Feed Your Head: Michelangelo Antonioni’s ZABRISKIE POINT

ZABRISKIE POINT

These notes on Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point were written by Will Quade, PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication Arts at UW Madison. A 35mm print of Zabriskie Point will screen on Friday, October 12 in our regular screening venue, 4070 Vilas Hall. This screening is presented with the support of the Center for European Studies, in conjunction with a Saturday, October 13 workshop entitled “Tracing the Impacts and Representations of 1968."

By Will Quade

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960s output made him the preeminent scholar of modern alienation, but the beginning of Zabriskie Point strikes one as immediately different from his previous explorations. The camera darts from face to face in violent swish pans and close-ups as an eerie patter of drums and whispered vocals (Pink Floyd’s “Heart Beat, Pig Meat”) fill the soundtrack but then are soon replaced by a cacophony of passionate, earnest young voices. Above the noise, real life Black Panther leader Kathleen Cleaver attempts to inform and organize a politically radical group of mostly white students. We are privy to snippets of speeches and grand questions (“What if you want to abolish sociology?”) but are frequently lost spatially in this cramped room as we scramble to hold on to something consistent amid the mess of raised hands and erratic volume. Slowly we are shown a slouching young man three times, our soon-to-be protagonist Mark (Mark Frechette), eyes glazed over at the incessant speechifying. Soon, he finally stands up to the group, announcing, “Well I’m willing to die too… But not of boredom.”

It’s quite clear from this statement and fly-on-the-wall opening that it is Antonioni himself who feels distanced among the most politically active participants of his new world. Along with other directors such as John Boorman and Jacques Demy, Antonioni was one of a cadre of European filmmakers to be given unprecedented freedom by a major studio (MGM) and used this to come to the west coast. After his commercial and critical smash Blow-Up (1966), Antonioni took his newfound countercultural status and bankability to Los Angeles to document the rising student rebellions happening in 1968. But unlike his polished and highly manicured first English language film, Zabriskie Point is rough, raw, and perfectly willing to embody the confusion and half-formed ideas of his two young leads.

Besides Mark, the film follows Daria (Daria Halprin), a flower child willing to secretary for some bread. Along the way her sometimes-boss Lee (Rod Taylor) becomes smitten and invites her to a real estate development in Phoenix. Contrasting with the crowded telephoto framings of Mark’s student meeting and subsequent riot and jail footage, Daria’s office building is photographed in the trademark cavernous lobbies and sharply defined offices of Antonioni’s previous films. As an enormous American flag billows quietly behind Lee’s upscale workstation, there’s nary a single diagonal to add any kind of further dimension to its image. In Antonioni’s most striking deletion of depth, Lee’s secretary is seen scrunched in the right fourth of the frame as she takes a message, seemingly crushed by an accordion-like wall that threatens to push her out of existence.

It doesn’t take long to see where Antonioni’s sympathies lay. Mark is forced to flee unfeeling authorities as we follow him from a violent encounter with police at a county jail to a murderous student demonstration. But beyond the cops that assault Mark, the sheer signage of the Los Angeles cityscape represents another type of oppression. Consistently dwarfed by ads for 7UP, airlines, or foodstuffs, Antonioni forces us to ride shotgun in filmed car rides spying on billboards, signposts, and painted advertising murals in all their gargantuan horror. It’s little wonder that Mark’s means of escape from the law and the America he so despises is to steal a small plane and ride joyfully above the cramped, commodified city set to Grateful Dead’s victorious “Dark Star”.

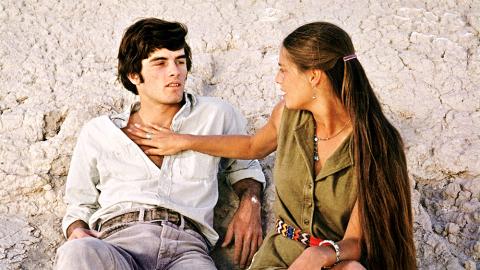

But after this midway point, Antonioni shifts his focus to the real estate firm Daria works for; here another altogether more sinister villain. We are forced to watch in quickly cut extreme close-ups a commercial for a future desert suburban paradise Lee is bankrolling posed entirely with dolls and models. If Los Angeles served as a current source of shameless capitalistic parasitism and political rut, the rape of the land and expansion of these literally hollow ideals prove to be the most insidious arms of American exploitation. In contrast, Daria and Mark flirt in the Arizona desert, fall in love, and begin a childlike tryst in the desolate Zabriskie Point, culminating in a playful, dusty orgy of young people (most of whom were members of Joseph Chaikin’s experimental Open Theater troupe). While Daria’s superiors would believe this land is empty and ripe for development, and Mark claims flatly, “It’s dead,” Antonioni and Daria view it with boundless life — even her proposed “killing game” is in fact an ever-growing list of all the living creatures inhabiting the severe landscape. In her eyes, the desert’s epic vistas are filled with scores of gyrating, exuberant lovers, presenting more of a utopian idyll than a freak sex romp. But it is exactly this type of innocence which cannot possibly last back in the real world.

With Antonioni fully investing us in Daria’s heart and mind, it’s only fitting that she guide us to the film’s shattering conclusion. Positioned precariously between the worlds of violent political protest and callous big business, we are implicated in her final choice and revelation. A suitably thundering finale provides an indoctrination of sorts that aligns the viewer completely with her experience. Amidst Pink Floyd’s narcotizing soft-loud “Come in Number 51 (Your Time Is Up)” and lengthened climactic imagery, what begins as pure metaphor soon evolves into something akin to the Star Gate sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey. A galactic hole is ripped open in Daria’s mind and by the end we have been transformed — we have evolved. Antonioni is no longer merely observing and reporting with an outsider’s suspicion. He has distilled in us a true insurgent spirit. In each viewer, a new revolutionary is born.