VAMPIRES IN HAVANA: Gleefully Tawdry Marxism

VAMPIRES IN HAVANA

The following notes on Juan Padrón's 1985 animated horror-comedy Vampires in Havana, were written by Tim Brayton, PhD candidate in UW-Madison’s Department of Communication Arts. A 35mm print from the University of North Carolina School of the Arts will screen in our annual series supported by the UW's Latin American, Caribbean and Iberian Studies program (LACIS) on Friday, February 15 at 7 p.m. The screening, originally scheduled to take place in our regular venue, 4070 Vilas, has been relocated across the street to the Chazen Museum of Art, 750 University Avenue.

By Tim Brayton

There really is no preparing for Vampires in Havana, the third animated feature made by Juan Padrón (the only significant animation director in Cuba at any point during the 1970s and 1980s). It’s easy enough to consider the film’s obviously-impoverished aesthetic, and compare it to the Saturday morning cartoons of Hanna-Barbera or other similarly cash-strapped American studios. For it does resemble such work more than slightly. Or we could look at the music culture that forms the film’s setting, not to mention its non-stop fascination with sex, and see it as a descendant of the urban American underground animation of creative radicals like Ralph Bakshi, director of the notorious X-rated cartoon Fritz the Cat.

But for all that such comparisons might give us a handle on Vampires in Havana as an object, they don’t get us very far. It’s best not to try too hard contextualize this film in American animation at all. This is a Cuban film through and through, starting with its historical setting in the early 1930s, near the end of Gerardo Machado’s tenure as dictator. Despite all of the sex and vampirism that course through the film, the narrative focus remains squarely on Machado’s tyranny and the efforts by an amateur group of revolutionaries to oppose his regime. The radicalism inherent to underground animation is thus politically-oriented in a way that it isn’t always with the American and European films that share the simple aesthetic of Vampires in Havana. Even its status as simply a dirty cartoon, with substantial female nudity and naughty-minded visual gags, is complicated by revolutionary politics: much of the sexual humor in the film hinges on the main character’s dalliances with Machado’s wife.

Of course the more prominent political message in the film derives from its titular monsters. Undying fiends, descended from the European aristocracy, that survive by sucking the very blood out of defenseless working humans? One hardly has to look deep at all to see why vampires are a perfect subject for Latin American Marxist satire. Vampires in Havana goes further than this by positing two different vampire populations: besides the conservative European branch of the species, there’s also a burly, rough-and-tumble American vampire mafia, based in Capone-era Chicago. This narrative positions the Cuban vampire hero Pepito as standing against not just native-born exploitation, but against competing foreign influences trying to dictate his future – exactly the state in which Cuba found itself in the decades before the 1950s revolution.

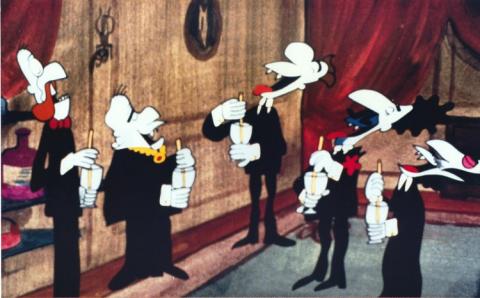

The combination of revolutionary history and silly-looking cartoon characters undoubtedly makes for a baffling viewing experience. During the film’s brief appearance in U.S. theaters in 1987, The New York Times (one of the only outlets to take notice of the film at all) ran a review trying to determine if the “bright colors and brash spirits” on display made this a highly inappropriate film for children, or a highly infantile film for adults, before ambivalently concluding, “the 14- to 16-year-old crowd may not get the anticapitalist message, but they might be tickled by the fangs.” Three decades later, with cartoons for grown-ups having become an established genre, it’s a bit easier to appreciate the film’s goofy approach to serious subject matter. Even so, this is a particularly simplified style, one that’s more The Flintstones than The Simpsons, and the intrusion of sex and violence into such a lighthearted aesthetic remains startling. Impressively, unlike the more openly gritty and grotesque American underground animation of the 1970s, the Saturday morning cartoon cheeriness of Vampires in Havana has allowed it to retain something of the original appeal of underground animation. There is a real sense of the film managing to get away with something subversive here, turning the corny visual gags and caricatured designs typical of children’s cartoons into something hard-edged and more than a little perverse.

This is exactly how it wants to be. Vampires in Havana isn’t trying to be a goofy comedy about wacky animated monsters, nor a mere satire of greedy capitalists and politicians. It is a vigorous celebration of armed revolution. It is unmistakably a propaganda piece, treating Pepito as a slapstick heroic figure: his resistance to Machado is treated as self-evidently admirable even when he comically messes it up, and his defiant act of sticking it to the foreign vampire powers is treated as a giddy, rah-rah climax. The film doesn’t argue for the righteousness of Pepito and his friends, so much as it takes them for granted. In the context of such a straightforward call to mock the bourgeois and their sense of propriety, this dirty vulgar treatment of a kids’ television animation aesthetic is just one more bit of aggressive radicalism. It’s an approach that insists on being snotty and shocking rather than sophisticated and intellectual: in the finest tradition of underground animation around the world, this is first and foremost looking to shock the squares, and doing so with good taste would be almost entirely beside the point. And good taste is certainly something this gleefully tawdry comedy avoids completely.