HEIRONYMOUS MERKIN: A Musical Cinematic Phantasmagoria

This essay on Anthony Newley's Can Heironymous Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? was written by Cinematheque staff member Amanda McQueen. Part of our Musicals of 1969 series, a 35mm print of Can Heironymous Merkin...will screen on Friday, February 5, at 7 p.m. in the Cinematheque's main venue, 4070 Vilas Hall. Never before released on home video, this screening is an ultra-rare opportunity to see one of the era's wildest and most personal movies.

By Amanda McQueen

“You must read this review carefully. Every word of it. Yes, if you decide to run off and see Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? you are going to have to know what you are letting yourself in for.” So wrote the Chicago Tribune about Anthony Newley’s self-proclaimed “sexplicit” musical. Combining traditional show tunes with a Fellini-esque reflexivity and a surplus of nudity and bawdy humor, Merkin is indeed a very strange film. Merkin is also—as the Los Angeles Times noted—“a genuine document of its time,” tapping into nearly every contemporary cinematic and cultural fad. When else but in 1969 would a major studio produce an X-rated musical art film?

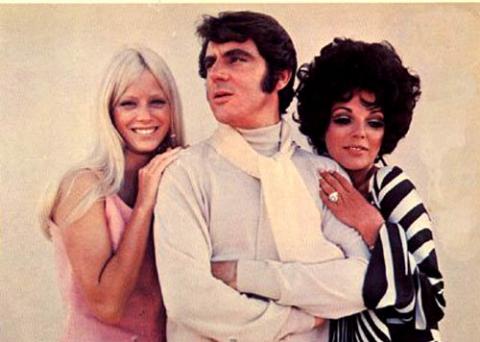

Newley came up with the idea for Merkin during down-time on the production of Doctor Dolittle (1967). “I would write down all I could remember about my life,” the English actor-singer-composer explained. “The ladies, the selfishness, the death of my first child. I decided this was going to be my movie. I would direct it and for once I’m the painter instead of one of the daubs of paint.” Newley also produced the film and starred as the titular Heironymus Merkin—an aging performer and womanizer reflecting on his life and legacy by making and watching a film about his life and legacy. He cast his own wife, Joan Collins, as Merkin’s wife, and his own children as Merkin’s children. He co-wrote the screenplay with Herman Raucher, and he composed the songs with lyricist Herbert Kretzmer (Les Miserables [1985]). In short, Merkin became Newley’s pseudo-autobiographical one-man show.

After some difficulty getting anyone interested in the project, Universal’s British arm agreed to co-produce and to distribute the film under its subsidiary, Regional Film, which, according to Variety, “handles product Universal doesn’t care to go out under its own banner.” The studio’s uncertainty was understandable. In Newley’s words, Merkin was a “modern musical with no plot, but very sexy, very funny and very serious.” Though not quite plot-less, it is an episodic, surreal, and telescoping film-within-a-film-within-a-film. Its characters are called Polyester Poontang (Collins), Good Time Eddie Filth (Milton Berle), and The Presence (George Jessel). It references everything from Ingmar Bergman to Rodgers and Hammerstein. It details Merkin’s obsession with the nymphette Mercy Humppe (Playboy Playmate Connie Kreski). It contains a suggestive song about a princess and a donkey. In short, Merkin was sexually explicit and arty—both factors that could limit its success with a general audience. Reportedly, though, Universal was more concerned about the musical’s “abstract and symbolic” elements than its “epidermis and erotica.” Hollywood's self-regulation of adult content had been relaxing for some time, and the MPAA would replace the Production Code with a rating system in November 1968. Sexy movies were in vogue; art cinema remained a niche market.

Budgeted at just over $1.25 million, Merkin went into production in March 1968 in Malta, where filming was inexpensive and scenic, but not without difficulties. The country was predominately Catholic, and a campaign was waged against Newley’s nudity-filled movie. Local authorities ultimately had to intervene to disperse protesters and allow shooting to continue. Upon its completion, Merkin was condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency and given an X rating by the MPAA—the sixth film to be so designated. (It was reclassified as R in 1972.)

In March 1969, Merkin had a profoundly disappointing premiere in New York City. Forty people walked out of the press preview, and the film was panned by many influential critics. The New York Times called it an “act of professional suicide.” Its box office performance was correspondingly “dismal.” But as Merkin made its way across the country that summer, it started to become a hit. Unlike many other X-rated films, Merkin encountered no grassroots censorship problems, and it played in many rural and suburban communities where X-rated films and hardcore pornography rarely screened. Variety hypothesized that the cast—Berle, Jessel, and particularly Newley, who was associated with family entertainment due to his musical theater work—had perhaps “softened” the film’s potentially offensive material, removing any “’dirty movie’ taint” for those “hinterland” audiences.

But industry insiders surmised that the true key to the musical’s success was its extensive advertising in Playboy Magazine, which had a strong influence on those under thirty and especially on those living outside major cities as “a source of mild titillation and tastemaker.” In March 1969, Playboy ran a ten-page spread on Merkin, emphasizing Connie Kreski's involvement. This was followed by a full-page advertisement in April, and another nude spread of Kreski in June, which further referenced her acting debut. For middle America, Playboy was the “acceptable view of erotica,” and Merkin was Playboy-approved. In cities like Detroit, Minneapolis, and Louisville, this X-rated musical was a smash.

Moreover, Merkin was not universally derided by critics. Though reviewers generally agreed that the film had flaws, many still admitted that its “moments of eccentric charm and bizarre interest” (Los Angeles Times) made it “somehow . . . a rather enjoyable little something” (Chicago Tribune). And in the end, as both Roger Ebert and Judith Crist acknowledged, Merkin was sort of “critic-proof.” The reflexive premise allows for characters who are screenwriters, producers, and critics—all of whom accuse Merkin’s cinematic project of being self-indulgent, meandering, and tasteless. Those same complaints were lobbed by real-life critics at Newley’s musical, but Merkin itself had already beaten them to the punch.

To my mind, Ebert gets the film just right: even if it’s “not quite successful” in its endeavor to be the nudie musical version of Fellini’s 8½ (1963), it is nevertheless “strange, wonderful, original.” It is, as Variety called it, a “cinematic phantasmagoria.” And it is, as the Los Angeles Times and many others noted, a filmic artifact that defines a generation—the “ultimate statement of the decade of the pink Cadillac, the mink-trimmed john, [and] the topless saloon.” Love it or hate it, Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? is a musical oddity not to be missed.