The following notes on The Great Dictator were written by Nick Sansone, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A 35mm print of The Great Dictator will screen at the Cinematheque on Saturday, November 8. Showtime is 7 p.m. at 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Nick Sansone

In 1940, decades into Charlie Chaplin’s career as one of cinema’s first true auteurs and comedic stars—and twelve years after the film industry fully embraced synchronized sound and dialogue—the multi-hyphenate star produced his first talking picture, The Great Dictator. Until this point, Chaplin had resisted significant pressure around him to stop making silent films, continuing to play his Little Tramp character without speaking in beloved classics such as City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936). When he resorted to sound, he did so only to mock it, such as in a late Modern Times scene where the spectator hears the Tramp singing a song with completely nonsensical lyrics. By the late 1930s, it was clear to Hollywood and contemporary audiences that Chaplin was only ever going to switch to talkies on his own terms. With The Great Dictator, Chaplin finally found the right material for this pivot, employing sound to provide a searingly urgent political statement about current events.

At the time of The Great Dictator’s release in the fall of 1940, Adolf Hitler had been the dictator of Nazi Germany for just under eight years, and the United States had not yet joined the Allied Forces of Britain and France in combatting the Nazis in World War II. And yet, in spite of the pervading isolationist sentiment in the U.S. at that time—a sentiment so strong that Franklin D. Roosevelt won a third term as President largely on a promise to not send the country into war—the film became a massive hit for Chaplin and the United Artists production company he co-founded, ending the year as the second-highest-grossing film (behind only MGM’s Boom Town). While Americans may not have been ready to go to war with Nazi Germany just yet, many knew full well the repressive actions of the Nazi regime in Germany, thus enabling Chaplin’s blistering critique and mockery of these heinous politics and Hitler’s dictatorial persona.

But rather than simply zeroing in on Hitler’s dictatorship and human rights abuses in Nazi Germany, Chaplin tapped into something much deeper and more personal in developing The Great Dictator. Ever since Hitler first came to power in Germany in 1933 and became an internationally known figure, many pointed out the physical similarities between he and Chaplin, most obviously their toothbrush mustaches. However, as Chaplin learned more about Hitler’s background and life leading up to his reign of terror in Europe, he realized just how similar their lives were before they diverged in such drastic and opposite ways. The two men were born exactly four days apart in 1889, both rising from impoverished backgrounds to obtain positions of prominence. Charles Chaplin, Jr. wrote extensively about this in his memoir My Father, Charlie Chaplin, noting that these similarities haunted his father and drove the scorching nature of the satirical critique of Hitler present in The Great Dictator. The concurrent trajectories of Chaplin and Hitler have been of interest to film historians as well, with Kevin Brownlow co-directing a short documentary—The Tramp and the Dictator—about Chaplin and Hitler’s parallel lives.

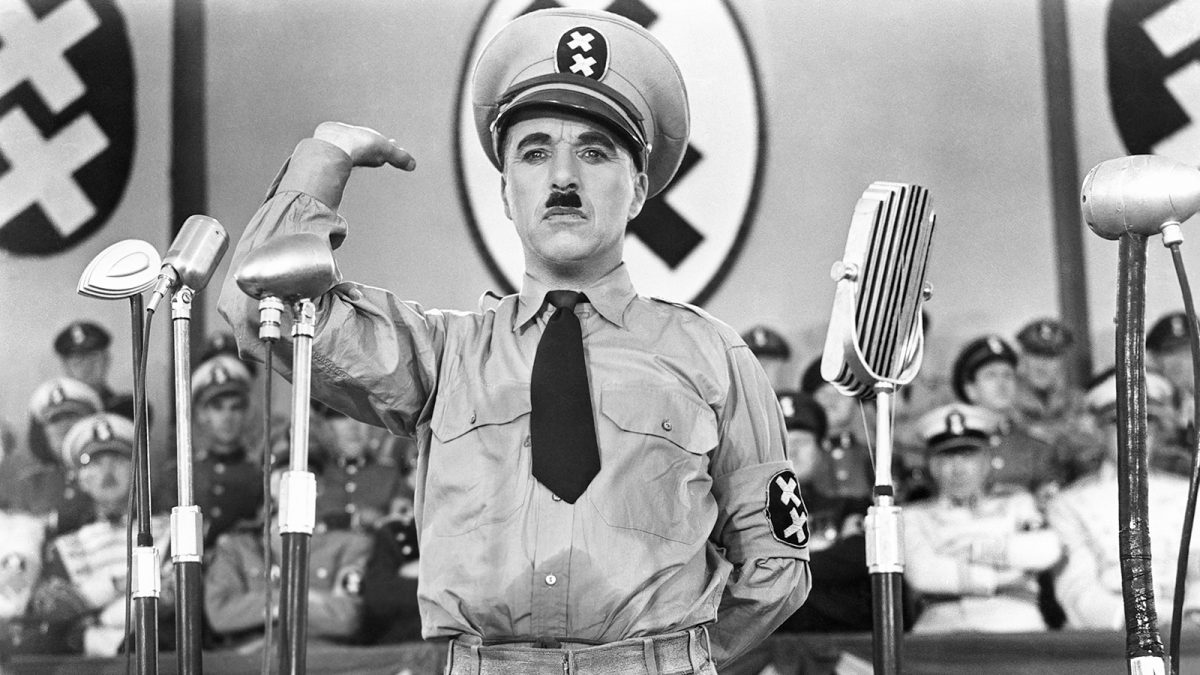

Working through these two key ideas—his hatred for Hitler’s monstrous and dangerous views and the disturbing knowledge of their similar backgrounds—Chaplin based The Great Dictator around two characters, both played by himself. The first, Adenoid Hynkel, is an intentionally ridiculous parody of Hitler who nonetheless embodies all of the German leader’s fascistic qualities, most specifically his hatred of the Jewish people. The second character is an unnamed Jewish barber who has more than a little in common with Chaplin’s earlier Tramp character. While Modern Times may have been Chaplin’s official send-off to the Tramp, the barber allowed Chaplin to explore similar comedic and thematic ground, including the return of a familiar co-star: his then-wife Paulette Goddard, who played the Tramp’s paramour in Modern Times, appears again here as Hannah, the barber’s love interest.

Although much of The Great Dictator draws a stark contrast between the barber and Hynkel, showing the latter repressing the former’s human rights and dignity, Chaplin very intentionally turns the tables by the film’s third act. Here, the classic comedic tropes of disguise and mistaken identity scramble the circumstances of our characters, building to what is arguably the film’s most famous moment: Chaplin’s concluding speech. While the entire film never shies away from the deeply serious nature of its underlying subject matter, Chaplin made sure absolutely no one in the audience missed his central message in the film’s fiery finale. At the start of the speech, Chaplin is still ostensibly playing the barber character in disguise as Adenoid Hynkel. Yet as Chaplin continues, it becomes abundantly clear that the star is speaking to the film’s viewers as himself, making an increasingly impassioned plea for democracy, unity, liberty, peace, and reason, urging viewers to reject brutes and dictators. Chaplin’s choice to end his film with a lengthy speech delivered to the camera has been debated by various critics and scholars over the years, but there is no denying the power and poignancy of his words—or the conviction with which he delivers them.

Following the film’s release and critical and commercial success (including five Oscar nominations), Chaplin’s career went into deep decline as he suffered legal troubles, public scandals, communist allegations during the Hollywood blacklist era, and ultimately a ban from entering the U.S. He only made four more feature films following The Great Dictator, including the reflexive and tragic Limelight (1952), his final film for United Artists, before his death in 1977. Now, 85 years after the film’s release, The Great Dictator — screening today on a 35mm print — continues to inspire and entertain audiences in the midst of rising authoritarian movements and governments throughout the world. Just within the last decade, both Coldplay and U2 have sampled clips from Chaplin’s final speech in their live stadium concerts, often positioning his words against contemporary news clips to illustrate the continued relevancy of his sentiments. For as long as any oppressive regimes or dictators exist anywhere in the world, Chaplin’s film and the words he speaks in it will continue to serve as a constant reminder for viewers to fight for unity and the good of all people.