THE LUSTY MEN: Never a Cowboy That Couldn't Be Throwed

This essay on Nicholas Ray's The Lusty Men (1952) was written by Jonah Horwitz, Ph.D. candidate in UW Madison's Department of Communication Arts. A recently struck 35mm print of The Lusty Men, courtesy of The Film Foundation and the Academy Film Archive, will screen at 2 p.m. on Sunday, November 1, at the Chazen Museum of Art. This screening is part of the Sunday Cinematheque at the Chazen "35mm Forever!" series.

By Jonah Horwitz

The Lusty Men was made by a dying film studio under chaotic conditions. Having passed through at least seven screenwriters and four titles, it still survives as one of director Nicholas Ray's most graceful and lyrical films—a subtle, melancholic exploration of machismo and its discontents.

The film’s origins go back to a 1946 Life magazine profile of Bob Crosby, "King of the Cowboys" by Claude Stanush. "Wild Horse Bob" was a 26-year veteran and the greatest champion of the North American rodeo circuit. Crosby paid for his "reckless" and "savage" performances with a series of gruesome injuries, leaving his right leg—which he delighted in showing off—"little more than an atrophied shank." At age 49, Crosby was a "paunchy, creaking champion well past his prime," but still competed in as many events as his insurance policy allowed.

Film producer Jerry Wald spotted the Life article, purchased the rights, and charged Stanush with preparing a film on Crosby’s life. He paired the Texan journalist with the more experienced New York novelist David Dotort. Their treatment had mutated by late 1950 into "Cowpoke," a semidocumentary look at the peripatetic milieu of rodeo cowboys, supplemented with a raft of research notes on their folkways: dialect, eating habits, mating rituals, and death drives.

Meanwhile, Wald left Warner Bros. (where he had produced a long series of successful films, including Mildred Pierce, Dark Passage, and Flamingo Road) for RKO. The studio’s new owner, millionaire Howard Hughes, lured Wald and partner Norman Krasna with a promise that they would make 60 films in five and a half years—with full creative control. Wald and Krasna brought with them a shelf of unproduced screenplays, including "Cowpoke."

However, Hughes proved a troublesome studio boss. When he wasn’t meddling in casting decisions, titles, budgets, and ad campaigns, he went incommunicado, taking months to respond to memos and approve scripts. As a result, output at RKO—already troubled before Hughes’s takeover—slowed to a crawl. The hurry-up-and-wait production of The Lusty Men exemplifies this dysfunction. When Hughes finally got around to "Cowpoke," he insisted on a change of title—to "Rough Company"—and that Stanush and Dotort’s discursive treatment be beat into more conventional dramatic shape. For this job Wald sought the services of Horace McCoy, a distinguished novelist (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) and screenwriter (Gentleman Jim) who specialized—per Wald’s secretary’s notes—in "masculine relationships." McCoy borrowed a stock situation, familiar from 1938’s Test Pilot among other films, involving tough men in dangerous occupations: a world-weary former daredevil takes an increasingly cocky upstart under his wing. The former became Jeff McCloud, a down-on-his-luck former champion with a few busted ribs and a yearning for stability; the latter, Wes Merritt, a cowhand whose first taste of the arena proves addicting.

Wald invited Nicholas Ray, a RKO contract director fresh off of the eccentric noir On Dangerous Ground, to helm the film. Within weeks, Ray was travelling with a small crew to the Pendleton Round-Up in Oregon to shoot documentary footage of bull riding, bronco busting, and trick roping. Ray also made crucial casting decisions, hiring Robert Mitchum to play Jeff—winning out over Wald’s concerns that the beefy star would "sleepwalk" through his part—and Arthur Kennedy for Wes.

By November 1951, McCoy had submitted only two-thirds of a script, and things became frantic. Hughes announced another title change—to "This Man Is Mine"—and a major addition to the cast: Susan Hayward, the star of Smash-Up (and invariably described as "tempestuous"), would play Wes’s wife Louise. Hayward would get top billing over Mitchum and Kennedy, and her part—anemic in McCoy’s draft—had to be expanded posthaste, the narrative reshaped from a two-hander into an understated triangle. What’s more, Hayward was on loan from 20th Century-Fox and was available for only a few short weeks before she would be whisked away to Africa to shoot Fox’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro—meaning the film would have to start shooting very soon, with or without a final written act.

Finding himself unwilling or unable to write a convincing female part, McCoy dropped out. (He soon cannibalized his own script for another rodeo film, Universal's Bronco Buster, which was completed and released before RKO had wrapped The Lusty Men.) Wald then corralled a series of experienced screenwriters—Krasna, Niven Busch, Alfred Hayes—to complete the screenplay. New scenes—some of them based on ideas supplied by Ray and Mitchum—were being dictated as late as December 17. Even after filming began, Hayward insisted on rewrites. Wald brought Andrew Solt to the set to touch up her dialogue.

Although in later years Ray would boast that The Lusty Men was largely improvised, there was a full script by the time shooting began, two days after Christmas 1951. Despite being the work of many hands, the story has a thematic coherence that resonated with both Ray and Mitchum. Ray declared that The Lusty Men "is not a Western." Indeed the film takes place long after the closing of the frontier, but its preoccupation with a rugged masculinity—unsettled, risk-taking, competitive—and its opposition between roaming and settling down echoes that of countless period Westerns. What Ray, the cast, and the many screenwriters brought to the archetypal plot and familiar theme was a behavioral nuance and sociological specificity. The dialogue is full of quotable found metaphors and droll aphorisms. Asked if he's "a thinkin' man," McCloud responds, "Oh, I can get in out of the rain."

Like his character, Mitchum was skilled at projecting tough-guy indifference, often protesting to appreciative interviewers that his job was merely one of memorizing lines and hitting marks. He later claimed—as would Kennedy—to have been bewildered by the lengthy discussions of motivation that the Method-trained Ray would indulge in preparing for scenes. But Ray surmised that Mitchum's persona was largely a defense mechanism; he worked closely with Mitchum and brought him to identify with his character, and the project became an unusually personal one for Mitchum. He had spent much of the Depression years wandering himself, and could sympathize with what Ray observed was the "great American search" of the postwar years: "People who want a home of their own." Mitchum's performance—possibly his best—is distinguished by delicate shades of dissimulation and guarded revelation. His Jeff wears the easy confidence of a proven champ and lothario, and his first passes at Hayward’s Louise are thoughtless, almost reflexive. But unlike the eager Wes, Jeff is all too aware of the hazards of his profession. His inchoate longings for a place to rest—the film begins with him returning to the homestead of his childhood, a scene restaged in Wim Wenders's 1976 Kings of the Road—gradually find expression in a desire for Wes’s wife, a desire born of empathy. Louise, the child of migrant farm workers, picked Wes as her best hope for a stable home life precisely for those qualities—modesty of ambition, consistency of character—that his shot at rodeo glory has tempted him to betray. Jeff will ultimately sacrifice himself to see this hope restored.

Unlike Mitchum, Hayward didn’t warm to Ray’s cryptic ministrations, feeling excluded from the conspiratorial rapport between co-star and director. It’s possible that something of that annoyance inflected her portrayal of Louise, who spends much of the film rolling her eyes and lashing out at the two man-children she is stuck with. Hayward’s star persona was of a driven woman calamitously undone by undependable men; here, the men remain undependable, but Louise has a self-possession that allows, for once, a measured triumph.

Hayward shot most of her scenes on studio lots in California, and when her loan period was up, Ray and his male stars went on the move, shooting at a number of rodeos: Tucson, San Angelo, Pendleton again. Mitchum and Kennedy insisted on riding bulls themselves, and these shots were later intermingled with the documentary footage made in the fall. Filming completed just before Valentine’s Day 1952. Wald was uncertain of the downbeat ending, and offered Ray a bonus to shoot a new, happier—but entirely implausible—one in April. The film was privately screened with this new ending, and everyone except Wald was duly chagrined; the producer eventually relented. But even after Ray and editor Ralph Dawson had finished a cut of the film, Hughes dithered, largely because he no longer liked the title he had chosen back in November. Handed a list of alternatives, he circled "The Lusty Men" and finally approved the film for release.

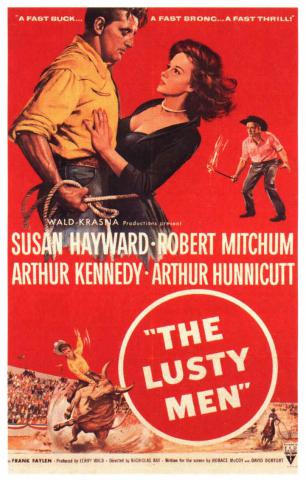

The Lusty Men made it to theaters in October 1952. It was given unusually wide distribution for the era, opening simultaneously in numerous cities and abetted by an innovative national television advertising campaign. Critics were very kind but box office was modest. The posters and trailers—not to mention the title—promised an action spectacle that the film didn't deliver. In France, where Ray had been gathering a reputation as a maverick auteur, it received a rapturous review by Jacques Rivette in Cahiers du cinéma. Rivette praised Ray’s "search for a certain breadth of modern gesture and an anxiety about life, a perpetual disquiet that is paralleled in the characters; and . . . his taste for paroxysm, which imparts something of the feverish and impermanent to the most tranquil of moments."

And RKO? The same month that The Lusty Men was released, Wald and Krasna parted ways with the studio, having made only five films in two years—many fewer than anyone had anticipated. Hughes was forced out of RKO around the same time. Production at the studio was temporarily halted as the new owners sought to make emergency repairs to the studio’s leaking hull. It didn’t take; RKO released its last picture in 1957, leaving behind a legacy of many glorious films, The Lusty Men not the least among them.