UW's Derek Long on THE BIG PARADE

This essay on King Vidor's The Big Parade was written by Derek Long, Graduate Student and Teaching Assistant in the Communication Arts Department at UW Madison. A restored 35mm print of the silent version of The Big Parade, courtesy of George Eastman House, will screen on Saturday, November 15 at 7 p.m. in our regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall. The screening will feature live piano accompaniment by David Drazin.

John Gilbert Goes to the Front, or How Ya Gonna Keep MGM Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen The Big Parade)?

By Derek Long

Along with Ben-Hur (1926), The Big Parade (1925) solidified Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s reputation for highly polished, star-studded, and prestigious productions—a reputation that would last through to the end of the silent era and beyond. Except where Ben-Hur was a success largely in terms of industry prestige and publicity (it wouldn’t actually make a profit for MGM until it was re-released with a synchronous soundtrack in 1931), The Big Parade was a genuine commercial hit. Initially planned as a John Gilbert programmer at a modest budget of $205,000, the film was later expanded for a roadshow release handled by J.J. McCarthy, the entrepreneur-showman who had managed the distribution of The Birth of a Nation (1915), The Covered Wagon (1923), and The Ten Commandments (1923). This setup would eventually yield MGM $3.5 million in distribution profits, as The Big Parade enjoyed exceptionally long runs at theaters like the Grauman’s Egyptian in Hollywood and the Astor on Broadway, where it played for two years. All this for a final negative cost of $382,000—a pittance compared to the nearly $4 million Fred Niblo threw at the screen to make Ben-Hur. As Thomas Schatz argues, The Big Parade exemplified the new approach to studio filmmaking put in place by MGM production head Irving Thalberg, which emphasized a different kind of extravagance—not of production cost per se, but of ensuring the profitability of a film in distribution through audience previews, retakes, and careful editing. Thus, director King Vidor knew that in telling the story of idle rich kid Jim Apperson’s (John Gilbert) decision to head “Over There,” his friendship with working class comrades (Karl Dane and Tom O’Brien), and his subsequent love affair with French farmer’s daughter Melisande (Renée Adorée), The Big Parade would have to be an epic of more intimate and carefully-crafted proportions.

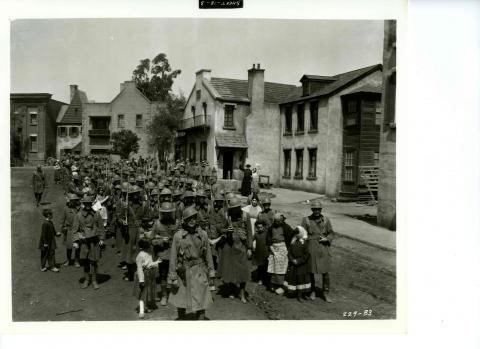

And at least according to his autobiography, Vidor tinkered with The Big Parade considerably in the weeks leading up to its release in November 1925. After audience previews elicited unwanted laughs in a moment where Melisande embraces Jim’s putteed leg, Vidor successively trimmed frames from the shot: “Each night the laugh kept diminishing in volume until it was barely a snicker. After the seventh day of frame elimination, it wasn’t there at all.” When MGM demanded the film be shortened by 800 feet for release, Vidor reportedly cut thousands of individual frames from throughout the film’s thirteen reels rather than excise a single scene in its entirety. Regardless of the truth of either of these anecdotes, Vidor certainly deserves credit for the film’s most famous sequence, wherein Jim’s unit advances toward snipers in the Belleau Wood. Struck by footage of a military funeral procession at the front lines in France, Vidor decided to replicate the cadence of the procession in The Big Parade:

“I was in the realm of my favorite obsession, experimenting with the possibilities of ‘silent music.’ I took a metronome into the projection room and set the tempo to conform with the beat on the screen. When we filmed the march through Belleau Wood in a small forest near Los Angeles, I used the same metronome, and a drummer with a bass drum amplified the metronomic ticks so that all in a range of several hundred yards could hear. I instructed the men that each step must be taken on a drum beat, each turn of the head, lift of a rifle, pull of a trigger, in short every physical move must occur on the beat of the drum. Those extras who were veterans of the A.E.F. [American Expeditionary Forces] and had served time in France thought I had gone completely daft and expressed their ridicule most volubly. One British veteran wanted to know if he were performing in ‘some bloody ballet.’ I did not say so at the time, but that is exactly what it was—a bloody ballet, a ballet of death.”

Apart from Vidor’s direction, much of the credit for The Big Parade’s success lies in its source material, Laurence Stallings’ autobiographical novel Plumes, which had been a huge success in 1924. Stallings, a veteran of the Great War, is probably most famous as the co-writer (with Maxwell Anderson) of the play What Price Glory?, which later received film adaptations by Raoul Walsh in 1926 and John Ford in 1952. Stallings would go on to collaborate with Ford multiple times, on films such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and The Sun Shines Bright (1953). Harry Behn and Vidor expanded Stallings’ initial five-page treatment for The Big Parade into the film’s screenplay, adding the character of Apperson’s mother to make Jim more of a “mama’s boy.” Due credit must also be paid to Joseph Farnham, MGM’s title-writer, as well as playwright Donald Ogden Stewart, whose chance visit to the set while chewing gum inspired the film’s famous love scene between Jim and Melisand

Gilbert’s un-mustachioed Jim Apperson might surprise viewers accustomed to the star’s “Great Lover” image, but The Big Parade made John Gilbert as much as it made MGM. Gilbert had been something of a minor star at Fox before coming to MGM in 1924, but this film made him the biggest male draw of Hollywood’s late silent period (most famously, of course, in his films with Greta Garbo). Renée Adorée never enjoyed quite the same level of fame as Gilbert, though she continued to star in MGM films through the end of the decade. Sadly, her health declined rapidly after that and she died of tuberculosis in 1933.

The Big Parade was not the first 20s epic set during the Great War—Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) had launched Valentino’s career some years earlier, and was actually re-released in 1926 as Vidor’s film smashed records in the big city picture palaces. However, The Big Parade did set off a cycle of Great War films in the latter half of the twenties, including What Price Glory? (1926), Wings (1927), Seventh Heaven (1927), Four Sons (1928), and All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). While these films would often surpass The Big Parade in their stylistic brilliance or the power of their antiwar sentiments, to an extent they could only aspire to Vidor’s intimate depiction of the human costs of the First World War. Of course, they could only aspire to The Big Parade’s box office receipts as well.