work in the preceding decade, and perhaps that explains why Lola is so much more openly cynical than most of the director’s other major films. Still, it’s a characteristic Fassbinder exercise in worshipful cinephilia, and for all of its curdled psychology, Lola is an extraordinarily pleasurable movie, albeit ironic. It is among the most blatantly stylized of all the director’s films: as you will notice immediately, Lola is saturated with the most profoundly unnatural colors of some hallucinogenic rainbow. The film was shot by Xaver Schwarzenberger to mimic the bright saturation of Hollywood Technicolor cinematography, and the gap between the glowing colors of that style and the inherent brown grottiness of the film stock available in West Germany leaves Lola with a paradoxical beauty, both spectacular and toxic. It hardly needs saying that this visual aesthetic is a perfect match for a story about the corrupt heart underneath the bright and shiny face of a rebuilt midcentury Germany.

For all the nauseous greens and yellows, though, color in Lola is ultimately used to define the characters, and the destructive eroticism between Lola and Von Bohm. Throughout the movie, Lola is defined by shades of hot red: pink text in the opening credits, a cherry red stage for her singing, a scorching red sports car, red lighting practically everywhere. Von Bohm is defined, less aggressively, by cool blues and teals, especially the shockingly strong, almost glowing blue of his eyes, carefully lit to seem supernaturally oversaturated. These colors come into visual conflict with each other constantly, in all defiance of anything resembling realism: at one point, the two characters sit in a convertible that has been almost perfectly split in half between red and blue lighting, without even a glance at plausible motivation. They’re not the only contrasting colors here, either: the film’s color design perversely thrives on irreconcilable patterns of colors that the human eye can’t physically handle, giving the entire film an aggressive charge solely through its visuals. This expressionistic use of color, turning the characters’ inner lives into bold images, is startling, gorgeous, uncomfortable: it exaggerates the sumptuous cinematic pleasure of rich color into something so overindulgent as to feel rotten with decadence. Of all Fassbinder’s sardonic attacks on bourgeois culture throughout his career, this final assault on cinematic beauty itself just might be the most savage.