Evan Davis on Orson Welles's TOUCH OF EVIL

This essay discusses Orson Welles's TOUCH OF EVIL and was written by UW Alum and former Cinematheque staff member Evan Davis. TOUCH OF EVIL screens in a 35mm print of the 1998 "memo cut" restoration in the Cinematheque's regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, on Saturday, February 28 at 7 p.m.

By Evan Davis

We finally arrive at the concluding miasma that was Orson Welles’s long relationship with Hollywood, the culmination of the film noir movement as it has been understood up to now, with the noir form stretched as far and as grotesquely as it could go: Touch of Evil (1958). Perhaps more studied and analyzed than any other Welles film besides Citizen Kane (1941), this nasty little tale of police corruption and border town crime has been thoroughly canonized. But that fate wasn’t always guaranteed.

By now, the story is approaching tired cliché: Welles goes to work for a minor studio, leaves or is tossed off the lot, and then the studio re-cuts, re-writes, and re-shoots behind his back. Everyone goes back and forth as to whether Welles was self-indulgent, slow, wasteful, and didn’t care about protecting his own work, or if he was maligned by the suits who only cared about the bottom line. The case of Touch of Evil is no different. What is different is what came after.

Welles shot Touch of Evil in the spring of 1957. In July of that year, he left the editing room (whether by choice or by mandate is unclear). Meanwhile, Universal hired Harry Keller to direct some additional scenes to be included in the film. Welles saw a rough cut that autumn, and wrote a 58-page memo that December, detailing all the changes he wanted Universal’s team to make. A small number were implemented, but most were ignored. The studio released a 93-minute edit in early 1958. In 1976, a 108-minute cut initially used as a preview version made it into circulation, with several more minutes of Welles’s footage included. It also contained a great deal more of Keller’s re-shot material. And so the preview version and release version were the only things people could judge Touch of Evil on for 40 years.

You may recall: the studio destroyed the cut footage from The Magnificent Ambersons; if the excised material from The Stranger and The Lady from Shanghai exists, then no one’s turned it up. Welles’s Hollywood career is woefully incomplete. Universal Studios, however, hung onto the sloughed-off images and sounds of Touch of Evil, and in 1997, a project began that was to do for that film what couldn’t be done for so many earlier ones. Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum—who originally published the memo in 1992—producer Rick Schmidlin, and legendary editor Walter Murch set about instituting every single editing request Welles made in the memo. They had to keep some of the Keller footage for reasons of continuity, but once they premiered the film at Cannes in 1998, the world finally had as close a “Welles version” as they were ever likely to get. It may not be a director’s cut per sé (who knows what Welles would have done had he been allowed to complete the editing himself), but it’s still an incredible reconstruction.

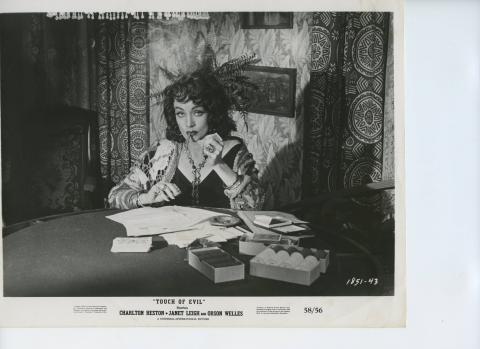

What’s most impressive about it is the subtle shifts in rhythm and tone. At 111 minutes, it’s the longest version of the film—only about five or six minutes are completely new. But Murch and his team incorporated Welles’s rigorous cross-cutting methods to depict up to four different plotlines simultaneously unfolding. They also changed the soundtrack to emphasize Quinlan’s (Welles) brutality in order to make him less sympathetic. (Note Quinlan’s offscreen beating of Sanchez [Victor Millan] while Mike Vargas [Charlton Heston] searches Sanchez’s apartment.) Lines that more explicitly describe the Grandi gang’s plan to frame Susan Vargas (Janet Leigh) for heroin use are added. All of this is per Welles’s instruction. And of course, the greatest coup is the opening tracking shot, with Henry Mancini’s score removed, the credits deleted, and the “radio-dial” atmospherics of sound added, sounds emanating through the town while Mike and Susan stroll to the border.

Touch of Evil brought back the long, sinewy mobile takes of Welles’s initial Hollywood period, coupled with a thoroughly contemporary representation of the seedy side of life on the US-Mexican border. It is scabrously funny and also tender and mournful. It is full of bravura and also of nuance and subtlety. It is, in other words, an Orson Welles film. (It also contains the last great performance by Marlene Dietrich.) It is undoubtedly one of Welles’s best, and we are pleased to present this reconstruction in glorious 35mm.