This essay on Alfred Hitchcock's Torn Curtain was written by Cinematheque Programmer and Project Assistant Amanda McQueen. A 35mm print of Torn Curtain will screen at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, November 2 at 2 p.m.

Revisiting Torn Curtain

by Amanda McQueen

Torn Curtain was Alfred Hitchcock's 50th film, and many expected that the director would produce something great to mark this seminal moment of his career. Hitchcock had spent most of the 1960s producing psychological thrillers, but given the vogue for spy films ushered in by James Bond, he decided to return to a genre with which he was quite familiar, but that he hadn't tackled in several years. However, Hitchcock didn't want his film to be derivative of the popular Bond series, and so he attempted to make Torn Curtain a different type of spy thriller. Hitchcock explained, "In realizing that James Bond and the imitators of James Bond were more or less making my wild adventure films such as North by Northwest wilder than ever, I felt that I should not try and go one better."

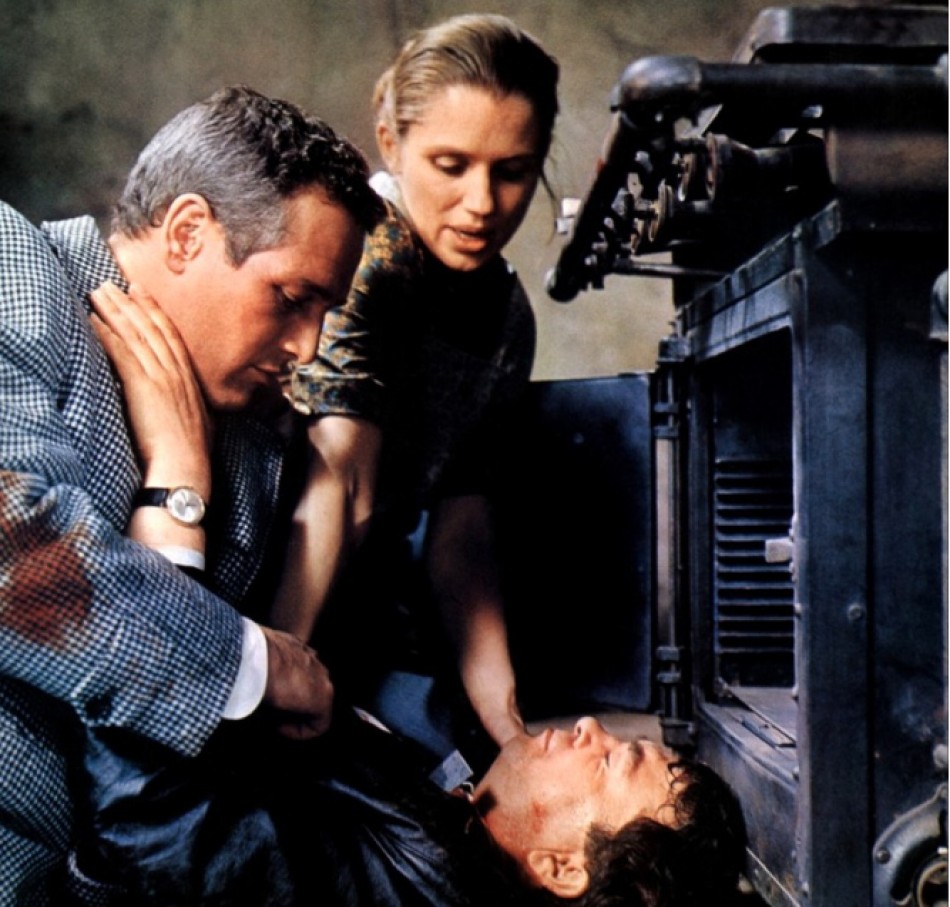

Torn Curtain tells of double agent Michael Armstrong (Paul Newman), a physicist enlisted to gather information about anti-missile technology in East Germany. Unlike Bond, but in keeping with the Hitchcockian tradition of ordinary people pulled into extreme situations, Michael is strictly an amateur spy. And because Hitchcock did not want Torn Curtain to be "a James Bond type 'comic strip' film with its invincible hero and mechanical gimmickry," Michael has no fancy gadgets or special combat skills. This is particularly evident during the film's murder sequence, which takes up nearly five, very tense minutes of screen time, and which certainly proves Hitchcock's point that it is "very difficult, very painful, and it takes a long time to kill a man."

Hitchcock also avoids presenting a straightforward binary between good and evil – such as that between Bond and an enemy organization like SPECTRE. Instead, the director wanted to show that "a spy is a hero in his own country but a villain in enemy country." So Torn Curtain does not have a traditional villain. Instead Michael is pitted against characters that have no openly evil intentions – they just happen to be communists. Some are even quite likable, particularly Hermann Gromek (Wolfgang Kieling), Michael's East German bodyguard, who lets out humorous quips and never operates outside the law. Even though James Bond is often described as an anti-hero, he is still meant to be likable and we are still meant to take pleasure in the skillful way he takes out the bad guys and completes his missions. Torn Curtain, however, asks us to consider how we would respond if roles were reversed and raises the audience's doubt about whether Michael is fully justified in his actions.

Our doubt about Michael is also partially determined by our strong identification with his assistant and fiancée, Sarah Sherman (Julie Andrews). The idea for Torn Curtain came from the true story of British diplomats Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, who spied for and defected to the USSR, but Hitchcock was less interested in the spies themselves than he was in Melinda Maclean, who helped conceal her husband's actions and eventually followed him to the Soviet Union. Torn Curtain thus focuses a great deal of screen time on Sarah's reactions to and participation in Michael's mission, and for the first half of the film, the audience is aligned with her, rather than with our spy hero. Though Sarah proves to be just one of several women who supply Michael with much-needed assistance, she is also the film's moral center.

Hitchcock's attempts to differentiate his film from the Bond series were tempered somewhat by Universal. It was the studio that wanted Hitchcock to hire Paul Newman, in part because he was one of Hollywood's hot new stars, but also because he possessed an athleticism and sex appeal akin to that of Sean Connery (and Newman's body is often on display in Torn Curtain). But where the James Bond connection is perhaps most apparent is in the film's score. The Bond films were known for their soundtracks – for the unique themes written for each installment by John Barry and for their profitable pop songs. Since 1955, Hitchcock's films had been scored by Bernard Herrmann, who was responsible for some of the director's most memorable and lauded soundtracks, including Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960). For Torn Curtain, however, Universal didn't want the same old Herrmann style, and he was instructed to write something more in keeping with contemporary popular music – something that would sell. When Hitchcock rejected Herrmann's attempt, which is structured around repeating and inverted simple scale patterns and unusual juxtapositions between brass and woodwinds, the composer replied, "You don't make pop pictures. What do you want with me? I don't write pop music." Herrmann was fired and replaced by John Addison, who wrote a score built around identifiable themes, or leitmotifs, quite similar to those found in the Bond films.

Torn Curtain was not well received, and comparisons to James Bond were perhaps inevitable. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, for example, complained that "alongside such Bondian adventures as From Russia With Love . . . [Torn Curtain] looks no more novel or sensational than grandma's old knitted shawl." Hitchcock himself was disappointed with the film, and found it interesting only as an experiment with light and color; he relied heavily on natural light and shot through a gray gauze. But the film also displays Hitchcock's continued interest in psychologically complicated characters and manipulation of audience expectations, and the murder sequence is a set piece that holds its own alongside similar moments throughout the director's oeuvre. So even though Torn Curtain is often pushed aside as an aesthetic failure, remembered primarily for breaking up the long-standing Hitchcock/Herrmann collaboration, it has a great deal to offer and is worthwhile viewing for any Hitchcock fan.