The following notes on Killer of Sheep were written by Mattie Jacobs, PhD candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW – Madison. A new 4K restoration of Killer of Sheep will screen at the Cinematheque on Friday, November 21. Showtime is 7 p.m. at 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Mattie Jacobs

For three decades, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep stood as the legendary lost classic of Black American Cinema, languishing without distribution due to a complex entanglement of rights issues. The saga of Killer of Sheep begins and (almost) ends with the soundtrack. Burnett’s tapestry of Black life in the Watts neighborhood is underscored by Earth, Wind, and Fire, Paul Robeson’s renditions of “My Curly Headed Baby,” and, in the film’s most beautiful sequence, a quiet and intimate dance to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” But the musical weight of this debut film unfortunately kept it locked out of distribution, tied to the licensing rights of each song. The music is integral to the Black community shown on the screen, a community that Burnett had set out to document while working on his Master of Fine Arts at UCLA. He was, as he suggests, an outsider-insider, trying to show life on screen as it was really being lived.

Watts is obviously central to the film, an essential element not only to the visual landscape, but to the people themselves. Burnett noted in interviews his desire to showcase the life of the Watts neighborhood that he lived in at the time, exploring how the community was still centered around older members who had experienced “the worst episodes of discrimination and survived.” “Their attitudes and how these people carried themselves” was at the center of the film, Burnett acknowledged, with the film standing as his effort to “give these people their due.” The intensity of the social bonds and the self-possession of the neighborhood is visible, even as its poverty is manifested clearly. As presented by Burnett, life in Watts is both beautiful and despairing, with these contrasting registers signifying the lifeblood of the community. Paul Robeson’s “The House I Live In”—another rights problem for Burnett—plays repeatedly throughout the film as we see these collections of homes, all shot with an eye towards finding the beautiful lived-in nature of the environment. In doing so, Burnett enlivens a community that others would so often find on the news, framed as run-down and pitifully poor.

In this, Burnett follows in the tradition of the chroniclers of American poverty and locality, most strongly from James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Praising Agee and Evans, Burnett notes how he tried to emulate their approach to documenting these places they came to as outsiders, seeking to capture something—and in that capturing becoming part of this space. He notes that “the whole idea behind it was to make a film about how some people in the black community really lived without imposing my values on it.” The film presents these moments of life strung together in almost unconnected vignettes. Stan (Henry G. Sanders), a slaughterhouse worker, attempts to provide for his wife and family, initially getting wrapped up in an assassination plot—that his wife curtails immediately. Later, a flirtatious white woman tries to give him a new job in exchange for favors; in another sequence, we see a heartbreaking, backbreaking attempt to haul an engine across town.

Los Angeles is also central to Burnett. A key member of the movement that would come to be known as the L.A. Rebellion, a collection of filmmakers born out of that UCLA film program, Burnett worked alongside directors like Julie Dash, Larry Clark, and Haile Gerima, even taking on the role of cinematographer on the latter’s 1979 Bush Mama. The group found inspiration in Italian neorealist films and cinematic movements of resistance from South America (such as Cinema Novo), but the Rebellion also existed in Los Angeles in the large shadow of Hollywood production and distribution. Though it shows the influence of neorealist cinema from Rossellini and de Sica, Killer of Sheep is, for Burnett, more of a reaction to Hollywood. The film is his response to both the Blaxploitation films of the period—especially Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971)—as well as more mainstream pictures like Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree (1969). In his words, he found himself trying to thread the needle between these two predecessors, presenting Black life without stylized violence while also pushing further towards “realism” than Parks or Sidney Poitier could manage in Hollywood.

Shot on the weekends for two years, Burnett submitted the film after five years as his Master of Fine Arts thesis. And there it existed in cans as Burnett finished the final edit, subsequently failing to find any distribution that would deal with the complex music rights. Though the UCLA Film & Television archive did restore and enlarge the 16mm film to a 35mm print, the film was only available around the country at festivals and cinema clubs for decades, winning awards and praise for Burnett wherever it went—a masterpiece you had to catch when you could. Not until 2007 did Killer of Sheep find wider distribution through the efforts of Milestone Films, who have now produced this 4K restoration.

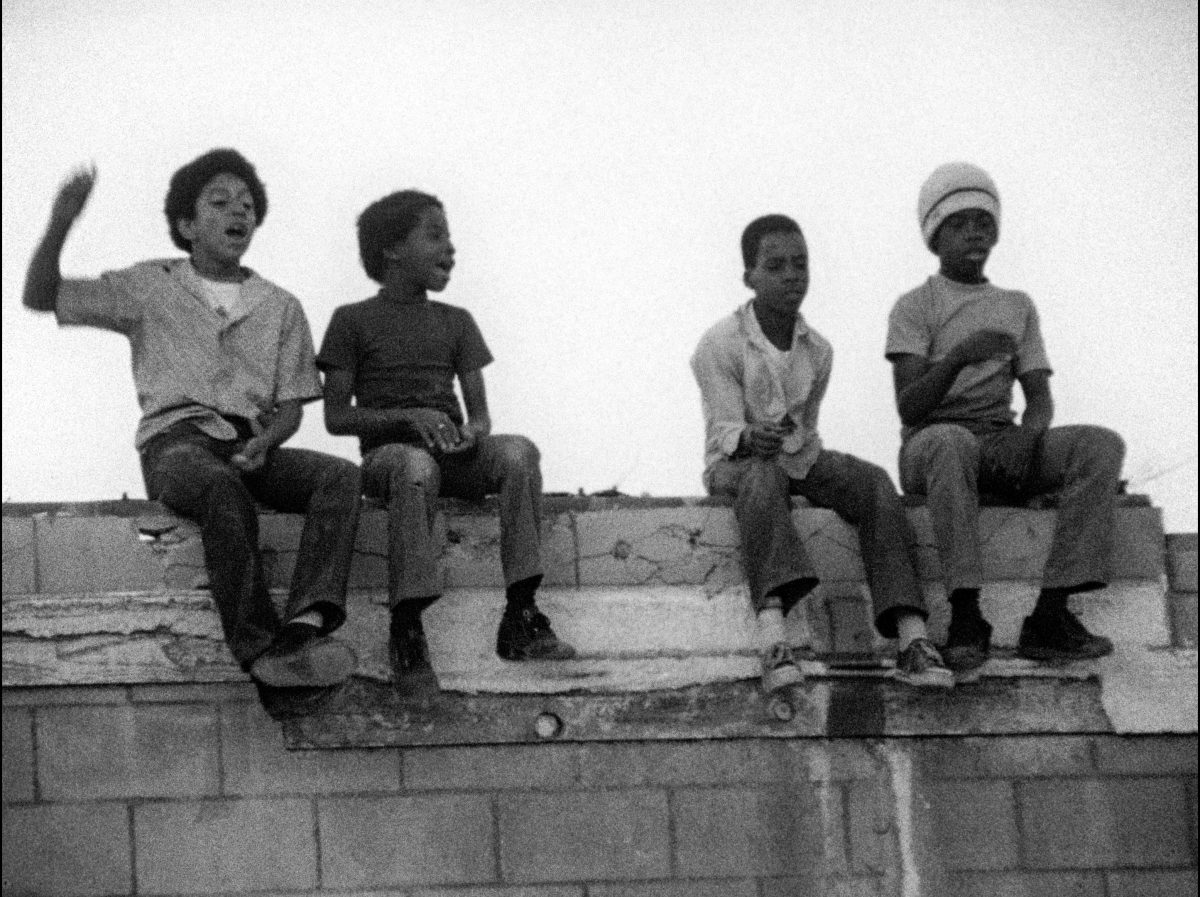

The film’s images still produce awe. Burnett often frames around vertical lines, showing doorways—or closely built buildings and fences—looking into and out of the houses and apartments in Watts. Friends and neighbors enter and hug through these doorway frames, bringing warmth and life into kitchens and living rooms. Stan plays with his children, drinks coffee all hours of his insomniac nights, and dances with his wife (Kaycee Moore) in front of a glowing window, his home some refuge from the world continually trying to wear him down. His children run through Watts with the rest of the neighborhood kids, playing in abandoned alleys and empty lots. In one sequence, which I believe was inspired by the photographs of Eugene Meatyard, the daughter wears a dog mask around, covering her face as she listens to adult conversations. Stan’s depression, exacerbated by the psychological toil of poverty, his slaughterhouse job, and the world that seems oriented against him, deeply wears on his face. Sanders, himself a Vietnam Vet now enrolled in acting school, brings every ounce of the weight of the world to Stan, conveying every trial and sleepless night, every failed scheme, each moment of discrimination. But Stan continues on, the distance between himself and the world much like the distance between two people dancing to “This Bitter Earth,” their bodies pushed together before coming apart again.