The following notes on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A special edition of Pat Garrett, created for the movie’s 50th anniversary in 2023, will screen in a 4K DCP on Saturday, March 22, the final film in our centennial tribute to director Sam Peckinpah. The screening begins at 7 p.m. at 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Josh Martin

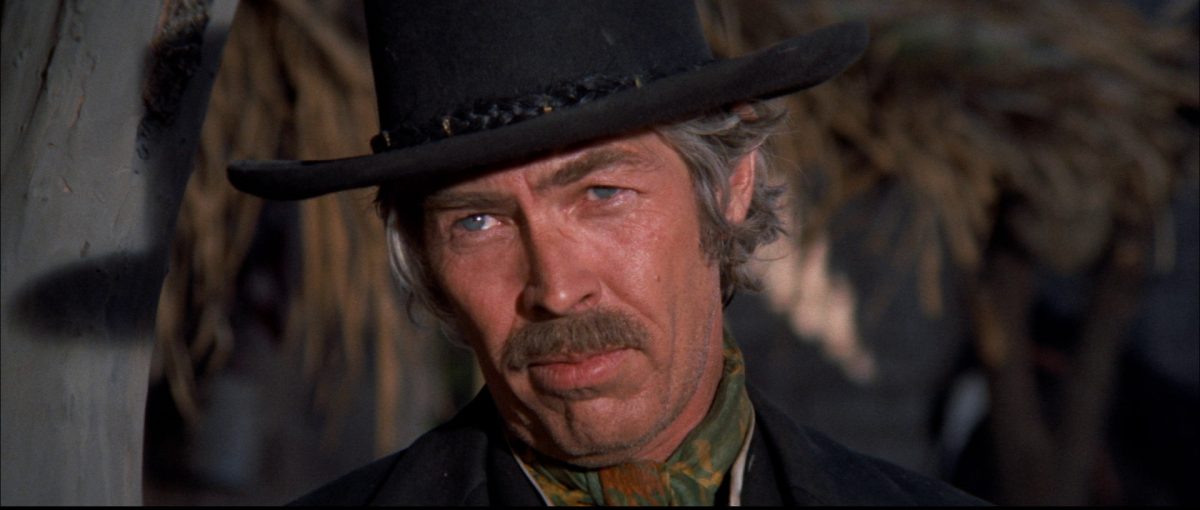

Early in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), our titular icons – Sheriff Garrett (James Coburn) and his friend-turned-foe William Bonney (Kris Kristofferson) – sit down for a drink in Old Fort Sumner, New Mexico. The year is 1881, and “times have changed,” as Garrett plainly states, a reinvention of the American West brought about by rancher John Chisum and the encroachment of modern life into the once-wild frontier. An outlaw himself who has since been legitimized in this new society as an elected sheriff, Garrett has come to offer a final plea to Billy: leave New Mexico before he must take him in. The men share a mutual respect, but they appear to have reached a stubborn stalemate, a tacit understanding that this can only end in a ritual of bloodshed. Time moves on and Garrett with it, yet Billy refuses to be tamed, nor will he betray the alliances he has forged. “Why don’t you kill him?” one of Billy’s cronies asks. Billy can only respond with determined resignation: “Because he’s my friend.”

The horror of the inevitable hangs over Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, a film that, depending on which version you see, begins with a sepia tone prologue that acknowledges Garrett’s killing of Billy and then chronicles Pat’s own violent death in 1908. By the time Peckinpah takes us back nearly three decades, everyone in this story is a ghostly myth already, wandering the West while they wait for their own bloody end to arrive. The plot, which follows Garrett’s pursuit of the Kid through the New Mexico desert, is circular in nature, beginning and ending at the hallowed ground of Old Fort Sumner, the Kid’s ultimate death place. Pat Garrett is far removed from the macho bonding of The Wild Bunch (1969) or the sly humor of The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), despite all three films serving as reflections on a changing Western world (and a changing genre). Instead, Peckinpah’s last Western is a heavier tale, laced with a meandering sadness amplified by Bob Dylan’s contemplative musical score and vocals.

In a film fascinated by the fragmented mystique of cultural legends, it seems fitting that Peckinpah’s picture would obtain a mythological status of its own. A survey of responses from the era’s major writers upon the film’s release – Roger Ebert, Pauline Kael, Gene Siskel – reveals a consummate snapshot of collective critical indifference and befuddlement. Yet these reviews tell only half the tale: Peckinpah’s film was dogged by accusations of incompleteness from the get-go, with Ebert notably calling attention to the director’s claims of studio interference.

In the half-century since the film’s middling debut, numerous versions of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid have seen the light of day. Editor Paul Seydor’s essay and subsequent monograph on the film is a crucial chronicle of the fractious post-production – a process made messier by Peckinpah’s severe alcoholism at the time – as well as its eventual reconstruction. The theatrical version of Pat Garrett, which runs 106 minutes, was flatly rejected by Peckinpah, who claimed that MGM had recut the film and tarnished his original work. After the film’s initial release and failure, two separate preview versions – each “conceptually and practically never finished,” per Seydor – were discovered in the subsequent years, during which time Peckinpah passed away from heart failure. Thus, three cuts emerge: the longer preview cut, initially made available on home video by Turner in 1988; another, slightly shortened “Final” preview, which Peckinpah supposedly snatched from MGM; and the significantly truncated theatrical cut. Assessed together, Seydor argues that “the previews compromise Peckinpah’s artistry and style,” while the theatrical version sacrifices “his vision.”

Faced with a paucity of good options for a new cut of a film from a since-departed director, Seydor eventually devised a plan to create a “Special Edition” for the Warner Bros.’ 2005 DVD release, one which left the Turner cut intact but also re-edited key preview scenes into the theatrical edition. The work of finalizing Pat Garrett has continued for many years: in 2024, with Roger Spottiswoode (one of the six credited editors on Pat Garrett) joining Seydor for further edits, the team produced the 117-minute-long 50th Anniversary cut of the film, the version screening this evening at the Cinematheque.

In the midst of so many cuts, edits, and speculative revisions, one worries that the legend has eclipsed the text, that the film itself has become lost in the quixotic pursuit of a great auteur’s unattainable vision. However, the wide availability of three of the various cuts, released by the Criterion Collection last year, should close the book on the alluring mystique of what could have been. Though this turbulent production history will always be part of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid’s story, viewers can, at long last, meet the film on its own terms. Indeed, its bracing intensity cuts through the fog of alternate editions and possible amendments: it is a rendition of Peckinpah’s signature musings drained of any vengeful exhilaration or pleasure, where one era’s dusk and another’s dawn is a downbeat experience, clouded by the omnipresence of death and the violent fissure of once-vital relationships.

Such a dissolution of the Wild West grows more pronounced in the film’s second half. As Pat Garrett finally reaches its preordained confrontation between its central characters, Peckinpah shifts into an even slower, more haunting register. The mood at nocturnal Old Fort Sumner grows silent and pregnant with anticipation. Garrett’s movements are sluggish; he seems to abhor his pursuit, even sitting down on a rocking porch swing, emotionally hollowed out by the hunt. Garrett is saddled with the weight of finality, the knowledge that he cannot change the path that brought him here – or lessen the impact of murdering the Kid on his soul.

It is an emotional gravity that defines Peckinpah’s farewell to the genre. In perhaps the most enduring moment of the picture, a bloodied Sheriff Colin Baker (Slim Pickens), shot while aiding Garrett, sits down by a riverbank. As Baker comes to terms with his own impending death, Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” a tragic yet soothing meditation on mortality (and a music cue that, per Seydor and Kristofferson, Peckinpah did not want), enters the soundscape. “Mama take this badge off of me, I can’t use it anymore” Dylan croons, “It’s getting dark, too dark to see.” With tears in her eyes, Baker’s wife (Katy Jurado) crouches by the shore near him, while Garrett can only watch this unbearably sad scene from afar. In this one tableau exists the core of the film’s dying world, a portrait of men accepting the end as they find themselves knockin’ on heaven’s door.