These notes on Raoul Walsh's Wild Girl were written by Casey Long, PhD candidate in UW Madison’s Department of Communication Arts. A 35mm print of Wild Girl from the Museum of Modern Art will screen in our Fox Restorations from MoMA series on Saturday, February 18 at 7 p.m., followed at 8:30 p.m. by a 35mm print of Walsh's The Yellow Ticket (1931).

By Casey Long

Director and actor Peter Bogdanovich kept a movie card-file from 1952 through 1970 in which he preserved notes and impressions on the films he viewed. When reviewing his screening notes for an article entitled ‘The Golden Age of American Talkies: 1932’, he discovered his 1966 card for Wild Girl. It read: “Beautifully photographed and robustly directed adventure set in the West, centering around a backwoods girl, delightfully played by Joan Bennett, and her dealings with several men: a good-hearted gambler, a hypocritical, lecherous politician, a two-faced rancher, and a young stranger who fought with [Gen. Robert E.] Lee and has come to kill the politician because he wronged his sister. The location shooting much improves the film, and Walsh’s unpretentious handling, speedy pace and sense of humor—as shown in the amusing stage-driver Eugene Pallette scenes—keeps things going even when the script bogs down in plots and sub-plots.”

Indeed, 1932 was a notable (or, “golden”) year for the industry. Many directors who would later become established contributors to the classical Hollywood canon made—not one—but several great films in that short time. Ernst Lubitsch did Trouble in Paradise and One Hour With You; Howard Hawks made Scarface, Tiger Shark, and The Crowd Roars; Josef von Sternberg filmed Blonde Venus and Shanghai Express; Frank Borzage made A Farewell to Arms and After Tomorrow; and the list goes on, including films by George Cukor, Allan Dwan, John Ford, Leo McCarey, Cecil B. DeMille, and King Vidor. Among the prolific filmmakers of 1932 was Raoul Walsh, who made two significant works in that year: the Joan Bennett/Spencer Tracy rom-com, Me and My Gal, and its near-immediate predecessor, Wild Girl, which paired Walsh with Bennett again and replaced Tracy with Charles Farrell as the romantic lead. Walsh, previously an actor himself, came to exclusively direct after a car crash led to the loss of his right eye during the 1928 filming of Sadie Thompson. His career rose to new heights after moving to Warner Bros. in the late 1930s, where he would direct such films as The Roaring Twenties (1939), They Drive By Night (1940), The Strawberry Blonde (1941) and White Heat (1949). Often regarded as a filmmaker’s filmmaker, Walsh’s films are known to move quickly from start to finish, without a dull moment. When asked what he considered to be the three greatest virtues of a film, he famously replied: “Action, action, and then action.”

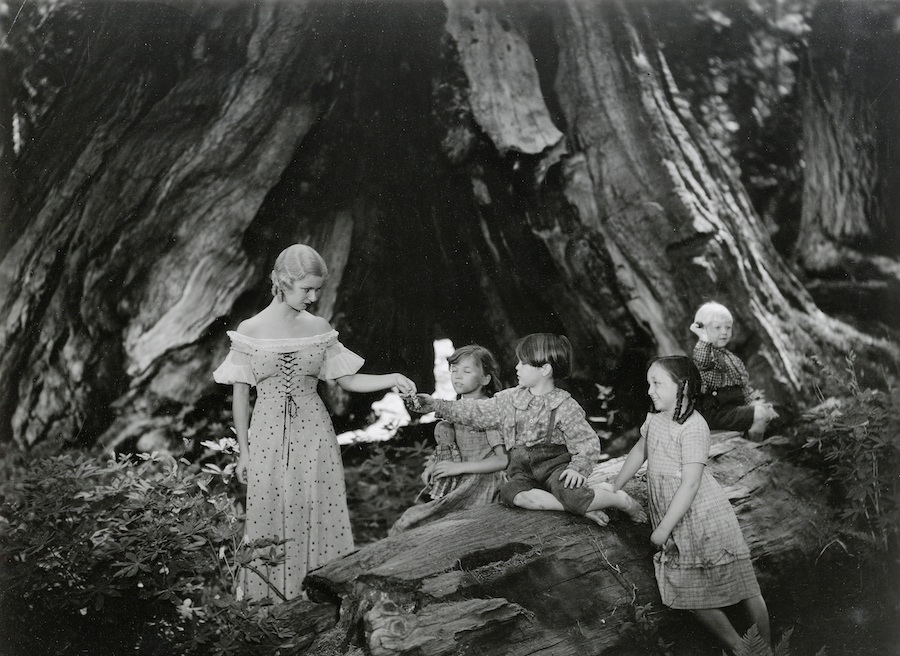

As Bogdanovich also notes, the film was primarily shot on location— in California’s Sequoia National Park. Several reviewers have pointed to the picturesque landscapes and naturalistic setting as a highpoint of the film— imagery that would be nearly impossible for cinematographers and set designers to recreate on the studio lot. It is really no wonder that so many have noted the beauty of Wild Girl— the cinematographer, Norbert Brodine, began his career as a WWI photographer and would later acquire a reputation as an ‘outdoor cameraman,’ praised for his black-and-white location shooting on films such as the film noir, Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1949). Of course, location shooting can have its downsides as well. Sally Gainsborough, a correspondent for Picturegoer magazine, was present for filming in August of 1932 and recounted the difficulties of shooting on location in the ‘High Sierras’: “one of the electricians [on set] described how a bear got into a garbage can during the night and scared him and his fellows almost to death!” And, later during filming: “…rangers soon have their hands full stopping all cars. It looks as if everyone in Central California has come to the park to-day… Suddenly in the middle of a love scene a distant car squeaks its horn. ‘Cut!’ The whole scene has to be done over again.”

The wilderness setting lends certain scenes with what one reviewer deems a “fairy-tale feel,” and also provides a loose motivation for Joan Bennett to perform in a nude lake swimming scene. This was, after all, pre-code Hollywood! Such arguably risqué behavior in American cinema would come to a swift halt only after the establishment of the Production Code Administration, which began censoring films released on or after July 1, 1934. Prior to this date, the flouting of the production code’s suggested ‘principles and applications’ was a well-known secret in the industry, since initial oversight (by Jason Joy and, later, James Wingate) was ineffective and the concurrent slump in ticket sales called for more scandalous content to boost attendance.

The source material for the film certainly does seem ideal for prodding or even mocking the pre-code censors. The lead character, Salomy Jane, is a non-conforming tomboy and the narrative’s major inciting incident is a Purity League member (and mayoral candidate) making a pass at her in a stagecoach. The screenplay was based on the short story "Salomy Jane's Kiss" by Bret Harte included in Stories of Light and Shadow (1898), his novel Salomy Jane (1910) and the play of the same name by Paul Armstrong (1907). From the AFI catalogue: “A [Hollywood Reporter] news item indicates that a working title for this film was Salomy Jane. Other films based on the Bret Harte story include the 1914 independent film Salomy Jane, starring Beatriz Michelena and House Peters; the 1923 Famous Players-Lasky Corp. film, also entitled Salomy Jane, directed by George Melford and starring Jacqueline Logan and George Fawcett; and the 1938 Twentieth Century-Fox film Arizona Wildcat.”