These notes on of Pedro Almodóvar's The Skin I Live In (La Piel Que Habito, 2011) were written by Tim Brayton, PhD candidate in UW Madison’s Department of Communication Arts. A 35mm print of The Skin I Live In will screen as part of our Sunday Cinematheque at the Chazen series tribute to Almodóvar on Sunday, October 29 at 2 p.m. in the auditorium of the Chazen Museum of Art. Free admission!

By Tim Brayton

Just in time for Halloween, Cinematheque's ongoing series celebrating the work of director Pedro Almodóvar turns to the Spanish master's closest brush with horror cinema. 2011's The Skin I Live In, like any other Almodóvar film, is ultimately too densely packed with a wide variety of styles and narrative ideas to belong in any one genre: questions of gender and sexual identity rub elbows with a melodramatic tale about a bereaved doctor trying to make the synthetic skin that might have saved his unfaithful wife from suicide. It's the usual Almodóvar mixture of absurdity, horniness, and unapologetic grotesquerie, far more than it slots into any conventional category.

But what else are we to make of a film whose story mainly focuses on the demented revenge plot of a genuine mad scientist? Dr. Robert Ledgard (played by Antonio Banderas, reuniting with the director 22 years after Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) is a perfect example of a latter-day Dr. Frankenstein, his desire to make the world a better place through the power of a medical scientist turning into something curdled and perverse as a result of his suffering. Almodóvar himself was quick to notice this in interviews immediately following the film's premiere at Cannes:

"I was most interested in the thrillers of the 1940s of filmmakers like Fritz Lang… but the screenplay did not fit this perfectly. Finally, the only clear reference was George Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or better yet the myth of Prometheus on which it’s based, is a better reference that I noticed only afterwards."

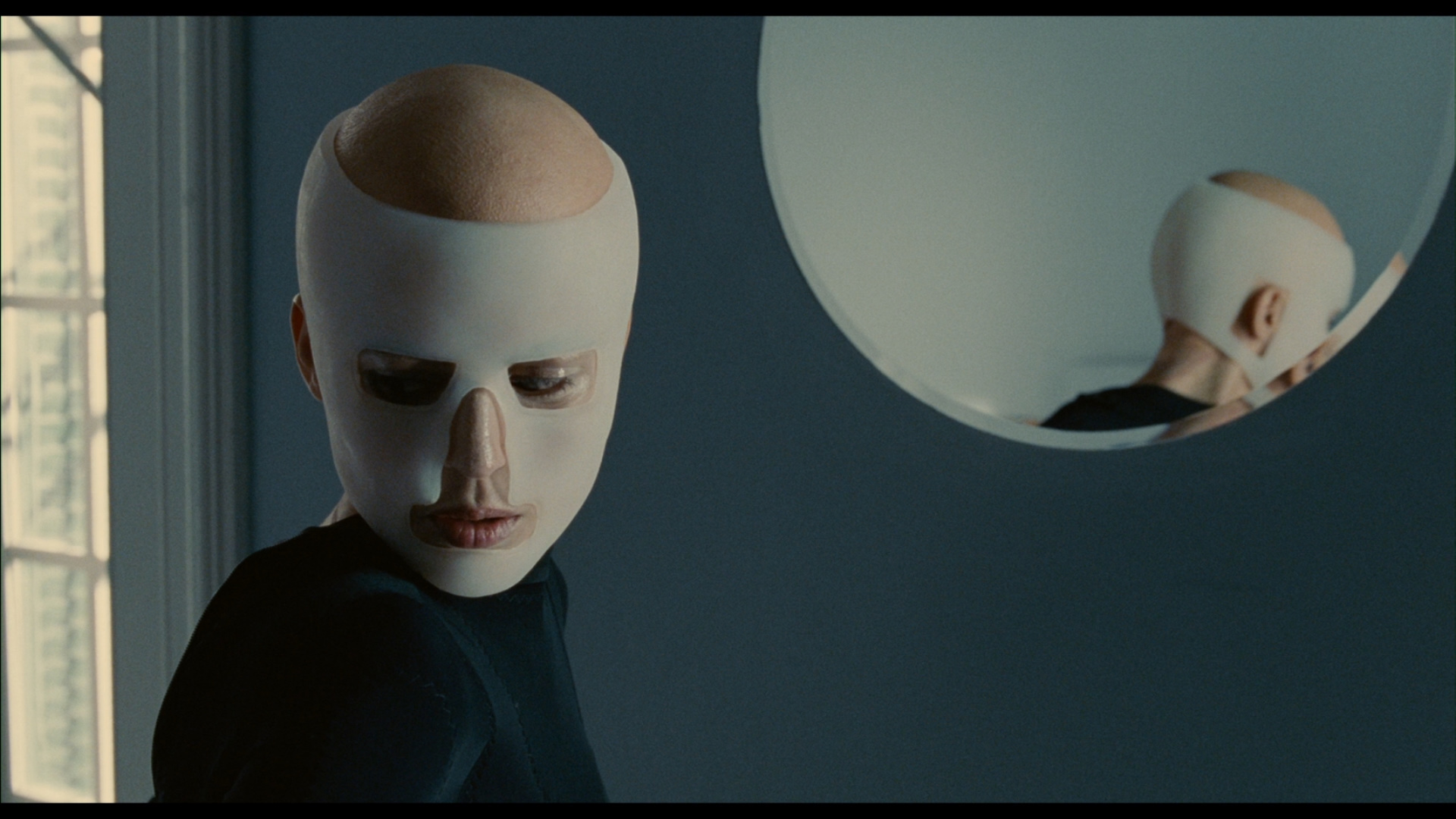

The Franju comparison is obvious from any piece of promotional artwork used around the world to sell the film during its initial release: one of the most striking images in The Skin I Live In is the translucent plastic mask Robert attaches to the face of Vera (Elena Anaya), the chief victim of his mad science, whose face has been replaced with the bad doctor's new synthetic skin. It's an obvious visual reference to the unnaturally smooth, expressionless mask worn by Edith Scob throughout most of Franju's art-horror classic, and certainly the most tasteful, respectable nod to the work of horror films past.

Not that Almodóvar has ever been a filmmaker overly concerned with good taste! The Skin I Live In borrows from substantially less critically-approved sources than Franju's film. The sordid, violent sexuality that underpins everything about the movie (the plot hinges on two separate rapes, and that's saying nothing of Robert's maniacal plan, a sex crime that I'll not spoil except to say that it seems carefully designed to offend the maximum number of people of every political leaning) has more to do with the sleazy thrillers being made across the globe in the 1970s, with a particularly seedy hub of production in the director's own Spain.

In fact, though Almodóvar has never apparently spoken of this connection, The Skin I Live In bears a remarkable number of similarities to 1962's The Awful Dr. Orlof, a rip-off of Eyes Without a Face that's often credited as being Spain's very first horror film. Dr. Orlof was one of the earliest works directed by Jesús Franco, whose critical reputation comes as close as possible to being the exact polar opposite of Almodóvar's: frequently castigated as morally crass and aesthetically incompetent even by the trash cinema fans most likely to make excuses for the prurient grind house fare that was Franco's stock in trade. Still, the unapologetic excess and front-and-center sexuality in Franco's work bears no small similarity to Almodóvar's most extravagantly lurid work, including The Skin I Live In.

Still, while we can position The Skin I Live In as the arthouse successor to the Spanish exploitation films of generations prior, there's no denying how far beyond their model Almodóvar's body horror melodrama goes. Robert is a '50s-style mad scientist, all right, but he's also a quintessential Almodóvar sexually obsessive male, funneling his broken lust into cruelty and control. Vera is an emblem of the fluidity of identity and desire who could fit comfortably in any of the director's most transgressive early films, though the extraordinary black-hearted tawdriness hiding in her backstory would have been extreme even by the standards of Almodovar's '80s films.

The result is one of the director's most aggressively sexual works (it is difficult to find reviews from 2011 that managed to avoid the word "kinky"), though it lacks virtually any of the eroticism that typifies so many of his sunnier, more openly comic efforts. The Skin I Live In isn't without its campy humor, or its self-amusement at the extremes of its scenario, but camp wasn't Almodóvar's main goal. "It promises endless cruelty," he said in that same Cannes interview, and while it's not as bleak as all that, it's certainly impressive how successfully the film takes the gaudiness of something like Dr. Orlof and transforms it into a sober-minded psychological thriller. In the absence of gore or jump scares, The Skin I Live In proves to be a much more effectively adult kind of horror film: one where the source of horror isn't a movie monster, but the nasty, squalid evil of respectable human beings.