The following notes on Capricorn One were written by Sarah Mae Fleming, PhD candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW – Madison. Capricorn One screens at the Cinematheque’s regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave, on Saturday, January 31 at 7 p.m. Admission is free!

By Sarah Mae Fleming

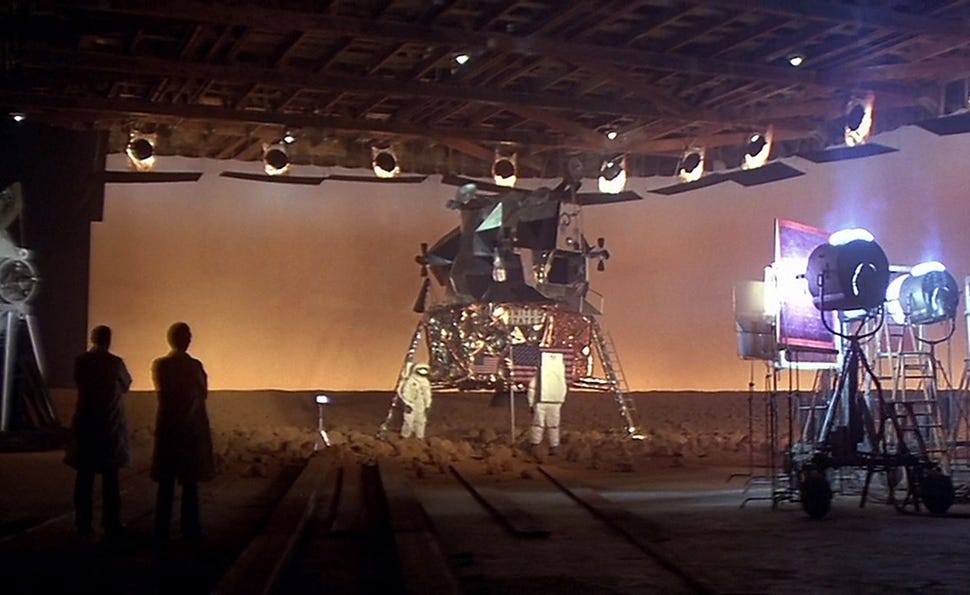

By 1977, American audiences had learned to recognize the shape of a conspiracy: the skeptical editor, the dogged reporter, and the institutional cover-up slowly coming apart. The Watergate scandal and its imprint on subsequent cinematic thrillers had turned these tropes into reliable narrative patterns. In Peter Hyams’s Capricorn One, reporter Bob Caufield (played by a harried Elliot Gould) badgers his editor into taking his hunch seriously by quoting the tough-talking editors of other journalism movies, then ends his outburst with: “That’s what he’s supposed to say—I saw it in a movie.” Hyams knows his audience has seen those movies too, and he’s happy to give them another paranoid thriller in that vein. But the conspiracy at the center of Capricorn One involves something a bit more reflexive: a government conspiracy, manufactured entirely on a soundstage with cameras, lights, and careful compositions. The film does not exactly deconstruct the thriller formula, as it’s far too busy enjoying it, but there is something pointed about making a movie where the conspiracy is itself a movie. What happens when the technology used to deceive the world is the same technology we use to understand it?

Set against the backdrop of a highly publicized mission to Mars, Capricorn One follows three astronauts who are abruptly pulled from their spacecraft moments before launch. As the world watches the rocket depart, the men are secretly transported to a desert facility, where they are forced into an extraordinary deception designed to protect NASA’s public image and political survival. When things go wrong, the astronauts must flee for their lives while Gould’s doubting journalist begins to suspect that the triumphant broadcast he is watching is not what it seems.

Hyams developed the idea while working in television journalism for CBS in the late 1960s, helping cover NASA’s Apollo missions. Much of what viewers saw on the evening news came from studio-constructed simulations. Watching these recreations on the monitors, Hyams began to wonder how indistinguishable they were from reality. According to film historian Frederick C. Szebin, Hyams later recalled, “I was part of the generation that believed if it was on television, it was true.… Suppose you did a really good simulation?” With access to NASA manuals, schematics, and mission documentation through his reporting work, Hyams started writing a script about a space mission that only appears to be real. After the box office failure of Peeper (1975) left Hyams effectively unemployable in Hollywood, the director was rescued by his friend, producer Paul Lazarus, fresh off the success of his work on Westworld (Crichton, 1973) and the sequel Futureworld (Heffron, 1976). Lazarus took the script overseas to British mogul Sir Lew Grade (famous for backing ambitious international co-productions) and sold him on the premise with a single high-concept logline: a fake Mars landing in which NASA and the US government are the villains.

Grade agreed to option the story then committed fully after requesting only minimal changes. His strategy was to pre-sell the film internationally using an ensemble of recognizable but not top-tier stars: Gould, James Brolin, Sam Waterston, Karen Black, Brenda Vaccaro, and (chosen as much for financial leverage as for their performances) O.J. Simpson and Telly Savalas. Surprisingly, for a movie about government deception, the filmmakers received extraordinary cooperation from NASA itself. Thanks to Lazarus’s earlier relationship with the agency, the production was allowed to use an actual prototype landing capsule—saving enormous amounts of money and, at the same time, lending some of the most pivotal scenes a high production value. Lazarus later admitted he was stunned that the script had been approved at all.

Shot in 1977 on a modest $4.8 million budget, Capricorn One was made largely free of studio interference. The production staged elaborate aerial sequences involving helicopters pursuing a crop-duster plane, built special camera rigs to capture near-collisions in midair, and filmed desert survival scenes in the Mojave that look genuinely punishing. One of the film’s most notorious images shows astronaut Brubaker (Brolin) gnawing on what looks like a freshly killed rattlesnake. It was actually tuna sashimi, but the moment proved so unsettling that airlines later asked for it to be removed from in-flight screenings of the film. After production, trouble came with distribution as Warner Bros. initially planned to dump the film into a February release slot, seeing it as a minor action picture. Strong preview screenings (and the sudden delay of Richard Donner’s Superman, which left a prime summer opening vacant) promoted Capricorn One to a May release and allowed it to become the most successful independently financed film of the year.

The film’s most incisive media commentary arrives as Brubaker’s wife Kay (Vaccaro) shows Caulfield a home movie shot on a family vacation. Caulfield watches the Brubakers marvel at a Western being filmed, complete with cameras on cranes and stunt performers landing on hidden crash pads. Kay remembers how her husband “couldn’t believe how something so fake could look so real.” She recalls Brubaker remarking, “With that kind of technology you could convince people of almost anything.” As the projector’s flickering light washes across Gould’s face, he finally understands what the audience has been privy to all along: the Mars mission never really happened.

In Capricorn One, the hoax works (for a while) because it looks and sounds right: the sets are convincing, the camera placement hides the seams, and manipulation of the broadcast even mimics zero-gravity. Spectacle stands in for evidence. In 1977, audiences might have been anxious about network television and centralized government control dominating a single channel of information. In 2026, we are confronted with artificially generated images and synthetic voices capable of flooding platforms with fabrications faster than any centralized operation could manage. As we rely on audiovisual evidence as proof, realism is still a technology that can be used against us. Capricorn One may be an old-school thriller, but its central unease has only grown sharper: what happens when you can no longer tell whether what you’re seeing and hearing corresponds to anything happening in the world at all?