The following notes on Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse were written by Sarah Mae Fleming, PhD candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW – Madison. A 35mm print of Pulse screens at the Cinematheque on Friday, October 3, 7 p.m., in the Cinematheque’s regular screening space, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave. Admission is free!

By Sarah Mae Fleming

Kiyoshi Kurosawa once joked that Japanese ghosts “don’t do anything.” Indeed, in Pulse (2001), Kurosawa’s ghosts move slowly, never shriek, and hardly seem to care about those they are haunting. That blank passivity makes them a startling image of death: always present, impossible to reason with, and indifferent to whether we notice it or not. Pulse swaps gory spectacle for slow-burn dread, finding terror not in monstrosity, but in the loneliness of the hyper-connected modern world. The film begins with a spate of suicides seemingly connected to the internet, yet in contrast to what you might expect from a Western horror picture, no one steps into the role of the investigator. There are no determined heroes consulting civil authorities or piecing together a grand conspiracy with red yarn. The focus slides unnervingly from victim to victim, one by one, until the remaining characters, Michi (Kumiko Asō) and Ryosuke (Haruhiko Kato) realize the world is dying—only to find that the world is already dead.

Unlike so many horror films, Pulse refuses to populate its story with recognizable archetypes. There is no “final girl,” no reckless partier, no skeptic who insists nothing unusual is happening until it’s too late. The characters are students, office workers, technicians—ordinary people leading unremarkable lives in unremarkable spaces. The absence of these archetypes unsettles the genre’s usual rhythms and expectations. In American horror movies, we often watch to see who will survive and who will be punished; the tension derives from recognizable patterns of behavior and consequence. In Pulse, no one is especially virtuous, nor is anyone especially culpable. People disappear at random, with no explanation and no possibility of intervention. The effect is not catharsis but aimless drift, like the film itself is being pulled into the same atmosphere of dissolution that overtakes its characters.

Kurosawa has remarked on this difference in cultural expectations. When presenting his work abroad, he noted that American audiences often pressed him with questions: What is the character’s intent here? What is their goal? His response was straightforward: sometimes the character has no goal at all. His characters are “just existing,” Kurosawa explained. The result is a horror film in which characters don’t propel the story so much as meander through it, already ghostlike, solitary, and waiting for their quiet disappearance. Narrative, genre, and atmosphere all bend around that central absence of motive. By stripping away the archetypes and ambitions that usually drive horror forward, Kurosawa creates a world that feels inexorably stalled, suspended between life and death.

The path from Pulse’s Cannes premiere to US screens was equally circuitous. It was marked by delays, corporate maneuvering, and an English-language remake that drew more attention to Kurosawa’s version, even as it paled in comparison. Dimension and Miramax initially acquired the film after its premiere to distribute in the US, yet the Weinstein Company then purchased the rights to the film in a bid to shelve it so they could produce their own Hollywood remake. In the meantime, Pulse went on the festival circuit, rarely shown to US audiences until Magnolia Pictures obtained the rights in 2005. Shortly after, the Wes Craven-produced remake of Pulse (Sonzero, 2006) was released to a fair box office performance and harsh reviews. In Variety, Robert Koehler described the remake as a “dumbed-down” take that stripped away Kurosawa’s patient dread in favor of a flat, literal approach to the story.

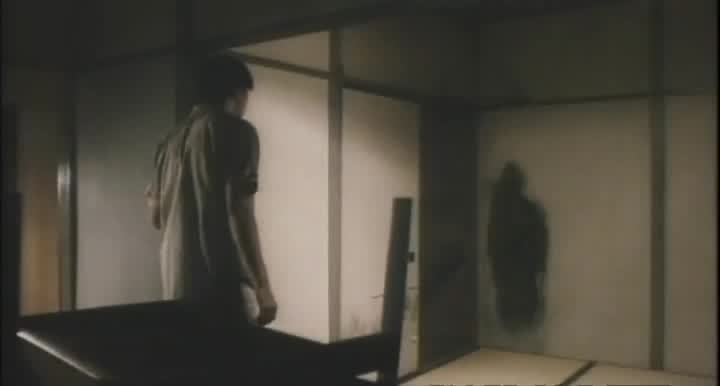

Kurosawa had some hesitations about translating his film for US audiences, remarking upon his anxiety about interpreting Japanese sensibilities in the Hollywood system. In contrast to what American viewers expect from movie monsters, Japanese ghosts, according to Kurosawa, don’t do much aside from impressing upon the living their deadness. Kurosawa’s ghosts stand apart not just from American horror, but also the longer tradition of Japanese horror conventions. His ghosts are not quite the long-haired “dead wet girl” ghouls of other J-horror hits, nor do they sport Kabuki whiteface in a kaidan tradition. They appear as ordinary, albeit unsettlingly slow and languid, human figures. The horrifying, awful closeness of death is what distinguishes Kurosawa’s ghost story, forcing the human characters to continue the routine of daily life even in the presence of encroaching death.

If character and plot provide the film’s structural challenge to convention, sound and space provide much of its affective power. Kurosawa is a filmmaker interested in sonic environments. He employs far less music and far more effects, often amplifying real-world sounds, like the rustling of leaves, the squeak of a chair, or even the buzzing of an insect. He seldom resorts to digital sounds, relying instead on the subtle modulations of physical materials at his disposal. One of Kurosawa’s major interests as a filmmaker is how to portray the world beyond the frame. The buzzes, low-pitched drones, and hisses are not random; they are meant to be the sounds that emanate from next door, from behind the walls, and across the street. The sound design becomes a breach, a window through which the incomprehensible forces on the other side enter the characters’ world.

Though set in the most physically crowded places on earth, Pulse creates a city that appears to be occupied by a dozen people. Kurosawa prefers to shoot in deserted, even decaying, locations: rooms that are too large, streets that are empty, and abandoned buildings that feel unnervingly vast. To augment this, Kurosawa often films his characters from a distance. By maintaining this gap, we as viewers are made acutely aware of the periphery—the shadows in the background, and the lingering and persistent presence of the dead. Pulse’s horror is not in a jump scare, but in the slow realization that we are surrounded by a wider, terrifying reality that we have failed to perceive.

The end of the world is rarely silent on screen. A Hollywood apocalypse is typically rife with explosions, screams, and dramatic last stands. The vehicle for Kurosawa’s quiet annihilation is the internet, a superhighway to connection that only accelerates isolation. The ghosts don’t really do anything that we have not already done to ourselves.