The following notes on Brazil were written by Lance St. Laurent, PhD candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW – Madison. A newly restored 4K DCP of Brazil, presented in the uncut, original European release version, will screen at the Cinematheque on Saturday, December 6, 7 p.m., 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Lance St. Laurent

Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) is as good as dead. In the process of taking charge of his life for the first time, the mild-mannered bureaucrat has drawn the ire of the same totalitarian regime he just days before called his employer. Strapped to a chair in a cavernous torture chamber, his life has been voided. All that’s left now is a painful end—that is, until a daring rescue from the literal woman of his dreams (Kim Greist) frees Sam from the clutches of his captors. Jackbooted thugs chase Sam through the city, but he and his lady love evade arrest. After driving through the night, they find refuge in an idyllic countryside cabin, far away from the urban misery of their former home. As Sam sleeps, content, he returns to his favorite dream, where he is a glittering warrior soaring through the sky, his fantasy woman on his arm. The dream has become reality. Sam is free. Roll credits.

Thus ends the so-called “Love Conquers All” cut of Terry Gilliam’s 1985 masterpiece Brazil. Commissioned by Universal chairman Sid Sheinberg, this cut made a mockery of Gilliam’s original vision, chopping it down to just over 90 minutes and saddling it with a perfunctory happy ending. While this cut was never released theatrically (Criterion included it as part of an extensive special edition decades later), it represents the lengths that Sheinberg and Universal were willing to go to assert control over Gilliam’s unruly opus. But what was it about Brazil that so troubled Sheinberg and the executives at Universal?

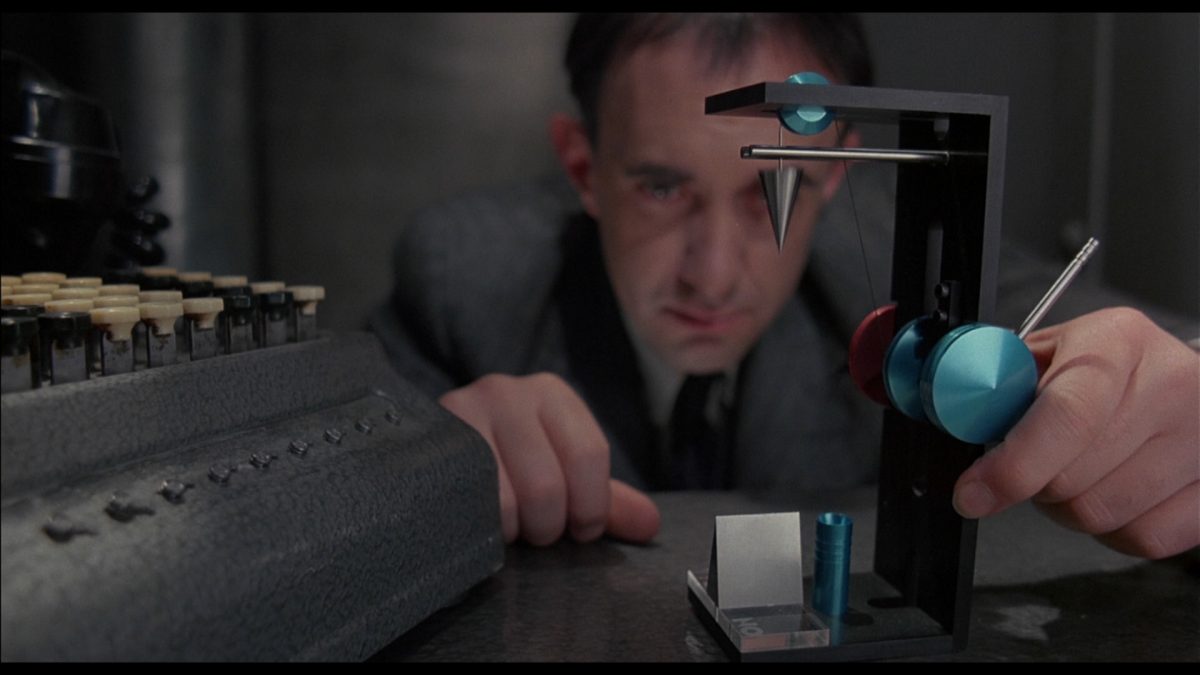

Like many other Gilliam films, Brazil is the story of a man fixated on fantasy and checked out of real life. Sam Lowry spends his days in hopelessly drab, cramped office spaces, dutifully crunching numbers on a tiny computer screen while letting his mind wander to a world where he can be a heroic figure of old, a knight rescuing a damsel from the same oppressive forces of industry and technology that bear down on him every day. However, Sam’s world of industrial drudgery is not our own. Instead, the world of Brazil is a nightmarish vision of future dystopia, fusing literary influences such as George Orwell and Franz Kafka with visual touchstones from German expressionism, Jacques Tati, and Gilliam’s own work as part of the Monty Python troupe. Collaborating on the script with Charles McKeown and an acclaimed playwright, the late Tom Stoppard, Gilliam envisioned a one-of-a-kind metropolis where gigantic looming skyscrapers are packed to the gills with impenetrable tangles of cables, tubes, pipes, and half-working machinery. Instead of centralized authority under the rule of Big Brother, Brazil posits a world being smothered by an arcane, impossible-to-navigate bureaucracy. Every possible municipal action requires a form, and every form must be filled out in triplicate before being stamped by a different department—no, not that department, actually another department—though it’s ultimately a different form you needed and it’s only available in yet another department, and they are out for lunch. Efficiency and responsibility are concepts that have died long ago, and the machinery of government, including violent home invasions, sudden arrests, and systemized torture, grinds on with seemingly no one in charge and very few who care.

Though the film is often outrageously funny, Brazil is also one of the most despairing films ever released by a major studio, a merciless odyssey through a senseless world. And though the film features performances from major stars like Robert De Niro, Ian Holm, Bob Hoskins, and Gilliam’s fellow Python Michael Palin, the actual lead of the film was Jonathan Pryce, an acclaimed but little-known character actor. The film was released overseas in its original form, but Universal, the film’s American distributor, became concerned. The studio delayed the release and quarreled with Gilliam behind the scenes, demanding significant edits and eventually creating the infamous alternate cut without Gilliam’s contribution for test screenings. The conflict became so intractable that Gilliam eventually took out a full-page ad in Variety imploring Sheinberg and Universal to release his film, prompting Sheinberg to respond with a countering ad offering to sell the film.

In a spirit of rebellion not unlike the one running through the film, Gilliam eventually staged secret, unsanctioned screenings for critics, leading to the film being awarded Best Picture by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Universal finally relented, releasing a slightly modified cut of the film overseen by Gilliam in 1985 to much acclaim, though minimal box office. Less than a decade later, a true director’s cut, restoring every minute of Gilliam’s original version, was released on LaserDisc and has subsequently become the canonical version for restorations and home video releases.

In the decades since its troubled release, Brazil has been cemented as Gilliam’s magnum opus and a Rosetta stone for the rest of his work. His later dystopias in 12 Monkeys (1995) and The Zero Theorem (2013) draw heavily from Brazil, while characters from The Fisher King (1991) and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) similarly give into flights of fantasy, though they are induced by madness and drug use. Gilliam even reunited with Jonathan Pryce to depict one of literature’s most enduring dreamers, Don Quixote, for his decades-in-the-works The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in 2018. Still, Brazil remains the most complete expression of Gilliam’s singular sensibility, which blends whimsical imagination with acidic cynicism in a combustible mixture that inspires awe, elation, and anguish in equal measure.