These notes on Edgar G. Ulmer's The Black Cat (1934) were written by Luke Holmaas, PhD candidate in UW-Madison’s Department of Communication Arts. A 35mm print of The Black Cat will screen in our Sunday Cinematheque at the Chazen "It's a Universal Picture" series on Sunday, March 3, at 2 p.m. in the Chazen Museum of Art.

By Luke Holmaas

The Black Cat is a film that stands as a study in contrasts. Among other things, the film is notable today for being the first of eight pairings of horror stars Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi and for Heinz Roemheld's influential, near-constant score. An anomalous foray into major studio production (albeit at the mini-major studio Universal) for legendary B-movie auteur Edgar G. Ulmer, The Black Cat was also an anomaly within the context of Universal’s famed 1930s horror productions. Although made on a shorter shooting schedule (a mere fifteen days) and for a $91,000 budget that amounted to only one-third and one-quarter the amount allocated to the earlier Universal classics Frankenstein (1931) and Dracula (1931) respectively, The Black Cat was a major financial success for the studio. It wound up as Universal’s biggest box office hit of 1934 in spite of both its extremely tenuous connection to the Edgar Allen Poe story of the same name (Ulmer confirms that the Poe connection was kept simply to draw interest to the film) and decidedly mixed reviews. The Hollywood Reporter characterized it as lacking thrills as Karloff and Lugosi “fight it out … for the mugging championship of the picture," while the San Francisco Examiner praised it as “the most cultured horror film” they had ever seen. Nevertheless, bad blood between studio head Carl Laemmle, Sr. and Ulmer developed over the film’s atypical use of music, and was soon to be exacerbated by Ulmer's affair with Shirley Alexander, the wife of Laemmle's beloved nephew Max. This meant that Ulmer would never receive a chance to follow up on the film's success at Universal, instead being “exiled” to the world of low-to-no budget Yiddish films and Poverty Row quickies for which he would later be best known.

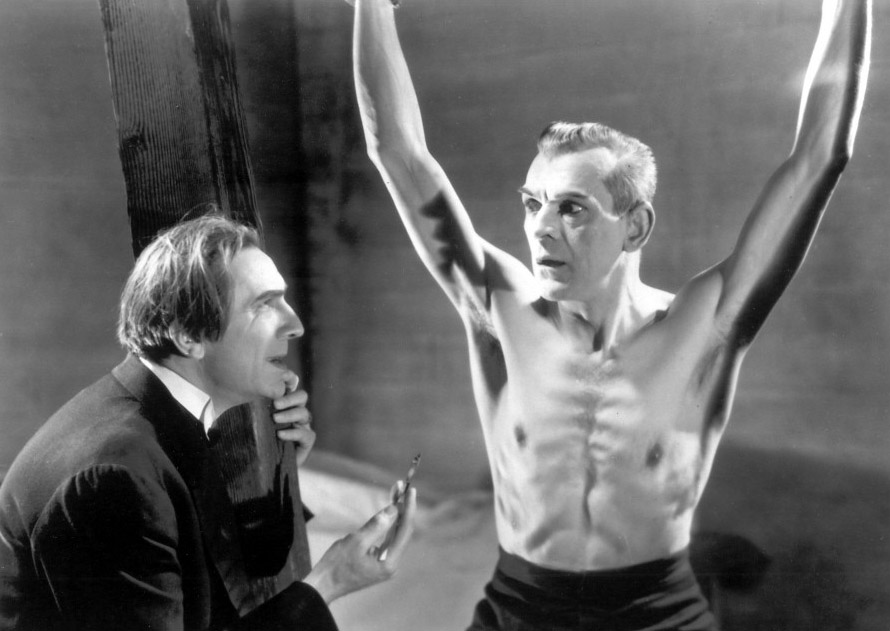

While the idea of Ulmer continuing to work for major studios offers a tantalizing alternate history, what The Black Cat does provide us with is a singular film in its own right: a dreamlike, metaphysical, horror-thriller that blends early twentieth-century European avant-garde design with odd flourishes of campy humor, refined perversion, and unsettling brutality. The film’s story seems eerily like the plight of contemporaneous American audiences encountering the film for the first time: an American couple, Peter Alison (David Manners) and his new wife Joan (Julie Bishop), encounter war-scarred psychiatrist Dr. Werdegast (Lugosi), who is seeking revenge on Satan-worshiping war criminal Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff) in his Hungarian castle. Drenched in continental European culture, from the Expressionist and Bauhaus-inspired designs within Poelzig’s castle to the strains of Brahms, Bach, Liszt, and Schubert (among others) on the soundtrack, The Black Cat also offers a rare glimpse of a Hollywood horror film deeply invested in the traumatic aftermath of World War I. The story, with the lingering traumatic effects on the lives of the war's survivors (both Werdegast and Poelzig) and the stark and striking production design (that looks back to the immediate postwar German avant-garde and also forward to the fascist architecture of World War II Germany) work together to keep the war’s legacy in our minds.

The film’s striking artistic achievement and unique atmosphere is due in no small part to the contributions of numerous European-inspired artists. From the Old World charms of the British Karloff and the Hungarian Lugosi to the contributions by British-born art director Charles D. Hall and the Milwaukee-born, but Berlin-educated, composer Heinz Roemheld, The Black Cat offers a perfect mixture of lurid American and refined European horror. And although contemporary reviewers were often more likely to dismiss the film as unsatisfying in the horror department (with Picture Play Magazine declaring the film to contain no terror, not even in the film’s climactic flaying scene), The Black Cat has continued to cast its uniquely unsettling mood for audiences in the decades since. The cable channel Bravo named the aforementioned flaying scene as one its “100 Scariest Movie Moments” in 2013 and film critic J. Hoberman made the memorable assertion that the film connects Germanic culture “from Caligari to Hitler in one lurid package" (a reference to Siegfried Kracauer's groundbreaking 1947 study of interwar German film and its impact on society). A beguiling fever dream of horror, war, and art, The Black Cat still manages to create a unique thrall for all those who fall under its spell.