The following notes on Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) were written by Lance St. Laurent, the Cinematheque’s Project Assistant and PhD Candidate in the department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A new 4K DCP of Invasion of the Body Snatchers will screen at 7 p.m. on Saturday, February 17, in the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Lance St. Laurent

Jack Finney’s serialized novel The Body Snatchers presents a central premise that has proven resonant across generations, adaptable to different political climates while always appealing to the same fundamental (and fundamentally egocentric) anxiety. What if everyone is out to get me? What if I’m the only real person left? Finney’s novel has inspired four different film adaptations to date, along with countless others that have reworked or ripped off some element of its central premise. 1954’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, directed by low-budget genre specialist Don Siegel, is usually discussed in the context of the Cold War, inviting disparate readings as either a warning against Communist infiltration or as a broadside against McCarthyite groupthink. Abel Ferrara’s 1993 Body Snatchers (written by UW-Madison alums Stuart Gordon and Dennis Paoli) was seen on release as a pointed critique of militarism and conformity in the wake of the America’s first Gulf War. However, it is Philip Kaufman’s second adaptation—1978’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers—that has most managed to transcend its specific cultural and political context to gain broader acceptance as a horror classic.

All four versions of Body Snatchers start with the same premise. Alien, plant-like lifeforms make their way to Earth and begin discreetly duplicating and replacing human beings, leaving their loved ones terrified and unable to explain to onlookers that their seemingly unchanged spouse or sibling is someone, something different than they were before. Kaufman, working with screenwriter W.D. Richter, moves the action from small-town Southern California to San Francisco, taking advantage of the city’s unique weather and landscape along with its (then still recent) associations with the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. For Kaufman, who had relocated from Chicago to San Francisco in the 60s as part of this countercultural wave, moving the setting was a choice with deep, personal meaning. “Could it happen in the city I love the most? The city with the most advanced, progressive therapies, politics and so forth?”

Donald Sutherland stars as Matthew Bennell, a prickly health inspector approached by his colleague Elizabeth (Brooke Adams) about her boyfriend’s unusual behavior. She suspects he may be an imposter, but Matthew approaches the problem rationally, first suggesting that she talk to a local celebrity psychologist (Leonard Nimoy, in terrific form as a smug, shallow intellectual) about her relationship. Matthew is skeptical, despite the warnings of a raving man (Kevin McCarthy, in a cameo nod to the original film) suspiciously pursued by an emotionless mob. Despite the psychologist’s attempts to hand-wave her concerns, Elizabeth finds others with similar stories, and after answering a call to a local spa, the truth is revealed. Elizabeth’s paranoia is founded in fact; an alien force is indeed assimilating unsuspecting citizens of San Francisco. What remains to be seen is whether they can be stopped or if the entire human race is doomed to succumb to a silent invasion.

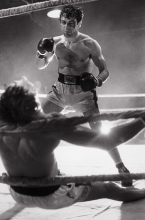

Kaufman looked to the original film’s noir-adjacent black and white cinematography as a starting point for the look of his own film, collaborating with cinematographer Michael Chapman—between his work on Scorsese’s Taxi Driver in 1976 and Raging Bull in 1980—to create an evocative, moody palette and, in Kaufman’s words, “get that film-noirish feeling in color.” Kaufman describes using these expressive lighting and framing techniques to “code” the film and clue the audience in to potential threats. “We would say, ‘What degree of poddiness does this character have?’ And we would put a slight purplish tinge around the gills. We had certain angles that we hoped would sort of indicate a pod creepiness to things.”

Kaufman gave similar attention to the film’s soundtrack. The film’s score, the only film credit from jazz pianist Denny Zeitlin, is a mixture of traditional Hollywood bombast with more experimental, electronically infused compositions, all contributing to the film’s classical, yet modern approach. Sound designer Ben Burtt (fresh off Star Wars) further contributed to the film’s sense of encroaching dread, employing still relatively new Dolby Stereo sound technologies to create a soundscape that shifts through the film, “highlight[ing] strong elements of nature amid bustling humanity in the early stages that give way to a more industrial noise.” The collective effect of these various elements is a remake that pays respect to the spirit of Siegel’s original film (and Finney’s original story) while achieving what Kaufman referred to as “a variation on a theme.”

Invasion of the Body Snatchers opened as the feel-bad event of the Christmas season, December 22, 1978, earning a healthy $25 million (over $100 million adjusted for inflation) in its initial box office run. Critics, too, lauded Kaufman’s remake, particularly Pauline Kael, who called it “the American movie of the year” and “maybe the best movie of its kind ever made.” Its reputation has only grown in stature since, with the film frequently cited as a top-tier blend of two popular subgenres of the era—socially-conscious dystopian sci-fi and post-Watergate conspiracy thrillers. It has also entered the rare canon of horror remakes that match or even exceed their original inspiration, a distinction shared by the likes of John Carpenter’s The Thing and David Cronenberg’s The Fly. Anyone who has seen the film, particularly its unforgettable ending, is likely to understand its storied reputation and continued relevance. Philip Kaufman (now in his late 80s) has spoken about the film extensively in recent years, particularly around the film’s 40th anniversary in 2018, and he has not been shy about what he sees as the film’s appeal in today’s political climate. “I feel that ‘poddiness’ has taken over a lot of our discourse. […] What I like about the film and the original is the subtext that if we go to sleep we could turn into pods. We should not only say our prayers before we go to sleep, but we should examine ourselves upon waking in the morning […] In the end, if the film is valid — which I hope it still is — it’s really the loss of humanity that’s the tragedy.”